Weekly Market Pulse: Don’t Be A Newton

Photo by Jason Briscoe on Unsplash

A few weeks ago I asked the question that everyone is asking today: Is This A Bubble? My answer, as it is for most questions about the future, is that I don’t know. But there are some things I do know:

- The S&P 500 is priced for low future returns, quite possibly negative on a real basis over the next 10 years.

- The S&P 500 is very concentrated with 40% of the index in the top 10 stocks and 30% in the top 5

- The S&P 500 is concentrated on a sector basis with over 35% of the index in the technology sector.

- The Nasdaq (QQQ) trades for 27 times forward earnings and the S&P 500 growth index for 28 – and that’s after a 5% correction.

When I wrote that note on November 2nd, the index was very overbought, trading at about 2.5 standard deviations above the 50 month moving average. In a bull market, the index has, in the past, traded at about 2 standard deviations above the average. Corrections, in time or price or both, tend to happen when the index nears 3 standard deviations above. Other technical measures, like RSI, were also in very overbought territory. The index was obviously due for a correction and we’ve had a small one since then and we may very well be in for more.

Most of the comments I received from that commentary didn’t question whether we were indeed in a bubble; that seems to be consensus, with the only question being when one should fade it (sell). Can you have a bubble when “everyone” already believes we’re in one? The answer seems to be no if you believe that markets are efficient and incorporate all known information. In that case, knowledge that the market is drastically overvalued should lead rational investors to sell and bring the bubbly market to heel.

Of course, if investors were always rational the bubble would never inflate to begin with so maybe markets aren’t all that efficient. I certainly don’t think so. I invested through the dot com mania in the late 90s and “everyone” knew we were in a bubble then too. Yes, there were still some cheerleaders at the end but the index overvaluation was so extreme it was impossible to deny. And “everyone” back then was doing exactly what they’re doing today – trying to ride the bubble as long as possible, assuming they’d know when to sell. For what it’s worth, most people back then didn’t.

The most common question I get is what exactly one could or should do when the market is this overvalued. And that’s where the comparison with 1999/2000 becomes very interesting. I have the benefit of having lived and invested through more than my fair share of speculative, overvalued markets. If you were an investor in 2000, you probably hadn’t ever experienced a “bubble” or whatever you want to call it. But I’ve lived and traded through at least 4, including today. So, what do you do in these situations where the market – or at least the index that supposedly represents it – is obviously overvalued?

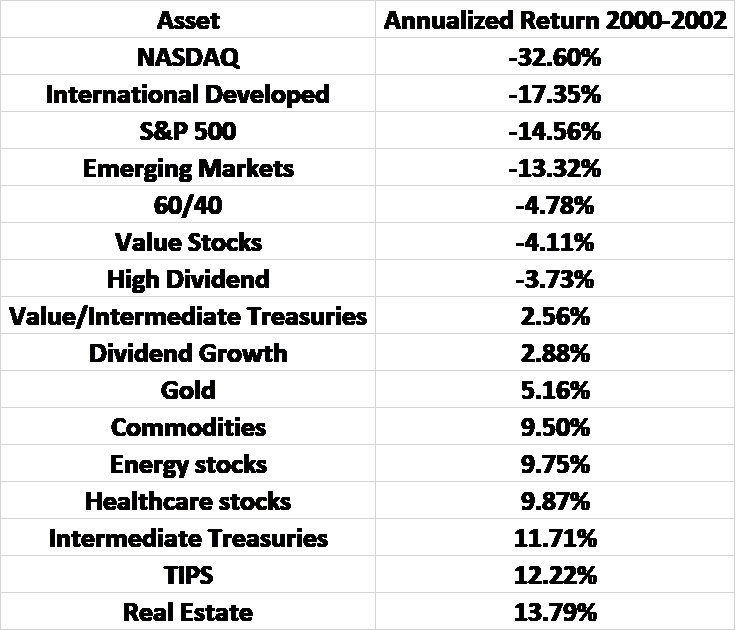

As I said, the comparison to the dot com era is actually very instructive on that score. There were plenty of alternatives back then to holding the obviously overvalued S&P 500 or Nasdaq. From 2000 to 2002 the S&P 500 fell at a rate of 14.5%/year while the Nasdaq fell at more than twice that rate. Even the normally staid 60/40 portfolio lost you money at a nearly 5% a year clip. But there were alternatives, other assets that were very reasonably priced and they performed well during the bear market.

