Why The Bank Of Canada’s Rate Hikes Are Not Working

Image Source: Pexels

After a year of steady interest rate hikes, the Bank of Canada continues to warn that rates are going to remain “higher for longer”, a mantra that seems to dominate monetary authorities everywhere. Despite the bank rate hitting a 22-year high of 5% this month, there seems to be a lessening fear that credit restrictions will lead to a recession. Given the Bank of Canada’s bias in favor of a recession over continued inflation above the 2% target, it is no wonder the Bank threatens to continue to raise rates should there be a whiff of higher inflation. The Canadian economy continues to expand, albeit slowly, and shows no signs that rate hikes have worked their supposed magic in bringing inflation in line with long-term targets. True, the CPI has dropped dramatically from 8% in January to 2.8% last month, but the Bank officials remain very weary of a renewal of cost pressures at any moment.

So, after doing everything, including throwing in the kitchen sink (quantitative tightening) at the inflation problem, the Bank of Canada is having less of an impact on consumer spending and borrowing than their economic models projected.

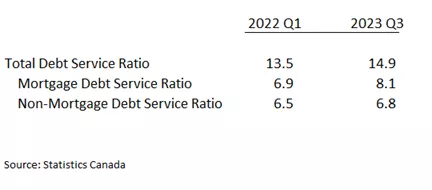

The accompanying table separates the two basic components of consumer debt: mortgage and non-mortgage debt. Pre-pandemic, 15% of household income went to service debt, which is still higher than the 14% experienced today, despite interest rates moving up by 400 basic points in the same period. Put differently, Canadians have a smaller debt servicing load today than they experienced when the bank rate was near-zero. Why is this so?

To begin with, nominal incomes have increased by just over 6% this past 12 months, allowing consumers to absorb much of the increases in borrowing costs. A combination of paying down debt, especially during the pandemic lockdowns, and higher incomes since have lessened the interest rate burden.

Debt Servicing Cost Ratios, Canada

The bulk of mortgages in Canada mortgage rates are fixed, commonly for a 5-yr term. Mortgage debt interest is priced off the longer-term government bond yields. These yields have not risen as fast as the bank rate and their influence has kept fixed rates lower than otherwise expected. Estimates provided by the mortgage industry indicate that approximately 15% of all fixed-rate mortgages over the next year come up for renewal this year. Thus, we can expect a small increase in the overall debt service ratio. Meanwhile, the bulk of remaining fixed-rate mortgages carry a very low rate. Depending on how long-term bond yields move over the next 2 years, the majority of mortgage borrowers will continue to experience relatively low-interest rates. On top of that, many banks are offering borrowers the opportunity to extend their amortization terms from 25 years to 30 years which helps greatly with monthly cash flows.

The question of how high will fixed mortgage rates go depends entirely on the outlook for the 5yr bond yield. Economists expect the 5 yr bond yield, currently sitting at 4% to fall to 2.5%, reducing the pressure on those renewing in the next two years or later. Finally, as the table reveals, the debt servicing costs for non-mortgage loans have barely moved this past year, as consumer credit rates have not followed the surge in the bank rate.

So, the credit markets have not yet made any real impact on consumer debt servicing, challenging the Bank of Canada rate hike policies. Ironically, as the Bank raises short-term rates, the yield curve inverts further, resulting in a suppression of fixed-rate mortgage rates in the future, encouraging yet lower borrowing costs and higher asset prices.

More By This Author:

The Bank Of Canada Has Entered The Realm Of OverkillCentral Bankers Are No Longer So Self-Assured

Canada Needs To Promote Business Capital Investment If It Hopes To Tame Inflation

Disclosure: None.