Does AI Capex Spending Lead To Positive Outcomes?

As someone who views corporate finance through a pragmatic lens, I’ve been closely watching the current surge in capital expenditures (capex) tied to artificial intelligence (AI). The question I’m addressing here is this: when a company spends massive amounts of free cash flow and takes on increasing debt, in this case for AI CapEx, does that lead to a positive outcome for investors? The short answer is that the answer is sometimes yes, but only under particular conditions. If those conditions are not present, the result can be negative. In this post, we will explore the historical context, provide examples, discuss the associated risks, and offer guidance on navigating the current environment.

In a recent post, we discussed how the surge in capital expenditures (CapEx) by the largest U.S. companies has been nothing short of extraordinary.

“Artificial intelligence is consuming capital faster than investors can recalibrate. Bank of America now sees global hyperscale spending rising 67% in 2025 and another 31% in 2026, with total outlays climbing to $611 billion. That is a $145 billion increase in just one month’s estimates.

The surge shows how cloud giants are doubling down. Google raised its 2025 capital budget to $92 billion, Microsoft plans even faster growth into fiscal 2026, and Meta now expects spending of about $100 billion in 2026. Amazon’s data center capacity is on track to double by 2027. None show intent to slow down, even as capex intensity approaches 30% of sales, roughly triple historic norms.

That level of investment is extraordinary. At its peak, the 5G telecom buildout consumed about 70% of operating cash flow, AI infrastructure is now approaching the same strain.

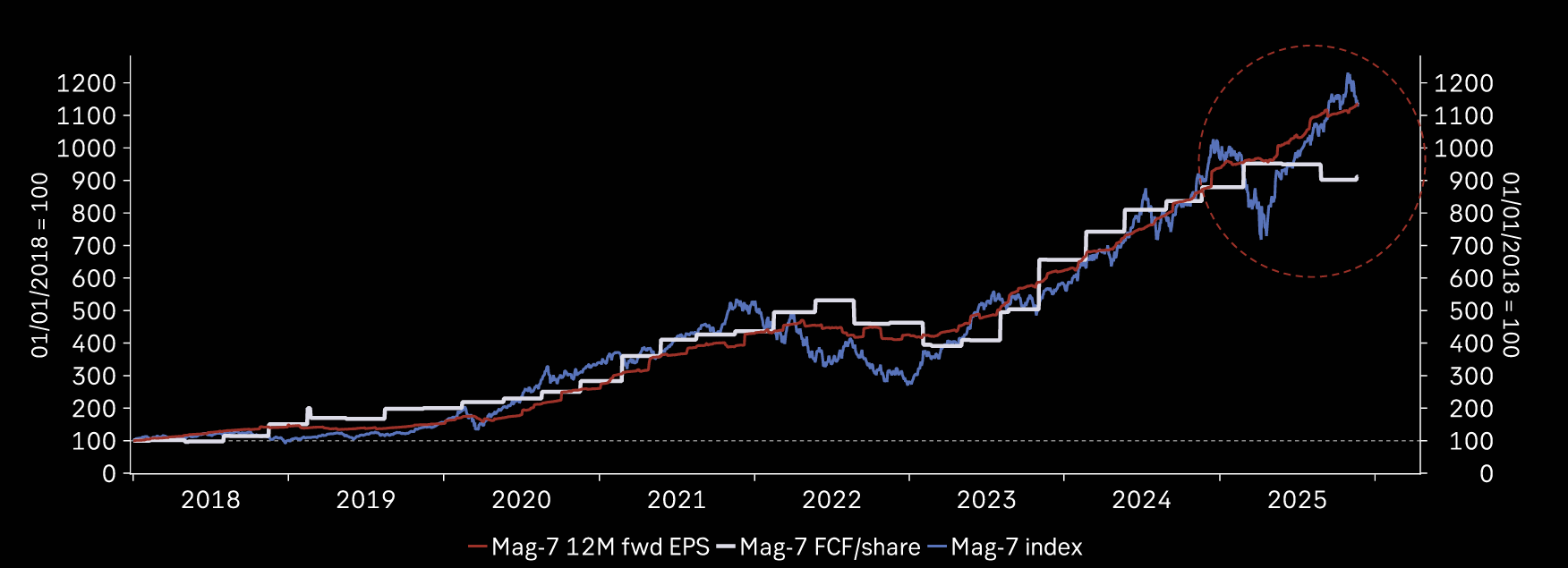

The question, of course, is whether these massive CapEx investments provide adequate financial returns. So far, earnings for the “Magnificent 7” have continued to rise, despite a stagnation in free cash flow due to these massive capital expenditures.

