The Nguyens And The Fed

Monetary policy was once quite simple. Unfortunately, the Fed made things more complicated in 2008 when they began paying interest on bank reserves. You cannot have any hope of understanding our complex modern policy regime unless you first understand the fairly simple system of the early 2000s. And hardly anyone does understand that system. If you read this post, you’ll be among the tiny group that do.

My dissertation at the University of Chicago studied currency hoarding. At the time, more than 2/3rds of the currency stock seems to have been hoarded, that is, used as a store of wealth rather than a medium of exchange. Today, the proportion is likely even higher, although we lack precise data. One suggestive fact is that over 80% of currency (by value) is $100 bills. And while smaller denominations wear out quickly and must be frequently replaced, $100 bills last for a very long time, suggesting that they are not widely circulating.

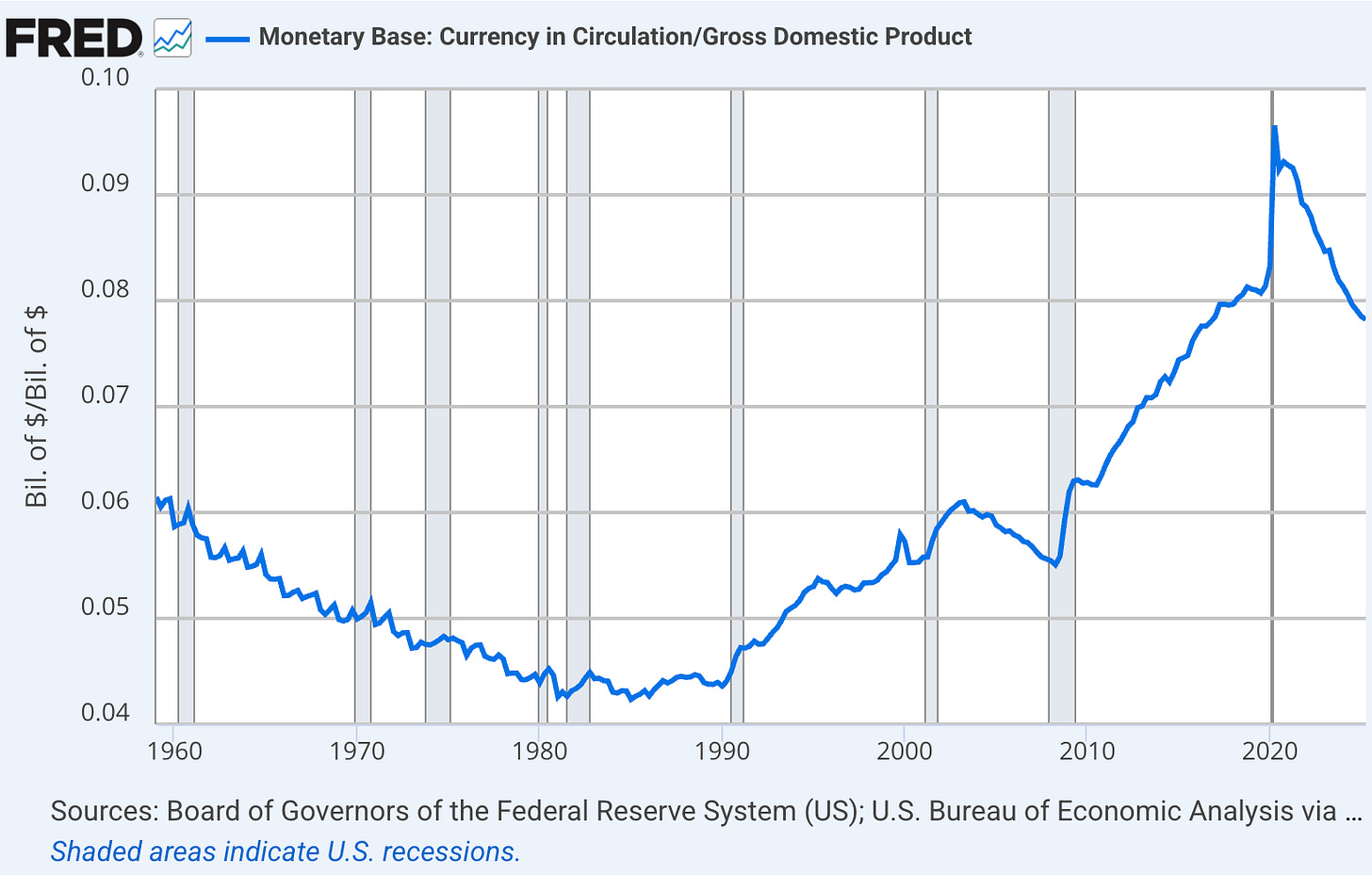

In my study, I found evidence that the demand for hoarded currency is heavily influenced by two factors—nominal interest rates (i) and marginal income tax rates (MTR). You can think of the nominal interest rate as the opportunity cost of holding zero interest currency. You can think of the marginal tax rate as the benefit of hiding income from the IRS. I found that the ratio of marginal income tax rates to nominal interest rates (MTR/i) is strongly correlated with the ratio of currency holdings to GDP.

Interest rates are far more volatile than marginal income tax rates. In recent decades, changes in the MTR/i ratio have been mostly driven by changes in the denominator. As interest rates soared between 1960 and the early 1980s, the demand for hoarded currency declined to just over 4% of GDP. Interest rates fell sharply by the early 2000s, and the currency stock rose to about 6% of GDP. The long period of near zero interest rates during the 2010s pushed currency demand up to about 8% of GDP, with a brief spike up to nearly 10% during Covid. I suspect that foreign demand for US currency was also increasing during this period. Now the ratio is once again falling, a response to higher interest rates in recent years.

(Click on image to enlarge)

When people think about currency hoarding, they often visualize foreign demand for dollars and drug smuggling. Those are significant factors, but a large share of currency demand is otherwise legal American businesses and individuals hiding wealth from the IRS. Here’s a recent article from the Orange County Register:

Irvine couple with jewelry businesses hid $127 million in cash from the IRS, feds say

