Thoughts For Thursday: What Kind Of A Week Is This?

Nothing severe is happening in the market this week, but nothing seems to be running smooth either. There is a lot of geopolitical noise coming from the Middle East and China which is contributing a fair amount of uncertainty, without mentioning the Iowa caucuses or the upcoming New Hampshire primary.

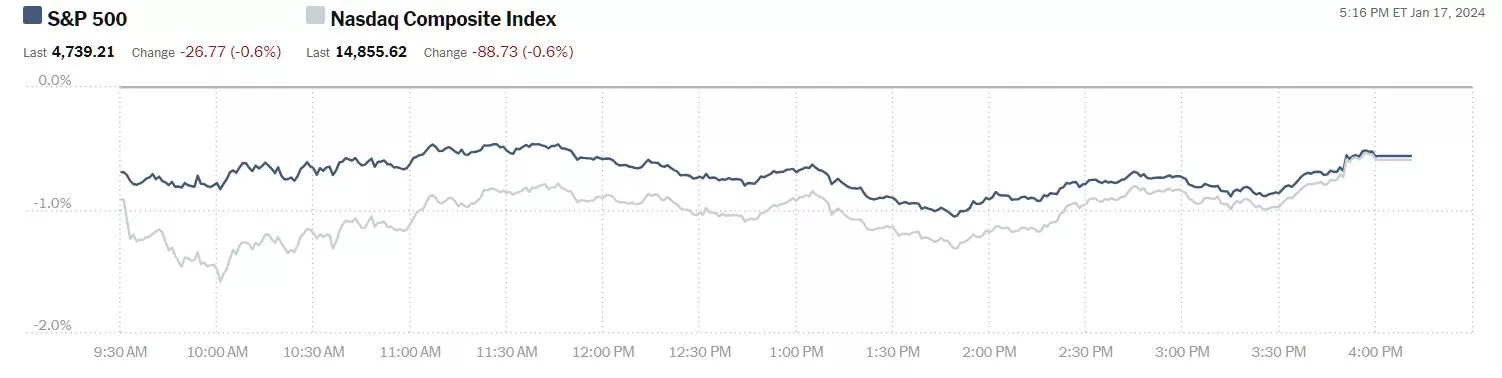

Wednesday the S&P 500 closed at 4,739 down 27 points, the Dow closed at 37,267, down 94 points and the Nasdaq Composite closed at 14,856, down 89 points.

Chart: The New York Times

Most actives were led by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), up 0.9%, followed by Tesla (TSLA), down 2% and Ford (F), down 1.7%.

Chart: The New York Times

In morning futures action S&P 500 market futures are up 17 points, Dow market futures are down 6 points, and Nasdaq 100 market futures are up 119 points.

Talk Markets contributor Gail Tverberg in an Editor's Choice column writes for 2024: Too Many Things Going Wrong .

"Economies, in physics terms, are similar to human beings. Both are dissipative structures. They require energy of the appropriate kinds to keep their systems growing and operating normally. For humans, the main source of this energy is food. For an economy, it is a mixture of energy that the economy is specifically adapted to. Today’s economy requires a certain mixture of energy directly from the sun, plus energy from fossil fuels, burned biomass, and nuclear energy. Electricity is a carrier of energy from different sources. It needs to be available at the right time of day and the right time of year to allow today’s economy to continue...

Trying to predict precisely what will happen in the year 2024 is difficult, but in this post, I will examine some of the things that are going wrong in this increasingly creaky old economy.

[1] Too many parts of the world economy are changing from growth to shrinkage.

The blue circles can illustrate many different things:

- The total goods and services produced by the economy;

- The quantity of energy required to produce the total goods and services produced by the economy;

- The total population that is supported by these goods and services (which will generally be rising or falling, too);

- Goods and services per person (which tend to rise during periods of growth and fall in a shrinking economy);

- And, strangely enough, the ability of the economy to maintain complexity. Without enough energy, structures such as governments tend to fail.

As the economy moves away from growth, toward shrinkage, major changes can be expected.

[2] In a growing economy, repaying debt with interest is very easy. In a shrinking economy, repaying debt with interest becomes close to impossible.