As noted recently by Sparkline Capital, Bain Capital estimates that, to justify their cost, these data centers will need to generate $2 trillion in annual revenue by 2030. Yet, three years after ChatGPT’s launch, AI revenues remain modest, estimated at $20 billion. In other words, revenues need to grow 100-fold to justify the expected buildout. Furthermore, enterprises have struggled to implement AI, and even ChatGPT, the most popular AI consumer application, has yet to fully monetize its users.

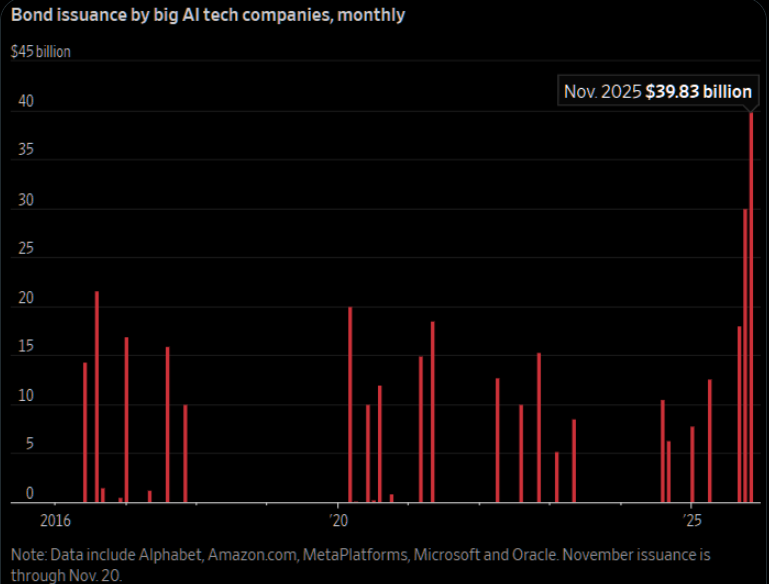

Simultaneously, as free cash flow stagnates, companies are turning to the debt market for the funding they need to meet their AI CapEx requirements.

“The parallels to past technology buildouts are hard to ignore. In the late 1990s, telecoms, such as Global Crossing and AT&T, spent over $500 billion laying fiber optic cable in anticipation of rapid Internet adoption. However, their projections proved overoptimistic, leaving the industry to suffer for years amid a glut of capacity and collapsing prices.” – Sparkline Capital

However, while the current CapEx expenditures seem high, the fundamentals of the companies engaged in artificial intelligence are vastly different than those during the “Dot.com” mania. But even in this case, it does not mean there is no risk in the financial markets.