An Irvine couple accused of failing to file IRS forms for more than $127 million in cash from their precious metal businesses in the downtown Los Angeles’ Jewelry District have pleaded guilty to criminal charges, federal prosecutors announced on Friday, Dec. 19.

Alex Nguyen, 50, and Sam Nguyen, 52, owned various businesses that bought and sold precious metals, including Newport Gold Post, Sam Bullion and Coin, AAPS Bullion and Goldtech Assay Laboratory LLC, which did business as Infinity, according to their plea agreement.

As they were bringing in millions of dollars in cash – sometimes $200,000 to $1 million daily – the couple was required to file forms with the IRS to report all cash transactions over $10,000, but they repeatedly “knowingly and intentionally” did not file these forms, the U.S. Attorney’s Office stated.

Prosecutors said the pair hid cash, used unreported cash at separate family businesses and casinos, failed to maintain an anti-money laundering program, and accepted large amounts of cash without asking buyers for identification.

Think of it this way. If tax rates are 30% and nominal interest rates are 6%, then it would be profitable to store income in the form of currency for up to roughly 5 years before you would have been better off paying the tax and earning 6%/year interest. That’s why the ratio of tax rates to interest rates (MTR/i) is so important for currency demand. This ratio is the key determinant of the ratio of currency to NGDP, with the proviso that hoards of cash adjust to changes in MTR/i with a time lag.

For any given ratio of currency to GDP, a change in the currency stock will change NGDP in the same proportion. Prior to 2008, the monetary base was about 98% currency. That meant that as a rough approximation, any exogenous change in the monetary base led to a roughly equal percentage change in the currency stock. If people wish to hold 6% of national income in cash, then increasing the stock of cash by X% will tend to increase NGDP by X%.

Prior to 2008, the Fed determined the path of NGDP by adjusting the amount of currency in circulation. To be clear, the ratio of currency to NGDP (which is the inverse of the velocity of circulation) was not a constant. But the ratio was stable enough so that the Fed could offset any change in the public’s desired currency/GDP ratio with a suitable change in the currency stock. That’s why it is exogenous changes in the currency stock that matter. If the Fed wanted NGDP to grow over time, they’d add more currency to the economy than the public (including money hoarders) currently wished to hold (as a share of national income.) The public would try to get rid of these excess cash balances by spending them.

