13 Years Later: The Lessons Of Abenomics

Image Source: Pixabay

Here’s the TLDR:

Monetary policy can control nominal aggregates, even at the zero lower bound.

Monetary policy can address real problems caused by unstable nominal aggregates.

Monetary policy cannot address real structural problems.

Japan is a near perfect example of all three claims. I hope this post will also dispel a few myths about Japanese inflation, interest rates, exchange rates, fiscal policy, etc.

In late 2012, presidential candidate Shinzo Abe promised Japanese voters that he would create higher inflation. He went on to achieve a series of impressive electoral victories. So much for the claim that voters hate inflation. (They hate some types of inflation—not all.)

[As an aside, at roughly the same time the Fed committed to a more expansionary monetary policy, which ended up fully offsetting the effects of fiscal austerity, contrary to predictions of Keynesian economists that expected the fiscal austerity to discredit market monetarism. Instead, their failed predictions of a slowdown in the economy during 2013 discredited simple Keynesian models that ignore monetary offset.]

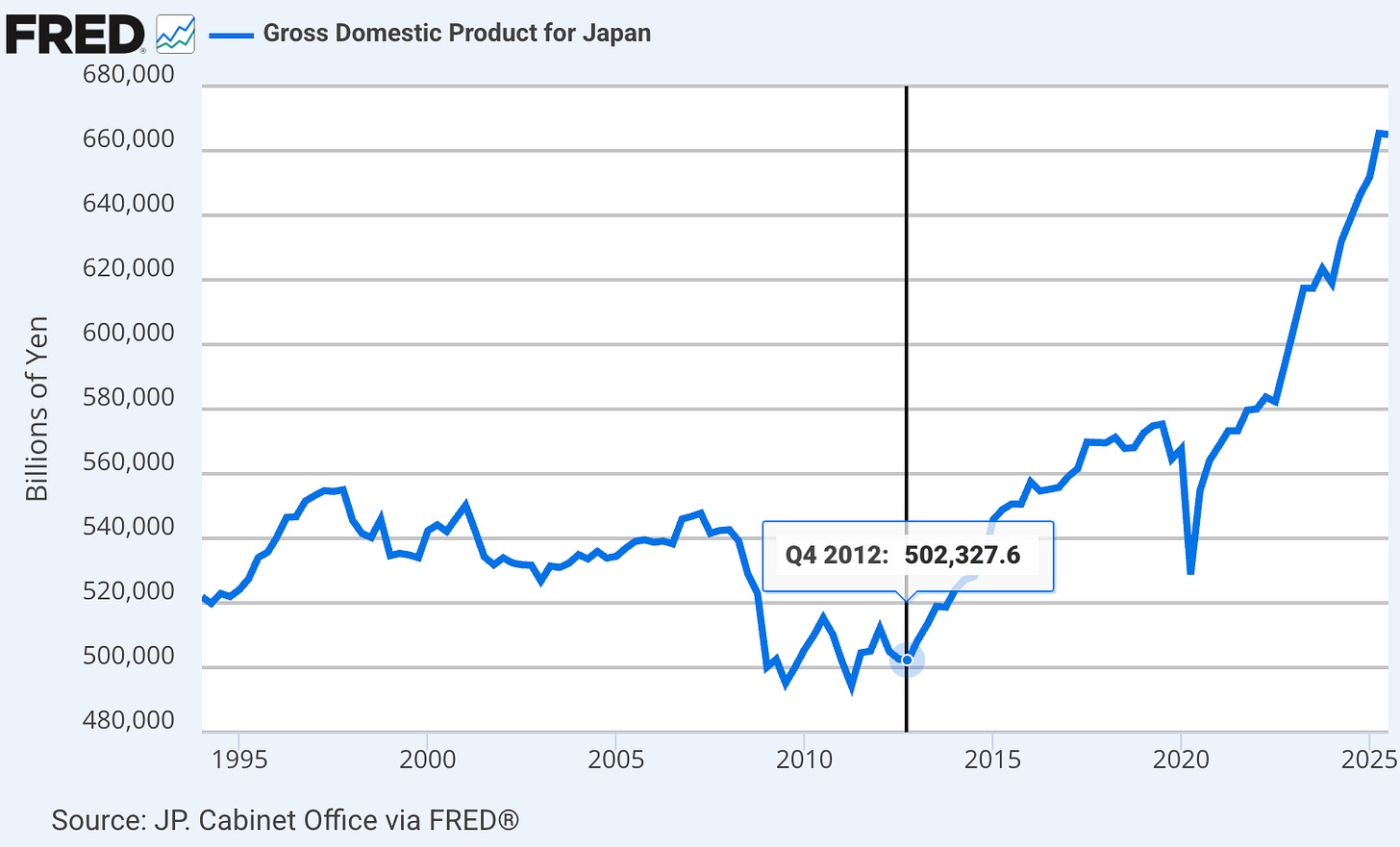

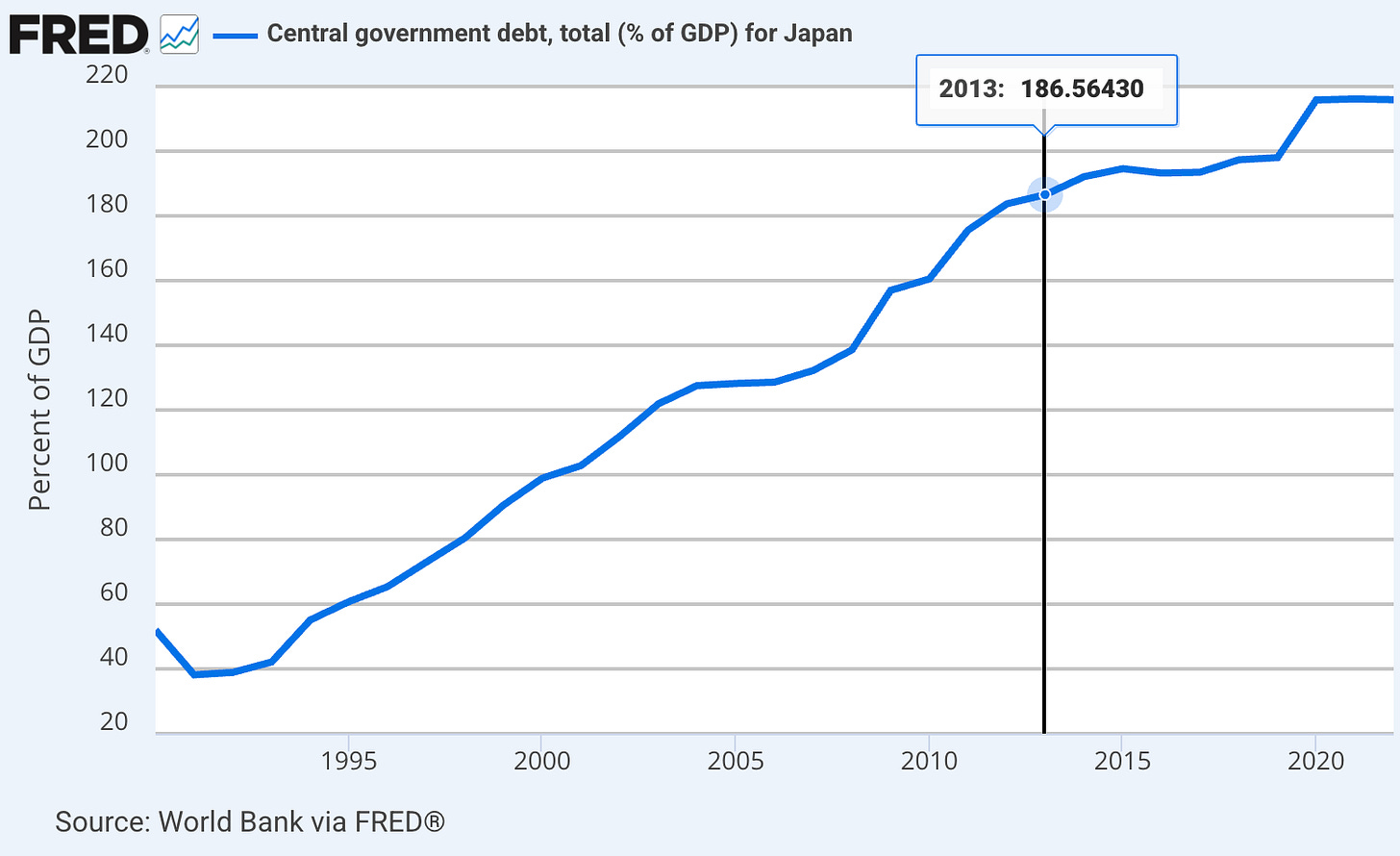

By the time Abe took office at the beginning of 2013, Japan had experienced nearly two decades of very mild deflation, and near zero NGDP growth. This deflation had occurred despite one of the most reckless fiscal expansions in human history, pushing Japanese public debt much higher as a share of GDP.