If an economy is growing, there will likely be an increasing number of jobs available over time, and they will pay relatively more. If a person loses his/her job, it is not very difficult to get a position that will pay as much or more. Paying back a loan on a house or an automobile tends to be easy.

A corresponding situation occurs for businesses. If the business can count on an increasing number of customers, the overhead becomes easier and easier to cover with a growing consumer base.

The reverse is obviously true in a shrinking economy. Jobs may be available if a person loses his/her current job, but the jobs don’t pay very well. Businesses may face periods with suddenly lower demand, as in 2020. There is a sudden need to reduce overhead, such as payments for office space, if the space is no longer being utilized by employees.

Clearly, if interest rates rise, it becomes increasingly difficult for borrowers of all kinds to repay debt with interest. Raising interest rates is thus a way to intentionally slow the economy. If the economy is growing too quickly (like a 20-year-old sprinter), then such a change makes sense. But if the economy is behaving like an 80-year-old, hobbling along on a walking stick, it becomes likely the economy will figuratively fall and become severely injured. This is the danger of raising interest rates when the world economy is having difficulty growing at an adequate rate.

[3] The physics of the system dictates that as the system shifts in the direction of shrinkage, the wealth of the system is increasingly distributed toward the rich and very powerful, and away from those of modest means.

Physicist Francois Roddier writes about this issue in his book, The Thermodynamics of Evolution. He likens energy (and the goods and services produced using this energy) as being like energy applied to water. When energy levels are low, the less wealthy members of the economy tend to be squeezed out, just as (low energy) frozen water turns to ice. The reduced amount of energy available (and goods and services produced using this energy) increasingly bubbles up to the small number of economic participants at the top of the economic hierarchy. This issue tends to make the already rich even richer.

In some sense, the self-organizing economy seems to preserve as much of the economy as it can, when energy supplies are inadequate. The wealthy seem to be important for keeping the whole system operating, so physics tends to favor them.

Inflation, in general, is a problem, especially for people with limited income. Higher interest rates also take a big “bite” out of spendable income. This problem is greatest for low income people. The benefit of higher interest rates, and of capital gains, tend to go to high income people.

High food prices especially affect the poor because, even in good times, food tends to be a high share of their income. For example, in a poor country, if food costs amount to 50% of a person’s income when food prices are moderate, a 20% increase in food prices will lead to food prices costing 60% of income. Such a situation quickly becomes intolerable because there is not enough income left for other essential goods.

Figure 2. Chart by the Federal Reserve of St. Louis showing the Share of the Total Net Worth Held by the Top 1% of US Citizens (99th to 100th percentile).

The figure above shows that between 1990 and 2022, the share of total wealth held by the top 1% of US citizens rose from 23% to 32%. This means that other citizens were increasingly squeezed out of the benefits of the growing economy.

[4] With their newfound power (arising from the growing concentration of wealth), the wealthy are tempted to exert increasing control over the economic system.

The fact that the world economy was likely to reach annual limits of fossil fuel extraction about now has been known for a very long time. I have referred to a 1957 speech by US Navy Admiral Hyman Rickover pointing out this bottleneck many times. Wealthy individuals have known about this bottleneck for a very long time. They have been asking themselves, “How can we increasingly benefit from this change?”

Clearly, reducing the population growth rate has been one of the goals of some of these wealthy individuals. With fewer people to share the resources available, everyone will benefit.

But the wealthy can also see that hiding the energy bottleneck would be of huge benefit in keeping the current system operating as usual. These individuals, through the World Economic Forum and other organizations, have pushed for zero global warming emissions. They have tried to reframe the problem of inadequate inexpensive-to-produce fossil fuels as a problem of too large a quantity of fossil fuels for the system to handle. In their view, we can decide to transition away from fossil fuels without significant adverse impacts.

By hiding the energy bottleneck, companies selling vehicles can claim they will be useful for many years. Educational systems can claim that we are well on our way to finding substitutes for fossil fuels and that there will be good jobs available in the new systems. With the bottleneck problem hidden, politicians do not have to present citizens with a very concerning and intractable issue. Since a happily-ever-after narrative is desired by all, it is easy for the wealthy (and politicians who want to be reelected) to influence the major news outlets to present only this view to readers.