Here’s where the fallacy of composition comes into play. At an individual level, people can get rid of excess cash balances by spending them or putting them in the bank. But in aggregate they cannot, at least in nominal terms. The only way that society as a whole can get rid of excess cash balances, the only way they can achieve their desired currency/GDP level, is by boosting spending until there’s enough inflation to justify their newly enlarged currency holdings.

I know this is going to sound weird to most people but prior to 2008, monetary policy had little or nothing to do with the financial system. It was mostly a game played between the Fed and (alleged) money hoarders like the Nguyens. Just as OPEC can impact the price of oil by adjusting the rate at which oil is being injected into the global economy, the Fed could impact the purchasing power of money by adjusting the rate at which currency was being supplied to the public—mostly supplied to money hoarders evading taxes.

Banks did not play an important role in this process. Currency was injected into the economy in two stages. Base money was directly injected via open market purchases of Treasury bonds. But the effect would have been almost exactly the same if the base money had been injected by paying the salaries of federal employees with newly created cash. Almost immediately after the new base money was created, it was converted from bank deposits at the Fed to currency in circulation. The fact that the new base money briefly consisted of bank deposits as the Fed has fooled people into thinking that banks played an important role in the monetary policy process. This is false. The effect would have been almost identical under any reasonable system of injecting new currency, even one that entirely ignored banks. Indeed, it would have had roughly the same effect even in a world where banks did not exist.

Monetary policy does impact the financial system, but only because NGDP shocks impact the financial system.

