Canada Needs To Promote Business Capital Investment If It Hopes To Tame Inflation

Image Source: Pexels

It is now been two years since the Bank of Canada started its relentless policy of raising interest rates in its battle against inflation. Every rate hike is supported by a narrative that the growth in consumption---- goods and services—needs to be reigned in. Take the most recent rate hike announcement in which the Bank points to the “surprisingly strong” consumption in goods and services This surprise resulted in the Bank abandoning its recent decision to pause and opening the door to additional rate hikes.

However, the use of one blunt policy tool--- interest rates—has the unintended consequences of dampening business investment and its derivative productivity growth. In its policy review documents, the Bank acknowledges that business investment has been very sluggish. Yet it does not make the connection that business capital formation is one of the most interest-sensitive sectors and that raising rates retard the growth in the capital stock. Business capital formation is best understood as the addition to plant and equipment, including software in the private sector. Within the public sector, capital formation includes transportation networks, electrical supply, and other infrastructure. Collectively, the higher the capital formation, the faster an economy can grow and, above all else, the greater improvements in productivity, the source of enhanced national wealth.

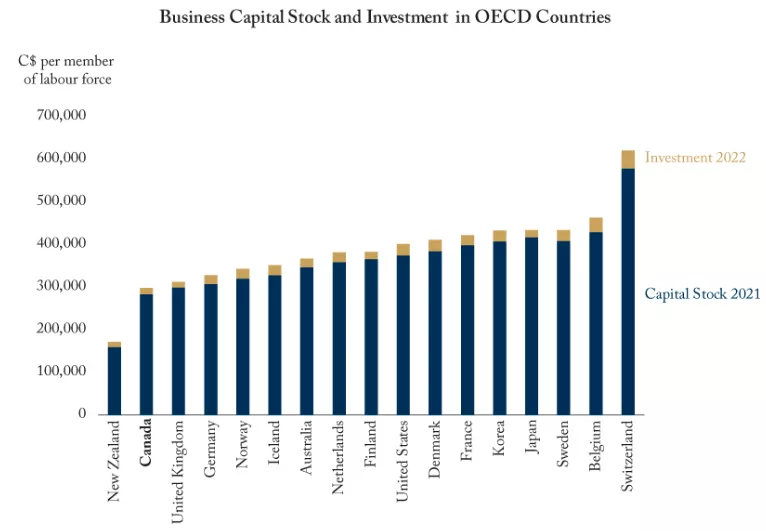

The C.D. Howe Institute made it abundantly clear that business investment in Canada is one of the worse in the OECD. Canada’s capital stock per potential worker in 2021 was the second-worst among the countries with comparable data. Canadian capital per worker stood at $283,000, only three-quarters of the US level. The OECD anticipates that additional capital invested per worker in 2022 will be just $14,800 in Canada, only about half the US tally. What is more startlingly is that Institute claims that

“Canadian firms are either unaware or unconcerned about the opportunities and threats that would prompt them to undertake productivity-enhancing investment projects. Canadian governments should use tax, regulatory and trade policies to enhance the rewards for investment and the penalties for falling behind. Canadian workers need better tools to enhance their productivity, their earnings, and their competitiveness” (investment weakness).

(Click on image to enlarge)

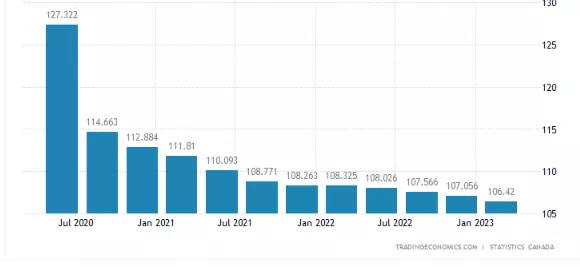

So, back to the Bank of Canada and its inflation-fighting strategy. The accompanying chart documents the steady decline in labour productivity.

Canadian Index of Labour Productivity

Put aside the abnormal period during the height of the pandemic, the level of output per worker has steadily declined, quarter after quarter, in the short span of 2 years. This is a period where the Canadian economy was supposed to be expanding. GDP growth appears to driven by population expansion, not be enhanced productivity. Declining productivity has a direct correlation to increasing unit labour costs and that, in turn, generates rising consumer prices. In an earlier blog (anti-growth), it was argued that the Bank of Canada seems to adopting an anti-growth philosophy and this is no more evident than by its indifference to the consequences of rate hikes on capital formation and overall worker productivity.

More By This Author:

The Bank Of Canada Continues To Struggle With Timing Its Policy Changes

Canadian Banks Signal The Coming Economic Downturn

Why Central Banks Forecasts Totally Missed The Surge In Inflation

Disclosure: None.