[5] Major cracks in the economy are likely to start showing soon. The energy bottleneck is already pulling the economy down, even if major news media are reluctant to discuss the problem.

The problem displays itself in several different ways:

(a) The economy has moved toward two widely differing views regarding today’s energy situation.

The narrative presented in the press is that we have an excessive amount of fossil fuels. In this view, any shortage of fossil fuels (or any other resource) would be quickly accompanied by rising prices. These rising prices would allow an increasing quantity of these materials to be extracted, quickly solving the problem. But the real story, for anyone who examines the details, is quite different. Affordability becomes very important, holding prices down. History shows that nearly every civilization has collapsed. Populations tend to grow but the resources supporting the economies don’t grow quickly enough. Rising prices don’t fix the problem!

People who work with fossil fuels know how essential they are for our current civilization. The story about intermittent wind and solar substituting for fossil fuels sounds very far-fetched if a person thinks about the need for heat in the winter and the difficulties associated with the long-term storage of electricity. The two widely differing narratives surrounding our energy future sound like they could have come from the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell.

(b) Repaying debt with interest gets to be an increasing problem.

Strange as it may seem, added debt can temporarily act as a placeholder for additional energy. Debt is a promise for goods and services that will be made with future energy. This placeholder can allow capital goods, such as factories, to be made which allows more goods and services to be made in the future. This placeholder can also be used as the basis for money to pay workers so that they can afford to purchase more goods.

At some point, the debt becomes too much for the system to sustain. We are seeing some of this in China, where there have been debt defaults in the real estate market. In the US, the commercial real estate market is experiencing high vacancy rates. There is increasing concern that, in many places, commercial real estate can only be sold at a huge loss. In this situation, the holders of debt are likely to sustain massive losses.

(c) Political parties start differing widely on whether to increase government debt.

The more conservative parties do not want to keep adding more debt, but the more liberal parties insist that there is no other way out: If there isn’t enough energy of the right kind, the added debt can perhaps be used to fund projects in the renewable energy sector that will create the illusion of progress toward an adequate supply of energy of the right kind at the right price. The added debt can also be used to continue the many social programs promised to citizens and to provide support for activities such as the war in Ukraine.

So far, adding debt has worked for the US because the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency and because the US has tended to keep its target interest rates high, encouraging other countries to invest in US securities. If other countries try to add substantially more debt, their currencies will tend to fall, leading to inflation.

The US may soon also run into an inflation problem because of added debt. This happens because it is possible to “print money,” but it is not possible to print goods and services made with inexpensive energy products. For example, the temptation is to bail out failing banks and pension plans with added debt. To the extent that this debt gets back into the money supply, but there aren’t added goods to match, the result is likely to be inflation in the prices of the goods and services that are available.

(d) Broken supply lines are another sign of an economy reaching limits.

When there aren’t quite enough goods and services to go around, some would-be buyers of goods have to be left out.

In the last three years, all of us have experienced at least some problems with empty shelves in stores and the unavailability of needed parts for repairs. Many kinds of drugs are in short supply around the world. Heavy industry has been encountering problems, as well. In 2022, Upstream Online wrote, “Drill pipe shortages causing headaches for US producers [of oil and natural gas].”

If we are reaching the limit of inexpensive fossil fuel available for extraction, an increasing number of these problems can be expected. These supply line problems tend to raise costs in a different way than “regular” inflation. Often, a more expensive product must be substituted, or a higher cost workaround is needed. For example, a person may need to use a rental vehicle while his current vehicle is being repaired because of unavailable replacement parts.

(e) Conflicts arise when there are not enough goods and services to go around.

Part of the conflict comes from wage and wealth disparity. For example, an increasing number of people are finding reasonably-priced housing impossible to find. The combination of high interest rates and high housing prices tends to make home-buying a luxury, available only to the rich. An increasing share of young people are also finding automobiles too expensive to afford. One way “not-enough-goods-and-services-to-go-around” manifests itself is by many people not being able to afford the products in question.

There is often a belief that a more equitable distribution of income would solve the problem. But, if the economy cannot build more cars or homes because of energy shortages, this doesn’t fix the problem. Providing more money to the poor would instead cause inflation in the price of the goods that are available.