That isn’t always true with bubbles though. The housing bubble that led to the 2008 crisis left nothing untouched in its aftermath. The only assets that put up positive returns in 2007-2008 were cash, bonds and gold. There are very few long term investors who can or should make a tactical change so drastic.

Conditions were similar leading up to the 2022 bear market. The S&P 500 fell 24% to its October low and bonds provided no help, falling nearly 11% for the year. There were some assets that outperformed, mostly value oriented, but they all still lost money. There were only 2 sectors higher for the year (energy and utilities). Commodities did have a good year (+24.1%) but the gains were all concentrated in the first half when Russia invaded Ukraine. The only real alternative to losing money was cash which, at the time, offered negative real returns, which obviously weren’t very attractive.

What about now? Are there assets that are reasonably priced, that we can own now and not worry too much if the AI boom turns to bust? Yes, but there is very little in the US that I would put in that category. One would normally turn to value stocks but large cap value stocks trade for nearly 17 times 2026 earnings. That is cheaper than the index as a whole at 22 times next year’s earnings but not by historical standards. A reasonable P/E for value stocks would be a lot closer to 10 than 20 and single digits aren’t that unusual.

US high quality small cap value stocks (CRSP index) trade for a more reasonable multiple of about 13 times forward earnings and midcap is just a bit more expensive at 14 times. And both have expected earnings growth almost the same as the S&P 500. On a sector and industry basis there’s lots to choose from: Healthcare (especially pharma and biotech), energy (especially natural gas), consumer staples, real estate and materials are all reasonably priced and much cheaper than the market. The S&P 500 isn’t attractive as a whole but parts of it offer real value.

International developed stocks are cheaper than US value at 15 times forward earnings and international value trades at just 11 times next year’s earnings estimate. International small caps are also cheap at 13.5 times and EM is about the same. Latin American stocks are about the cheapest in the world with most markets trading around 10 times 2026 earnings and several in single digits. As a bonus, the region’s voters seem more accepting of market friendly policies for a change. In Asia, Japan trades for about 1 times sales vs 3 times for the S&P 500.