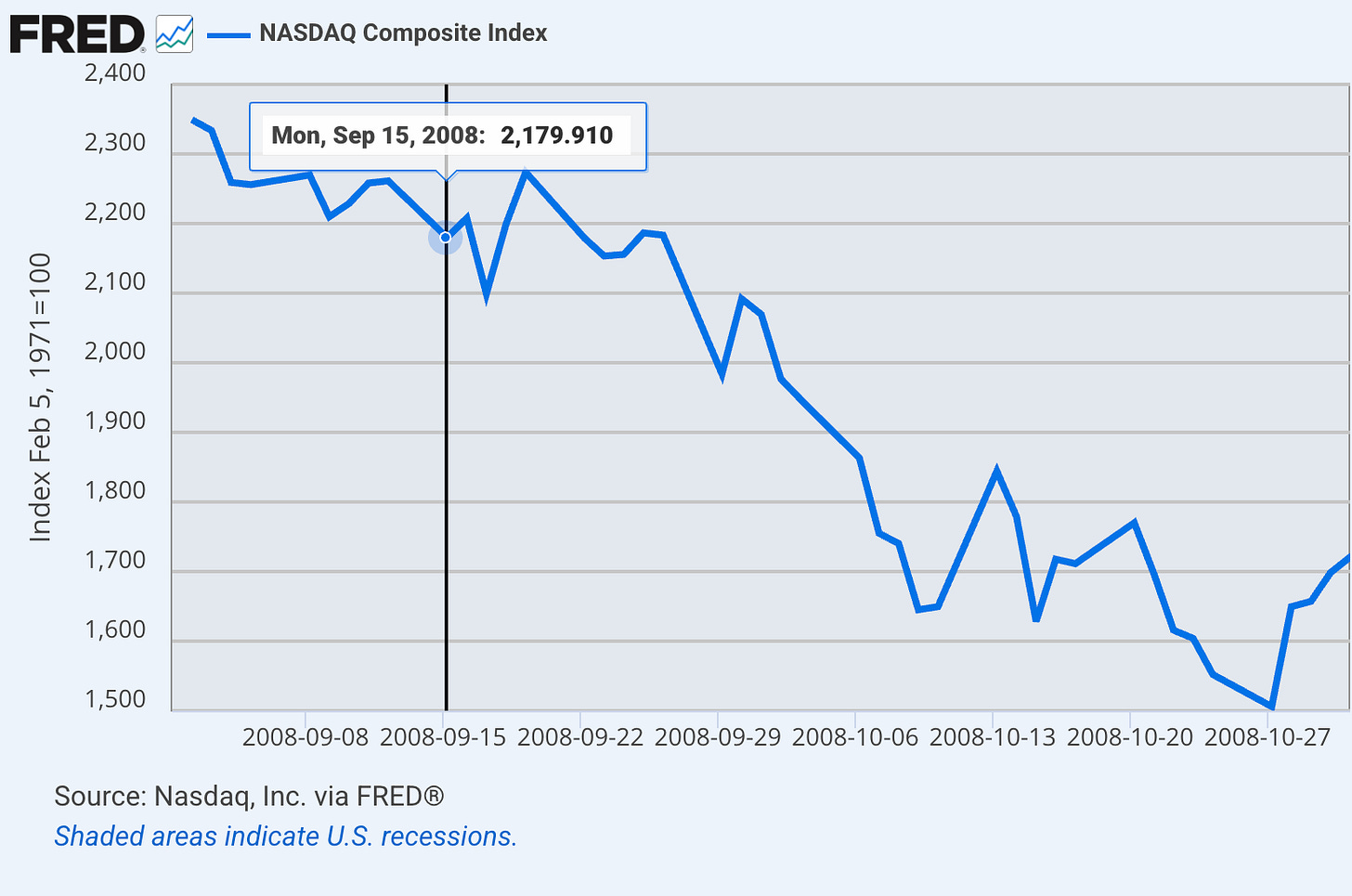

In late 2007 and early 2008, the Fed dramatically slowed the growth rate of the currency stock. This tipped the economy into recession in late 2007. In early October 2008, they started paying interest on bank reserves. Now banks did begin to play a significant role in monetary policy. Interest on reserves caused more demand for base money, which triggered expectations of falling NGDP. This sharply depressed stock prices as investors began to anticipate a deep recession. (Stocks fell far more sharply in early October than they did after Lehman failed on September 15th). The Fed ruined a nice, simple, effective system for controlling NGDP growth.

(Click on image to enlarge)

But that’s a story for another post. You cannot possibly understand what went wrong in 2008 without first understanding the much simpler policy regime of 2007, when it was all about Fed control of the currency stock.

Some people might object to this explanation by pointing to the fact that, prior to 2008, the Fed targeted interest rates and the currency stock was seen as being demand determined. This is highly misleading. Yes, the Fed set a target interest rate, but it was set at a level expected to produce the sort of change in the currency stock that was likely to achieve their policy goals. Interest rate control was a means to an end—the control of the currency stock. It was the path of currency relative to the demand for currency that determined macro aggregates like the price level and NGDP. Printing money was the actual policy; interest rates were just a tool to control how much money was printed.

PS. You might notice that money demand is heavily influenced by the ratio MTR/i. That means that higher interest rates reduce money demand. But lower money demand is actually expansionary. That’s right, other things equal, higher interest rates tend to raise NGDP. Of course, “other things equal” is doing a lot of work in this claim. For instance, a higher rate of interest paid on bank reserves is contractionary. The debates between the Keynesians (who view higher rates as contractionary) and the NeoFisherians (who view higher rates as inflationary) is frustrating to watch, as the participants don’t seem to pay enough attention to the question of what causes the interest rate to change. As always, never reason from an interest rate change. Interest rates are not monetary policy, they are an epiphenomenon of policies that change the supply and demand for base money.

Photo by Colin Watts on Unsplash

PPS. Ten years ago, I warned that America was becoming a banana republic. Today, this claim is one of those “the sky is blue” observations, so I won’t waste time railing against every new Trump outrage. FWIW, back in May I suggested that Powell might stay on as the (de facto) leader of the Fed, even after 2026. Today, that outcome seems ever more likely. Trump may be overplaying his hand.

More By This Author:

13 Years Later: The Lessons Of Abenomics

Core Nominal GDP

The Great Depression: Elevator pitch