Another way this conflict manifests itself is in conflicts among countries. Countries selling fossil fuels, such as Russia, would like higher fossil fuel prices, so that the standards of living of their own people can be higher. However, if fossil-fuel-importing countries, such as those in Europe, are forced to pay higher prices for the fossil fuel they use, it becomes difficult for companies in these countries to manufacture goods profitably. Also, the higher fossil fuel prices make the cost of growing food higher. Customers often cannot afford higher food prices.

In the case of the fight between Israel and Gaza, at least part of the conflict relates to the natural gas field that Israel is developing, but which arguably belongs to Gaza. If Israel can develop this resource, it may be able to keep its own economy expanding for a while longer. The people of Gaza will remain very poor.

(f) Manufacturing around the world seems to be reducing in quantity. It definitely is not rising to keep up with population growth.

The big shortfall today is in goods, rather than in services. This is what a person would expect if an energy problem is giving rise to the problems we are currently experiencing.

The organization S&P Global Market Intelligence puts out an index called the Purchasing Managers Index, for 15 countries, including a global average. The manufacturing portion of this index is in contraction on a worldwide basis, as of the latest data available. The extent of this manufacturing contraction is especially significant for the US, the European countries included, Japan, and Australia. The countries that are not in contraction are India, Russia, and China.

If manufacturing is in contraction, we would expect more broken supply lines in the months and years ahead.

[6] How will all this turn out, in 2024 and long term?

I don’t think we know. Things are likely to get worse economically, but we don’t know how much worse. We know that an elderly person can easily succumb to some illness. In the same way, we know that if the economy has enough weak points, a major collapse might occur, even without a huge decline in energy availability.

At the same time, the economy seems to have a lot of resilience. Leaders of the US, and perhaps of other countries, as well, seem likely to take the route of adding increasing amounts of debt, to bail themselves out of whatever problems arise. If banks get into trouble, some new funding facility will be developed. If Social Security or private pensions need more funding, it will likely be provided by more government debt. This leads me to suspect that in the US, at least, there is likely to be a higher risk of hyperinflation (lots of money but very little to buy) rather than deflation (very little money, but also very little to buy)...

See the full article for additional commentary.

Contributor Andrew Zatlin says interest rate cuts (This) Could Boost The Housing Market, Stock Market, And U.S. Economy - All At Once

"Welcome back to our look at why 2024 is set to be a banner year in the stock market.

So far, I’ve detailed the upcoming election, and the fact that the economy is in better shape than the “experts” would have you believe. Both of those elements will play a major role in the stock market’s performance this year.

Now it’s time to look at the third reason I’m convinced the market will deliver double-digit returns…

...That reason relates to interest rates — more specifically, interest-rate cuts.

You’ve probably heard a lot of chatter about pending interest-rate cuts. And I’d wager they’re coming down the pipeline...

If you’re an investor, you have a few choices when it comes to where to put your money. For example:

- You can put it into a money-market account, most of which are still paying out around 5% interest.

- You can put it into the stock market, which has historically returned about 8% a year (though it’s been annoyingly volatile the past few years).

- Or you could hand your money off to a private equity fund and hope the fund can deliver on its promise of double-digit returns.

During times of economic uncertainty like we’ve been in, the option most investors have gone with is the money-market account — a virtually zero-risk way to keep your money and earn solid returns. In fact, last year, a trillion dollars flowed into money-market funds.

But that’s about to change. Not only are interest rates expected to stop climbing, but they’re expected to drop in 2024. And as those rates drop, so will the interest offered through investments like money-market accounts.

That means more investors will be flocking back to the stock market and trying to capture the higher returns the market has historically doled out...

Housing represents one-third of our nation’s economy. And as interest rates drop, so will mortgage rates. That’ll make buying a home more affordable (at least somewhat) and will jolt the economy.

But the effects of the jolt won’t stop there. As housing becomes more affordable, more buyers will turn to sectors like furniture, appliances, and electronics. Simply put, the economy is about to experience a major boost when interest rates fall, led by a surging housing market...

2023 was a terrible year for private equity and M&A deals. The value of private-equity deals dropped 55%, while the value of M&A activity dropped 41%. Total capital spending in these areas went from around $4 trillion in 2019 to $3 trillion last year.