Interest rates were stuck at zero, and many economists argued the BOJ was “out of ammunition”. Instead, Abe’s policies ended deflation and led to significant growth in nominal GDP, which has continued right up to the present:

(Click on image to enlarge)

This growth in NGDP occurred despite the fact that Abe instituted a tighter fiscal policy, which greatly reduced Japanese budget deficits. Other than a single year during Covid, Japanese public debt has leveled off as a share of GDP. So much for “fiscal dominance”:

(Click on image to enlarge)

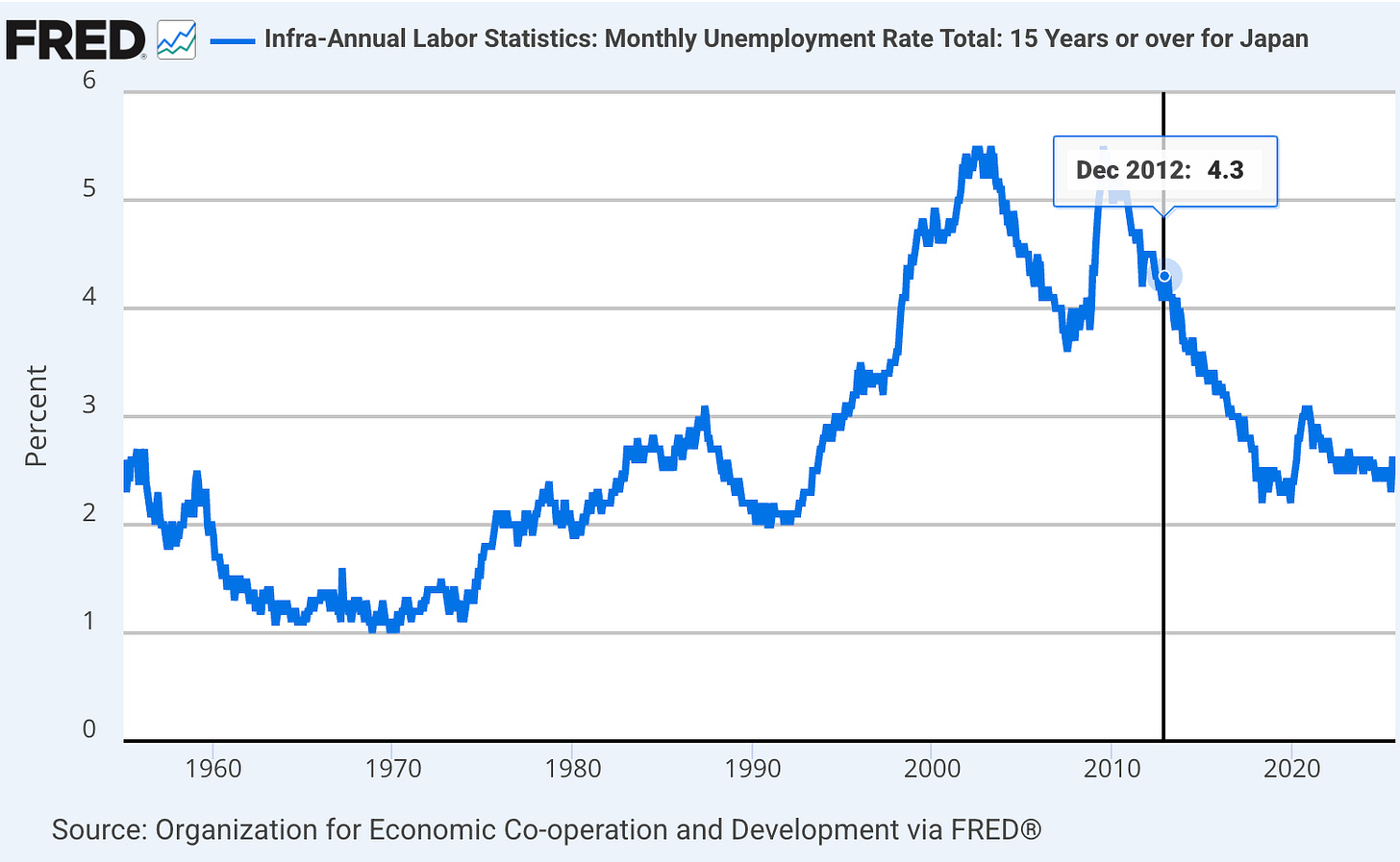

As predicted by the musical chairs model, the growth in NGDP helped to return Japanese unemployment back to its historical norms of close to 2%. Most real problems are structural and cannot be solved by improved monetary policy. One problem that can be solved is high unemployment that is caused by insufficient nominal growth:

(Click on image to enlarge)