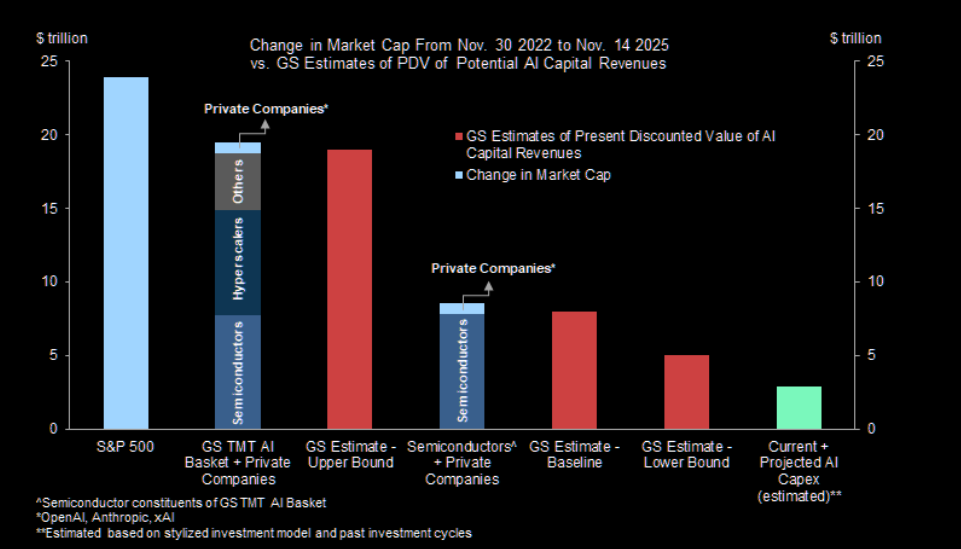

“The good news is that our projections for cumulative AI capex remain well below the incremental capital income that is likely to be created by AI over the next 10-15 years, whose present discounted value we peg at a baseline estimate of $8trn with a range of $5-19trn. The bad news is that the equity market has already built much, if not all, of this value into current prices. These elevated valuations explain in part why our equity strategists expect 10-year returns on US equities to fall short of both the historical US average and the forward-looking non-US average, despite the US market’s greater dynamism and faster earnings growth.” – Goldman Sachs

History can also provide us with some clues as to what is most likely to happen next.

The Historical Capex and Free-Cash-Flow Relationship

Historically, companies have funded investment spending primarily from internally generated funds. In the three decades preceding the 2001 recession, U.S. firms allocated approximately 6 percent of their assets to capital expenditures (capex) and around 89 percent of their cash flow to capex, on average. That close link began to break down after 2000, and by 2015, CapEx had fallen to approximately 4.5 percent of assets, and has now fallen to 3.5%. It is worth noting that historically, the capital expenditure (CapEx) spending by the top-7 companies has mostly correlated with the rest of the economy. However, this correlation changed with the onset of the COVID pandemic, when companies shifted to increase profitability and productivity through technology to offset the economic shutdown’s impact.

From academic research, the relationship between free cash flow and capital investment is not uniformly positive. One study found that capital spending is directly associated with the size of free cash flow. Another found that leverage, or debt, has a negative association with future CapEx. Specifically, a 1-point increase in the debt-to-assets ratio reduced capital expenditures relative to assets by approximately 0.07 points. What this tells us is that a company with healthy free cash flow is better positioned to invest. But increasing debt may act as a drag on investment if not paired with a strong opportunity. Capex only adds value when it leads to incremental returns above the cost of capital.

That is currently the hope of the market; however, prior cycles of heavy investment may tell a different story. As Sparkline noted:

“Over a century before the Internet, railroads revolutionized the American economy. Following the Civil War, the boom began in earnest, with over 33,000 miles of tracks laid from 1868 to 1873. The next exhibit compares the scale of the current AI boom to the railway and Internet buildouts.”

Then, during the late 1990s, the telecom and IT sector expanded rapidly. Firms built infrastructure, laid fiber, and rolled out broadband. But many of those investments didn’t generate the expected returns. Some companies incurred heavy debt, and when demand growth failed to meet expectations, they faced write-downs and restructuring.

“Relative to GDP, current AI spending already exceeds the peak achieved in the Internet boom. While it remains below the peak attained in the railroad buildout, the useful life of AI chips is much shorter than that of railroads. If we adjust for faster depreciation, today’s AI buildout tops the chart. While the railroads and Internet proved transformative, how did shareholders in the firms building these technologies fare? The next exhibit shows the stock prices of railroad and telecom stocks during their respective booms.” – Sparkline

These two examples illustrate the risk that spending without commensurate returns destroys shareholder value. If demand is ultimately unable to keep up with the influx of new supply coming online, it will cause prices to crater and saddle firms with years of excess capacity. Corporate values collapse, with those that took on debt to finance the buildout facing the risk of bankruptcy.

The current AI CapEx wave is arguably larger than both of those previous examples. If the revenues materialize as expected and demand exceeds supply, those who invested in the space early will be the primary beneficiaries. However, that is the basis of all investing: measuring risk versus opportunity.

Risk Or Opportunity?

What are the risks and opportunities of spending large amounts of free cash flow and increasing debt levels?

- There is the risk of capital allocation without return. AI CapEx is only worthwhile if it produces a return above the cost of capital. Academic work affirms that capital expenditures have a positive effect on firm value only if they are profitable. If the investment yields sub-par returns, value is destroyed.