A key reason we saw such a drop was that high-interest rates meant that borrowing costs for a deal outweighed any potential value. But with lower interest rates, suddenly those borrowing costs will start to fall, and that’ll send M&A and private-equity deals surging. That missing trillion dollars could be back into play..."

TM contributor Dennis Miller says The Problem Ain’t The Cost Of Money – It’s The Cost Of Stuff.

"...The current Federal Funds rate is 5.5%. Many cheap loans are now coming due and must be paid off or rolled over at a much higher rate.

Prices have exploded!

The Wall Street Journal recently reported the average monthly mortgage payment has soared to $3,322 from $1,787 since 2021. Why?

Interest rates were kept artificially low, and mortgage rates have risen since the Fed brought interest rates back to pre-2008 normal.

MSN.com explains:

“Homeownership has become a pipe dream for more Americans, even those who could afford to buy just a few years ago.

Many would-be buyers were already feeling stretched thin by home prices that shot quickly higher in the pandemic, but at least mortgage rates were low. Now that they are high, many people are just giving up.

…. Typically, high mortgage rates slow down home sales, and home prices should soften as a result. Not this time. Home sales are certainly falling, but prices are still rising—there just aren’t enough homes to go around. The national median existing-home price rose to about $392,000 in October, the highest ever for that month in data that goes back to 1999.

…. Buyers get a lot less home for their dollar. Before the Fed started raising rates, a person with a monthly housing budget of $2,000 could have bought a home valued at more than $400,000. Today, that same buyer would need to find a home valued at $295,000 or less.”

The casino banks are screaming, profits are down, and the Fed has to pivot and drop interest rates. Baloney! When Volcker pivoted, interest rates were double-digits and he pivoted back down to “normal.” Today’s rates are at historical “normal” – what worked for decades.

Lending cheap money to high credit risks (government included) creates the illusion of prosperity while creating terrible, inevitable inflationary consequences.

The cost of money ain’t the problem, it is the cost of stuff.

Leave rates alone, don’t make things worse. Chairman Volcker got us through a recession – things will work out once the excess debt is out of the system.

As always, politicians scream, “Vote for me, I’ll fix the problem!” Ain’t gonna happen, no matter who wins the election. Without massive spending cuts and sanity in Washington, nothing will change. It’s no wonder many of us are holding on to our gold wishing for, “the good old days”..."

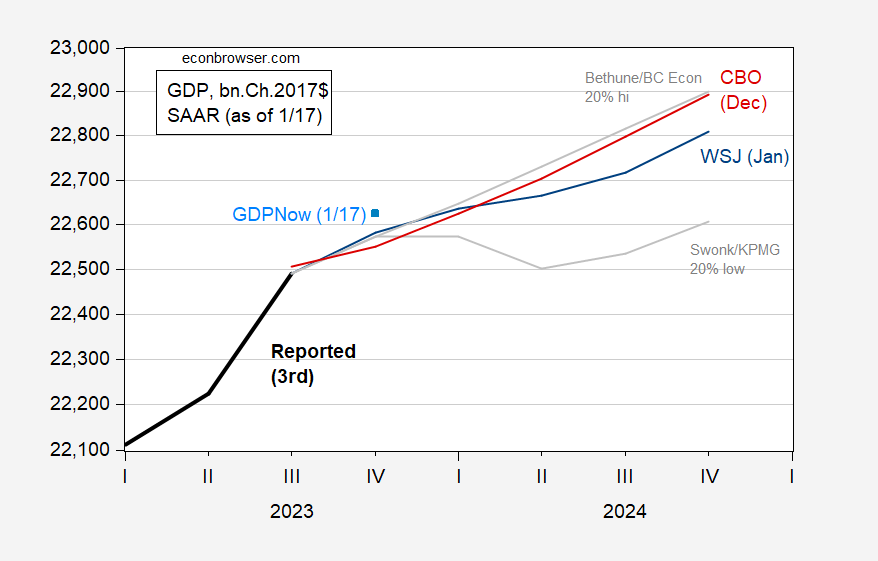

Economist and contributor Menzie Chinn examines the GDP Trajectory: The View From Wall Street.