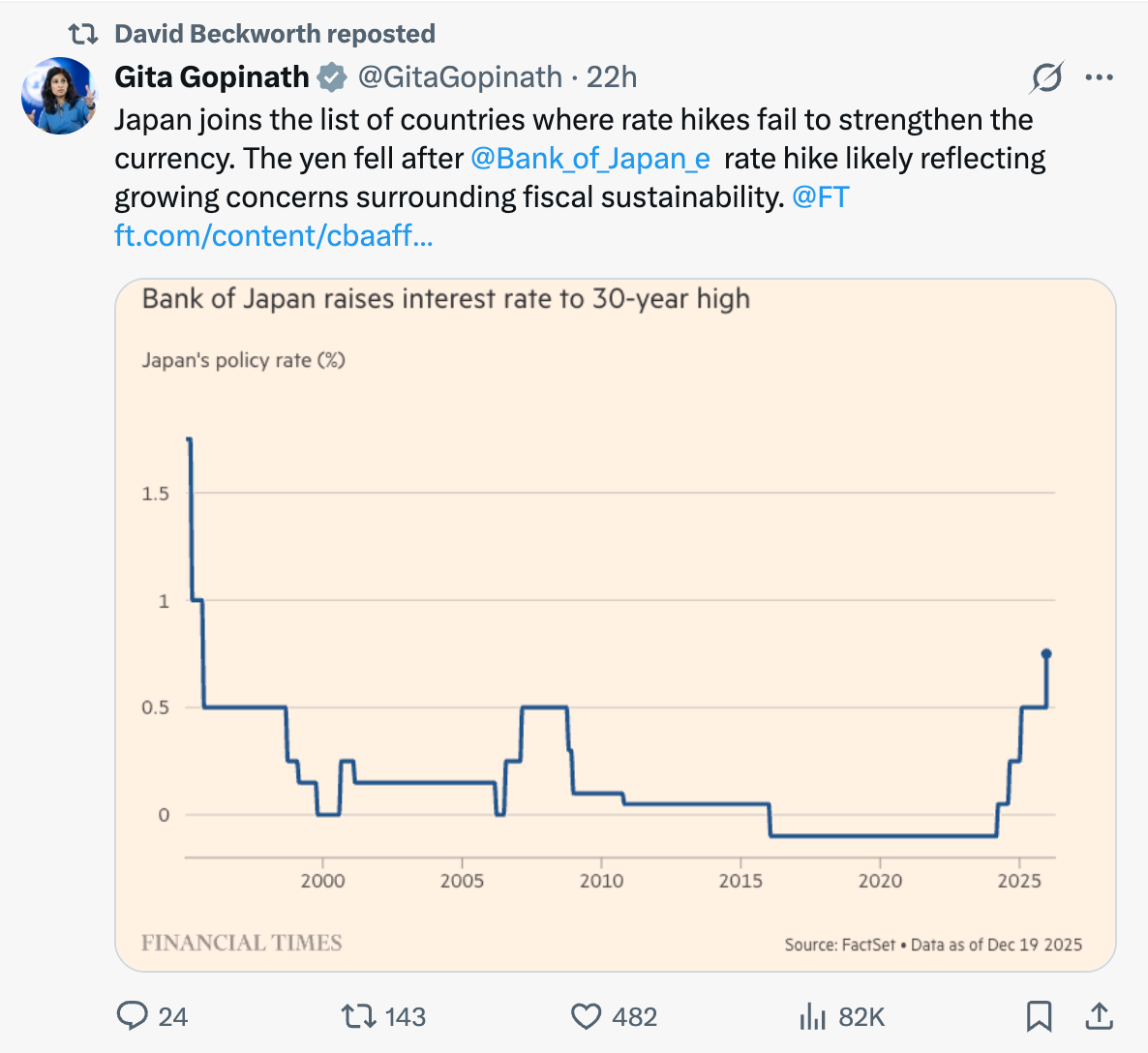

Many people are surprised by the fact that Japanese interest rates have recently been increasing, after a period of nearly 30 years of near-zero rates. I am surprised that Japanese interest rates remain so low, far below levels in countries such as the US, despite solid NGDP growth.

Yes, it’s a “30-year high”. But the short-term interest rate is still only 0.75%.

Other pundits also worry about fiscal dominance:

“Things to come”? Maybe, but exchange rates are close to a random walk.

Back in the 2000s, I warned that Japan was making a mistake running large budget deficits and that what they really needed was monetary stimulus. In the 2010s, I made the same criticism of US budget deficits. Each time, I was told “deficit don’t matter” because interest rates were low at the time. I pointed out that rates might not stay low forever, and that these debts would still be on the books when interest rates started rising.

Now I’m being told that the public debt situation is so bad in Japan and the US that the situation is almost hopeless, and that we will have to monetize the debt with an easy money policy and give up on 2% inflation. That’s what people mean by “fiscal dominance”.

I’m not buying either argument. It was never true that “deficits don’t matter”, and I don’t believe that the US and Japan are now stuck with fiscal dominance. If we end up with high inflation it will be because the Fed screwed up with a flawed Phillips Curve model (as they did in the late 1960s, and again in 2021-22), not because they were forced to inflate. Not only is the public not clamoring for the Fed to inflate the price level, voters have now decided that inflation is public enemy number one. I believe the public overrates the harm done by inflation, but in this case I’m sort of pleased with the misconception—it will help us to avoid fiscal dominance.

Yes, it is possible that at some point in the distant future the US might experience fiscal dominance. That would occur if our government continues down the road to banana republicanism. But it is also possible that at some point we come to our senses and address the budget deficit, as we did in 2013 (before reversing all those gains five years later.) As long as the Fed targets inflation at 2%, Congress will be forced to eventually address the budget. That’s what it means to have monetary dominance.

