What Is Holding Down Long-Term Interest Rates?

It was just a month ago that bond investors were told to brace themselves for a run-up in the yield of 10-year US Treasuries, perhaps to 4 per cent. Citing strong U.S. growth, falling unemployment rates and the prospects for higher wages contributing to a pick up in inflation, forecasters warned bond investors that the three - decades old decline in bond yields was over. The Fed signaled that it would not be swayed from its anticipated further rate hikes this year. Long-term rates were expected to increase and the yield curve would adopt a more positive slope, away from its flattening of recent months.

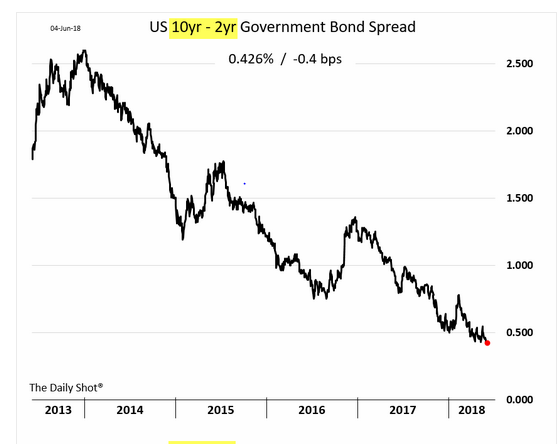

We have seen this movie before. This is not the first time since the 2008 financial crisis that the U.S. bond market has contradicted bearish sentiment. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note today is 2.95 %. Meanwhile, the yield on the comparable Treasury Inflation-Protected Security, or real yield, is trading at 0.80 % compared to 0.95% in mid-May. Inflation-adjusted yields on government bonds in major markets around the globe have retreated from their May highs, a sign that investors don’t believe the world is poised for a sudden acceleration in economic growth. While most of the yield curve flattening can be attributed to the run-up in short-term rates in response to Fed policy, the long -end of the yield curve has dropped of its own accord. The 10yr-2yr spread has collapsed from over 250 bps in 2013 down to just under 50 bps today.

Flattening of the US Yield Curve

In its most recent newsletter, Bianco Research[1], says

“…Blame slowing global growth for still low U.S. Treasury term premium and real yields. The U.S. may be growing at a moderately strong rate, but economists and bond investors are still very hesitant to join the chorus of optimism found within nearly all survey output. Longer-end yields should struggle to rise until these concerns erode.”

The “term premium” is that excess yield that investors require to hold a long-term bond instead of a series of shorter-term bonds. The term premium measures the degree of uncertainty in the bond market. Today, with the 10-yr bond yielding 2.95 %and the 2-yr yielding 2.50 %, the term premium is 40 bps. Put differently, long-term investors do not require a higher rate of return in order to place their funds 10 years out. Their comfort level regarding the future path of short-term interest rates is satisfied with just 40 bps over the 2- yr bond.

Overshadowing U.S. growth is the economic outlook outside the United States. Financial markets are incorporating a series of related changes in growth and inflation worldwide. Japan and Germany now anticipate slower growth than was forecasted earlier in the year. The outlook for the U.K. continues to be buffeted by uncertainty over Brexit. The Eurozone debt crisis has re-emerged, featuring a highly volatile Italian bond market. Key emerging market economies, such as Turkey and Argentina, are suffering from large current deficits and a huge exposure to USD dominated bonds. Finally, the rather erratic U.S. trade policy adds greatly to the atmosphere of uncertainty worldwide.

[1]U.S. Real Yields Stuck at Range Highs, Blame Slowing Global Growth, June 4, 2018

I think you are right. Pension funds need that locked yield and swoop down to buy when yields go up,even a few bps.

Maybe long bonds are simply too valuable as collateral and are being hoarded, Prof.