"The mean forecast trajectory keeps on rising as actual GDP outcomes keep on surprising on the upside (Q4 mean growth rose from 0.9% to 1.7% q/q AR since October), but forecasts are pretty dispersed, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: GDP (black), Mean forecast GDP from January 2024 WSJ survey (blue), 20% trimmed high (for 2023 q4/q4) of Bethune/Boston College Economics. (gray), trimmed low of Swonk/KPMB (gray), CBO projection from December (red), GDPNow nowcast of 1/17 (light blue square), all in bn. Ch.2017$ SAAR. Source: BEA, WSJ surveys (various), CBO, and author’s calculations.

Neither mean nor median responses indicate a two-quarter slowdown. Nonetheless, the 20% band low entry (for q4/q4 2024) from Diane Swonk (KPMG) indicates a 0% growth in Q1, and -1.30% q/q AR in Q2. About 22% of respondents predict two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth.

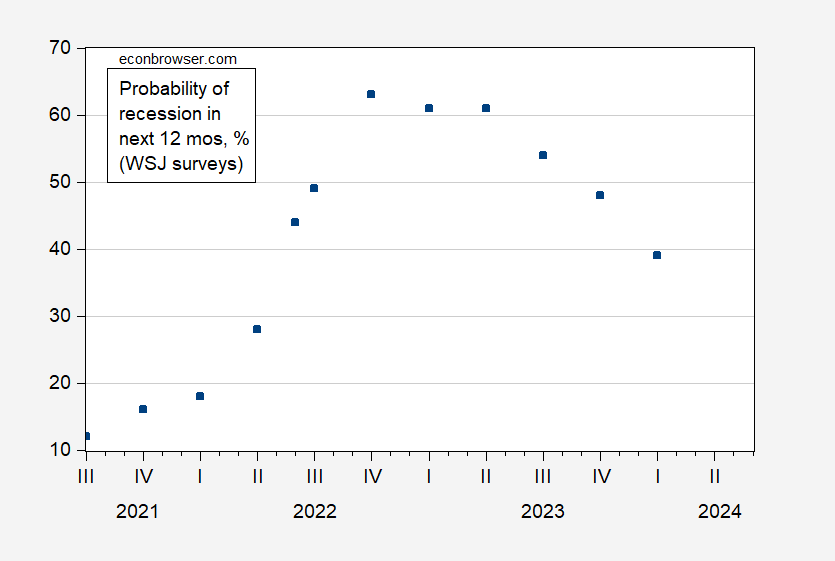

Recession probability declines again.

Figure 2: Probability of recession in the next twelve months. Source: WSJ survey, various issues."

Probability of recession declining over the next 12 months, I'll take it.

Closing out the column today, in the "Where to Invest" Department contributor Tim Fries notes IBM Stock Is At A Multi-Year High, Can Its AI Business Push It Higher?

Image courtesy of 123rf.com

"Over the last three months, IBM stock gained 20% value, reaching the highest price point since March 2017. In the three months, IBM outpaced MSFT at 20% vs. 16%, respectively, although Microsoft has 4x greater gains on a one-year scale.

Will 2024 be the year when IBM finally joins the Nvidia/Microsoft AI party?...

Overall, IBM’s earnings per share of $2.20 represents a 22% growth from a year-ago quarter.

For the full fiscal year, IBM expects up to 5% revenue growth with a free cash flow of ~$10.5 billion, which is $1 billion YoY more. This important metric tells investors that IBM has ample room to reinvest while paying debt obligations and dividends to shareholders...

IBM’s dividend yield to shareholders is 3.98%, delivering an annual payout of $6.64 per share. Microsoft has a dividend yield of 0.77% at a $3 per share annual payout. Based on 13 analyst inputs pulled by Nasdaq, IBM stock is a “buy.”

The average IBM price target is $157.7 vs the current $167. The high estimate is $180, while the low forecast is $120. "

The full article includes additional analysis of IBM's AI strategy.

As always, Caveat Emptor.

Here's hoping the market ends on an upbeat this week.

Peace.

More By This Author:

Tuesday Talk: Walking Back From The Holiday

Tuesday Talk: Magnificent Monday?

Thoughts For Thursday: A Bumpy Ride At The New Year