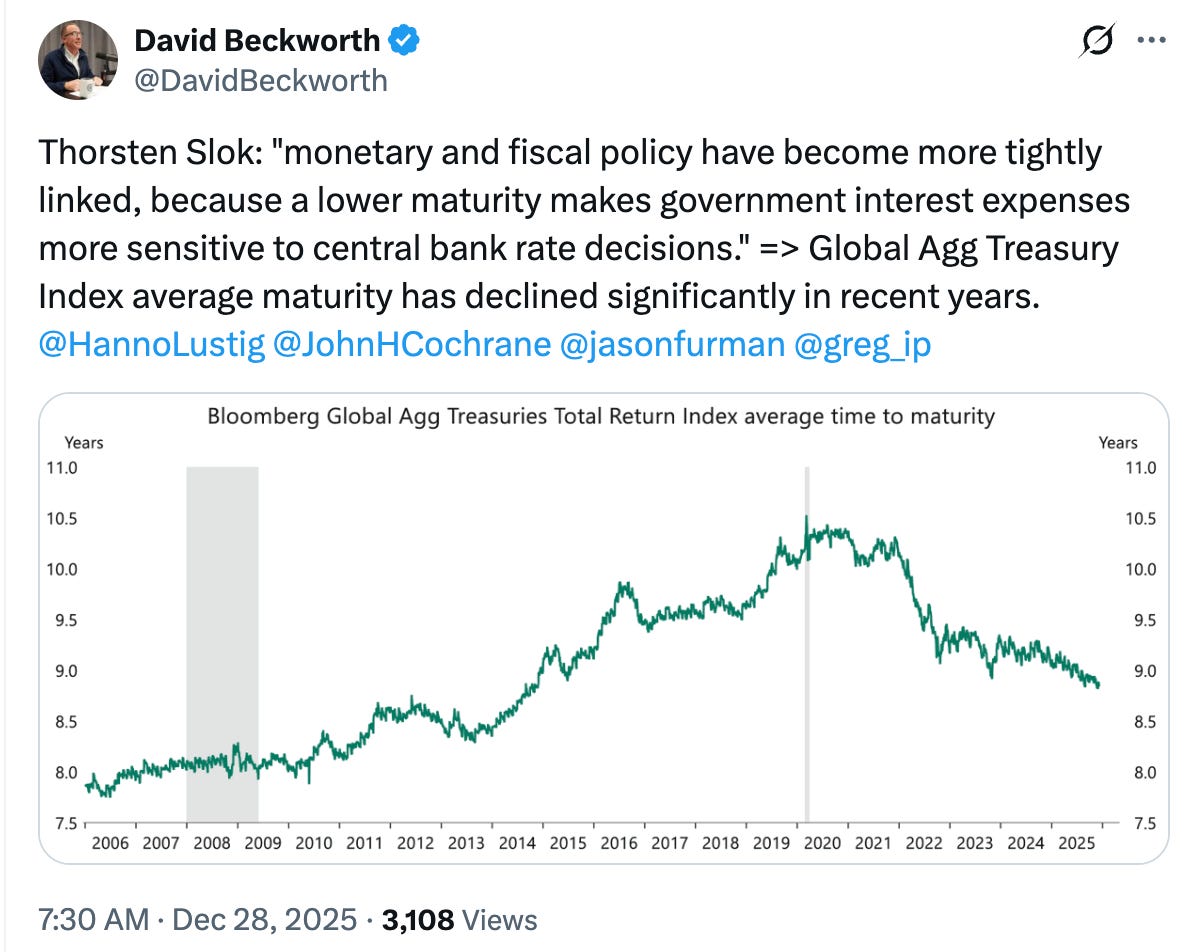

If Congress wishes to impose fiscal dominance, they would eventually need to tell the Fed to raise its inflation target above 2%. And don’t assume that 3% would solve the problem, it wouldn’t. One percent higher inflation reduces the real debt by an extra 1% each year, but it would also raise nominal interest rates by 1% due to the Fisher effect. At best, you get a one-time gain from reducing the real value of the existing stock of debt, but those gains are reversed the next time you revert to 2% inflation. Many people who read Thorsten Slok’s recent comments on monetary and fiscal policy might erroneously infer that fiscal dominance is a bigger problem when the debt is primarily short-term:

Actually, the one-time gain from an unexpectedly inflationary monetary policy is greatest when the debt is mostly long-term bonds. Never reason from an interest rate change.

Under our current fiscal trajectory, we would eventually need much higher inflation to avoid default. But I very much doubt that Congress has the votes to tell the Fed to raise the inflation target to 5% or 10%. So how does Congress exert fiscal dominance? The President could appoint doves to the Fed, but after what happened to Biden, what president wants to be known for creating high inflation? (If Trump wants easy money the motivation would be economic growth—he couldn’t care less about long run fiscal sustainability, or anything else that occurs after he leaves office.)

So why is the Japanese yen currently so weak? In a word—China. Japan’s strength has been their ability to export manufactured goods such as cars and consumer electronics. Now they face competition from a rising power with 11 times their population, which can export many of those same goods at much lower prices. This is what explains the dramatic fall in Japan’s real exchange rate—not monetary policy.

Japan’s solid but not excessive NGDP growth and their low unemployment rate suggest that monetary policy is currently not the problem. Japan’s problems are structural. Back in the 1980s, who would have expected Japan to struggle so much in competing not just with China, but also with places like Taiwan and Korea. What are the Japanese versions of TSMC and Samsung? Why does Japan seem stuck with a 20th century economy?

Japan’s monetary policymakers have done all they can, now Japan’s policymakers need to figure out a way to make their economy more dynamic.

PS. Keynesian readers may be skeptical of claims about Japan made by a market monetarist. I suggest they look at Paul Krugman’s excellent 2018 paper on Abenomics, which reached similar conclusions.

More By This Author:

Core Nominal GDPThe Great Depression: Elevator pitch

David Beckworth On Fed Policy