- Increasing leverage reduces future investment flexibility. Research reveals a strong negative correlation between leverage and future capital expenditures. Firms with greater debt invest less. In the AI context, if a company borrows heavily to finance capex, it may have less capacity to adjust or redeploy capital when conditions change.

- There’s the risk of free cash flow saturation. When firms commit large proportions of FCF to capex, they reduce or eliminate funds available for dividends, buybacks or other shareholder returns. One market comment warned investors to be wary of companies whose capital spending is growing faster than revenue, especially if they’re issuing debt to finance expansion.

- Timing the investment cycle poorly can have consequences. If capex coincides with the top of a cycle, firms risk entering periods of lower demand and lower asset utilization. The correlation between capital expenditures (capex) and cash flows dropped significantly after 2000, indicating that many firms are spending without a clear anchor to actual earnings or liquidity.

- Execution and monetization risk. Spending on AI infrastructure doesn’t guarantee revenue or profit. One study introduced the Capability Realization Rate model, which highlights valuation misalignment when expectations exceed realized performance. There is a risk that investments may not be monetized or that competitive advantages may disappear.

Despite those risks, there are conditions under which opportunity thrives. The questions that investors must answer correctly are:

- Does the firm have a clear investment opportunity? If AI infrastructure enables a hyperscaler to expand its addressable market or materially improve margins, then the return on capital can exceed the cost.

- Is free cash flow coverage sufficient? If the firm uses free cash flow rather than only debt to fund the capex, financial strain is lower.

- Are debt levels moderate and manageable? If growth is strong and debt is controlled, using leverage to accelerate growth is rational.

- Does the company have execution capability and a clear monetization path? Without this, the spending becomes a liability.

- Does CapEx align with shareholder return expectations? If the company balances future growth with returning capital to shareholders, then value is more likely to accrue.

For most of the Magnificent-7 companies, most of those answers are “yes.” However, the question of a “clear monetization path” remains unclear.

I believe that we are still in the early stages of the current cycle, but many risks could negatively impact returns in the future. As such, we should consider a set of actionable guidelines as we participate in the current market.

- Focus on firms with disciplined capex and clear ROI. Prioritize companies that articulate a credible path from capital expenditures to incremental cash flow and have historically generated high returns on invested capital. Avoid firms that are simply raising debt, spending aggressively, but lacking clear revenue targets or margin expansion.

- Check the debt liberalization. Assess the debt levels, interest coverage, and maturity profiles. If a firm is issuing large amounts of debt while FCF is stagnant or declining, that is a warning sign. For example, commentary noted that major tech firms “are using debt” to fund both capex and buybacks concurrently.

- Monitor free cash flow coverage of capex. Determine what proportion of FCF is being used for capex (and debt servicing). If FCF is fully absorbed into capital expenditures, leaving nothing for dividends, buybacks, or debt reduction, risk is elevated.

- Screen for early‑stage misalignment. Use the CRR framework: are valuations based on near‑term returns, or purely on slender hopes? Academic research shows markets reward the “potential” but punish when returns don’t materialise.

- Consider the macro backdrop. In a tightening interest rate environment, debt financing becomes more expensive; asset utilization may also be challenged if demand growth slows. Some research suggests that the correlation between capital expenditures (capex) and cash flow declines during weak economic cycles.

- Balance growth and value orientation in your portfolio. If you are investing in high-capex companies, ensure that a portion of your portfolio also includes more conservative firms that return cash to shareholders, thereby reducing overall portfolio risk.

The current AI CapEx wave represents one of the most significant investment cycles in recent decades. However, significance does not guarantee success, and heavy spending of free cash flow and elevated debt levels must lead to value creation. Those massive investments must yield returns, debt must remain manageable, and cash flows must support those expenditures. Without such results, it can erode value and expose you to downside risk.

You, as the investor, must assume the role of financial disciplinarian. The direction is promising, but the execution will be critical. There are clearly risks present, and, as such, it is crucial to remain disciplined, measure carefully, and allocate risk accordingly.

More By This Author:

A Third Of US Debt Matures In 2026

Hawkish Or Less Dovish? QE Or Not QE?

Hassett To Replace Powell: Betting Markets Are Confident

Disclaimer: Click here to read the full disclaimer.