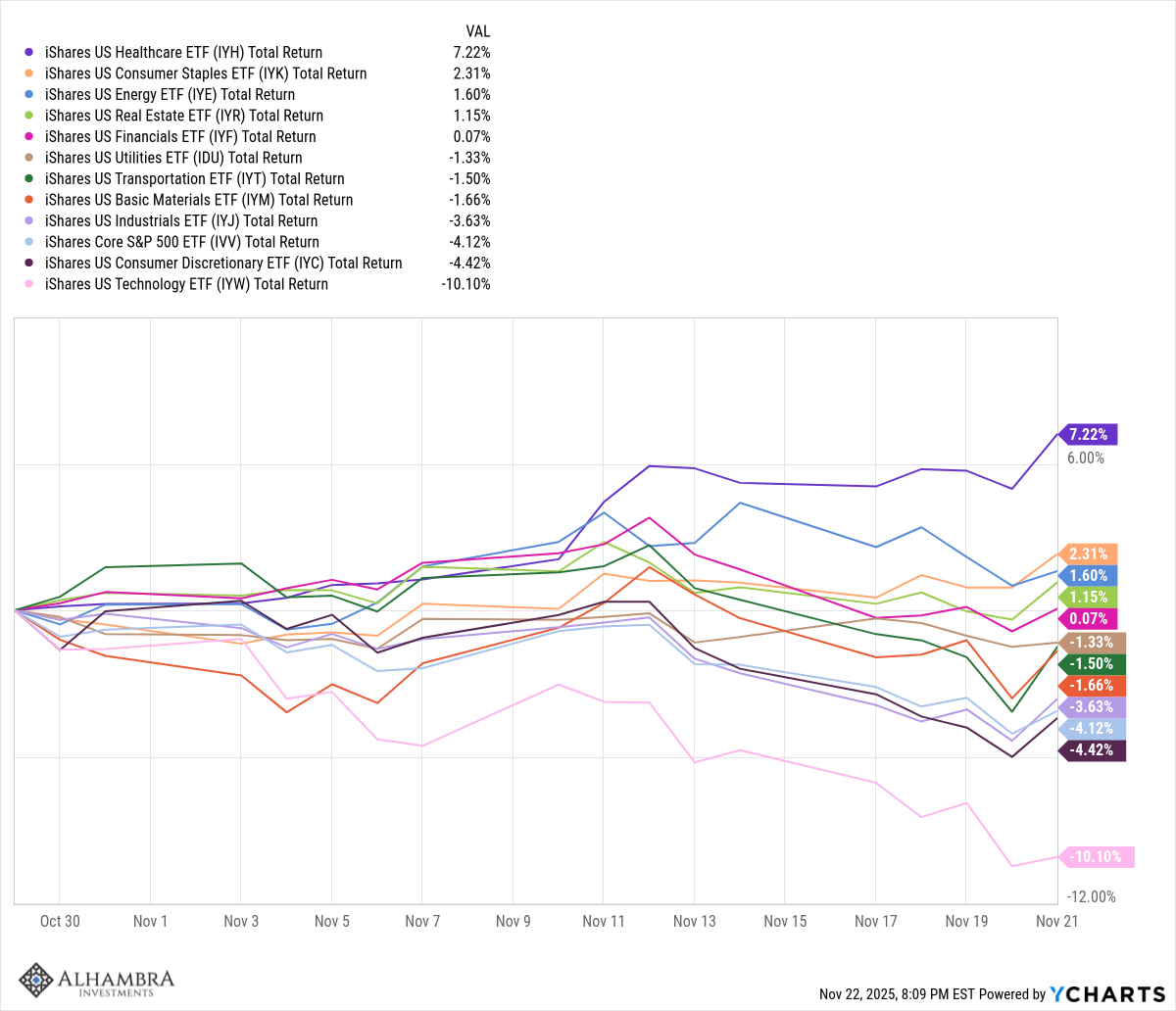

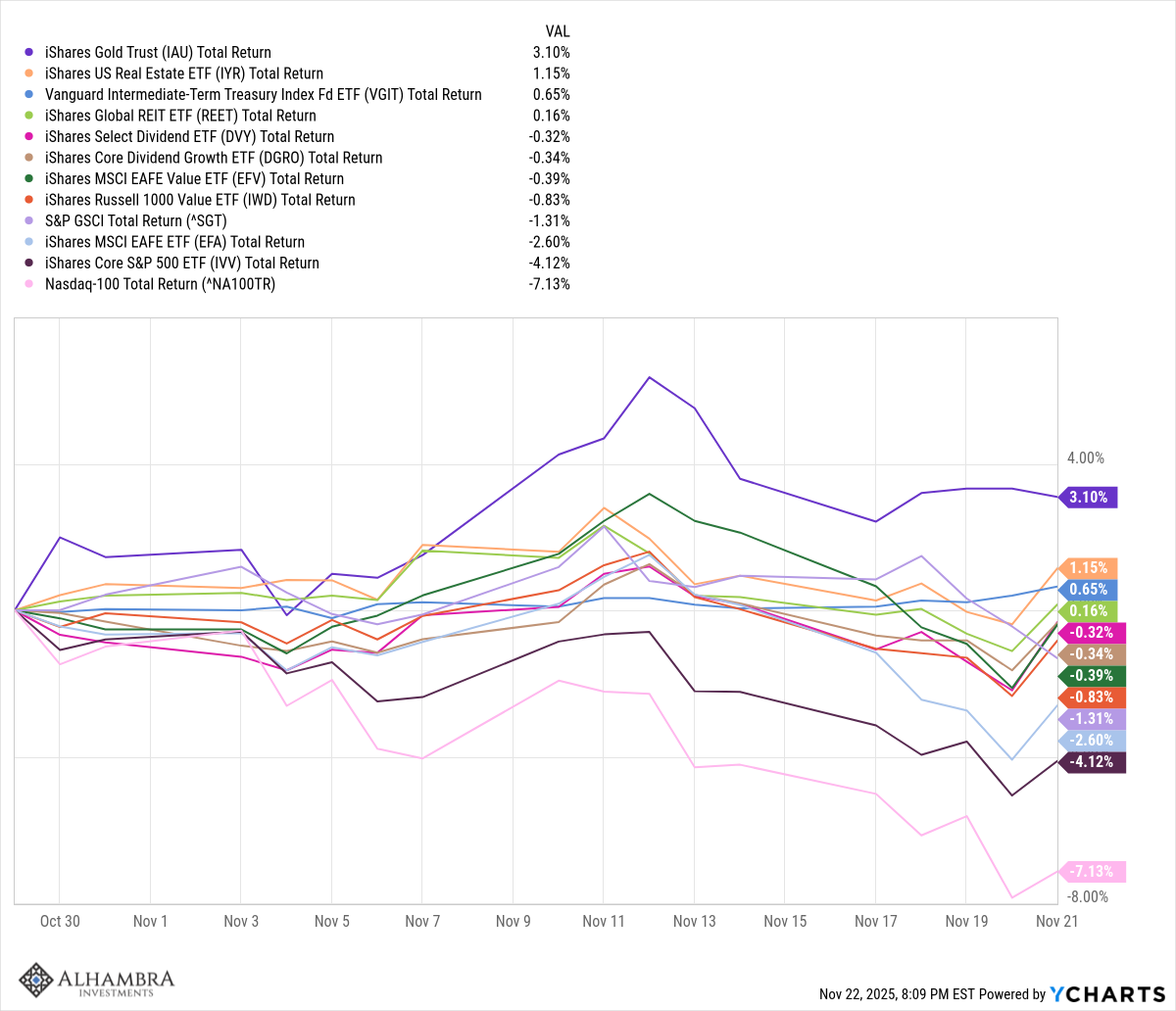

We’ve just had what may be a peek at the future over the last few weeks during this, so far, minor correction. The AI/Tech stock complex peaked on October 29 and since then the S&P is down a little over 4% while the Nasdaq is down 7.1%. Meanwhile, 5 of 11 sectors in the index were higher over that time (healthcare, staples, energy, real estate and financials). Gold, global real estate, intermediate Treasuries, dividend stocks, Latin America stocks, Japan stocks and commodities have all outperformed the S&P and Nasdaq since the peak in late October.

There are plenty of reasonably priced assets from which to choose, so even if you believe this is a bubble and it’s about to burst, that doesn’t mean you have to take drastic measures like you did in 2008 or 2021. Like 2000, there are plenty of alternatives to the popular, expensive stuff. All you have to do is one of the hardest things an investor ever has to do, something even Isaac Newton couldn’t pull off – ignore the hype of a hot market. Newton lost a fortune in the South Sea bubble and famously said:

I could calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of the people

There’s a lot of irrational behavior going on these days too but the last few weeks have seen some sanity return. The Oracle/OpenAI deal announced on September 10th sent Oracle stock up 43% in a day but a little over 2 months later the stock is lower than it was before the deal was announced. The AI hype may already be starting to fade. Since August 1st Meta is down 20.7% and Microsoft 10% while Palantir is flat and Nvidia is up only 3%.

The risk/reward on the potential success of AI is clearly with all the companies that have yet to benefit from it. For the stocks that have benefitted the most from the AI infrastructure buildout, AI has to deliver. If not, these stocks probably have a lot more to fall. If it succeeds, some portion – maybe all – of the potential gain has already been discounted in current prices. But there is no AI premium in most sectors of the market so if it works, they have the most to gain.

Sir Isaac Newton made a profit on his first investment in the South Sea Company. He nearly tripled his money on that first, modest investment and booked a good gain. But when the stock kept rising, he reinvested a larger amount right near the top and lost a substantial fortune. In short, his greed was his downfall. It wasn’t others madness he should have been lamenting but his own. Don’t be a Newton.

More By This Author:

Weekly Market Pulse: This Is Not The Economic Paper You’re Looking For

Monthly Macro Monitor: Investors And Voters Are In A Sour Mood

Monthly Market Review: Is This A Bubble?

Disclosure: This material has been distributed for informational purposes only. It is the opinion of the author and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any ...

more