Core Nominal GDP

Image Source: Pixabay

On average, financial markets respond to the monthly jobs report more dramatically than to any other piece of economic data. In this post, I’ll explain why.

Recall that macroeconomics mostly focuses on three issues: inflation, the business cycle, and long-run economic growth. The first two are largely determined by movements in nominal GDP, that is, by monetary policy. And just as there is headline inflation and core inflation, there is headline NGDP growth and core NGDP growth. Before considering core NGDP, let’s review the concept of core inflation.

Cynics argue that core inflation is a silly concept, as it ignores the prices that consumers care about the most—food and energy. That’s not a good argument, because core inflation is not used to measure consumer welfare; it’s used to ascertain the underlying trend in inflation. Because food and energy shocks tend to be transitory, it turns out that core inflation better predicts future headline inflation than does headline inflation itself.

I’d argue that a similar consideration applies to NGDP. Nominal wages are the most important part of NGDP, because the business cycle is mostly a product of unstable NGDP in a world where hourly nominal wages are sticky. Volatility in NGDP doesn’t have much impact on the business cycle unless it impacts the labor compensation part of NGDP, which is a bit more than half of the total. (A bit over a quarter is capital income, while the remainder is depreciation and indirect business taxes.)

Many people are confused by claims that recessions are caused by both sticky wages and unstable wages. Isn’t that a contradiction? To see why it isn’t, consider an economy where wages had been growing at 4% a year for a decade. Now assume that NGDP growth slows to 2%, due to a tight money policy. If hourly nominal wages are sticky—say at 4%/year—then growth in total labor compensation is likely to slow down more gradually than NGDP, perhaps to 3%/year. But that means profit growth will slow, especially abruptly, perhaps leading to a recession. Eventually, hourly wages begin falling, but at that point, they are too high.

The opposite pattern occurred in 2020-22, when a rapid acceleration in NGDP growth caused profits to rise more rapidly than the more sticky wage component of NGDP, leading to a tight labor market with high levels of employment. In either case, the stickiness of nominal wages results in NGDP shocks impacting total employment—what I call the musical chairs model.

(Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net). - Own work)

This is the part that people find confusing. During a recession, you get high unemployment because wages are too high, even though a recession is associated with gradually slowing wage growth. Thus, a tight money policy might cause equilibrium wage growth to slow from 4% to 2%, even as actual wage growth only slows from 4% to 3%, due to sticky wages. Paradoxically, wages become too high because of a policy that caused wage growth to slow.

The monthly jobs report (usually released on the first Friday of each month) provides three key labor market indicators:

-

Average hourly wages

-

Average weekly hours

-

Total payroll employment

If you combine the three, you get a rough estimate of the growth rate in total labor compensation. I think of that as “core NGDP”, the part of NGDP that is crucial for determining the business cycle. And whereas total NGDP is provided about four weeks after each quarter ends, this measure of “core NGDP” is provided just a few days after each month ends. That makes the jobs report the most timely indicator of current trends in NGDP growth.

There is much discussion of whether the Fed should care about the unemployment rate or focus exclusively on inflation. I don’t entirely agree with either side of the debate. Changes in total employment are one of three factors that affect total nominal wage growth (along with hourly wages and weekly hours.) While the Fed should not target the unemployment rate, a sudden rise in unemployment is usually an indicator of unstable NGDP growth, which will impact total labor compensation.

The best of all possible worlds would be stable NGDP growth and flexible wages. The second-best world would be stable NGDP growth and sticky hourly wages. The worst of all worlds would be unstable NGDP growth combined with sticky nominal wages. We cannot have the best of all possible worlds. So, let’s use monetary policy to aim for the second-best option—sticky wages and stable NGDP growth.

PS. If you’ve followed the logic of my argument, you will understand why the optimal policy would stabilize NGDP per capita, rather than total NGDP. The central problem in macroeconomics is sticky hourly wages.

PPS. Off topic: I read a recent Cowen/Tabarrok discussion of fiscal sustainability that was a bit sloppy with the facts:

TABARROK: If you look at taxes as a share of GDP, it has been between 17% and 20% for 50 years.

COWEN: Now it’s like 23%, isn’t it? 24%. It’s gone up permanently, yes.

TABARROK: I don’t think it’s that—not taxes. Spending has. Spending has. Actual taxes have not gone up as a share of GDP.

Alex is closer to the truth—it’s a bit below 17% of GDP. Facts matter! Trump is the one who put us onto an unsustainable path back in the late 2010s, when his tax cuts depressed tax revenue to a very low level. Some of the tax cuts might have been justified on efficiency grounds, but only if they’d been paid for with spending cuts. They were not.

TABARROK: Let’s turn to growth as a way of paying off the debt. Microsoft’s doing well, and AI’s doing well. Now, that should be raising real interest rates.

COWEN: Correct. It’s not.

TABARROK: It’s not.

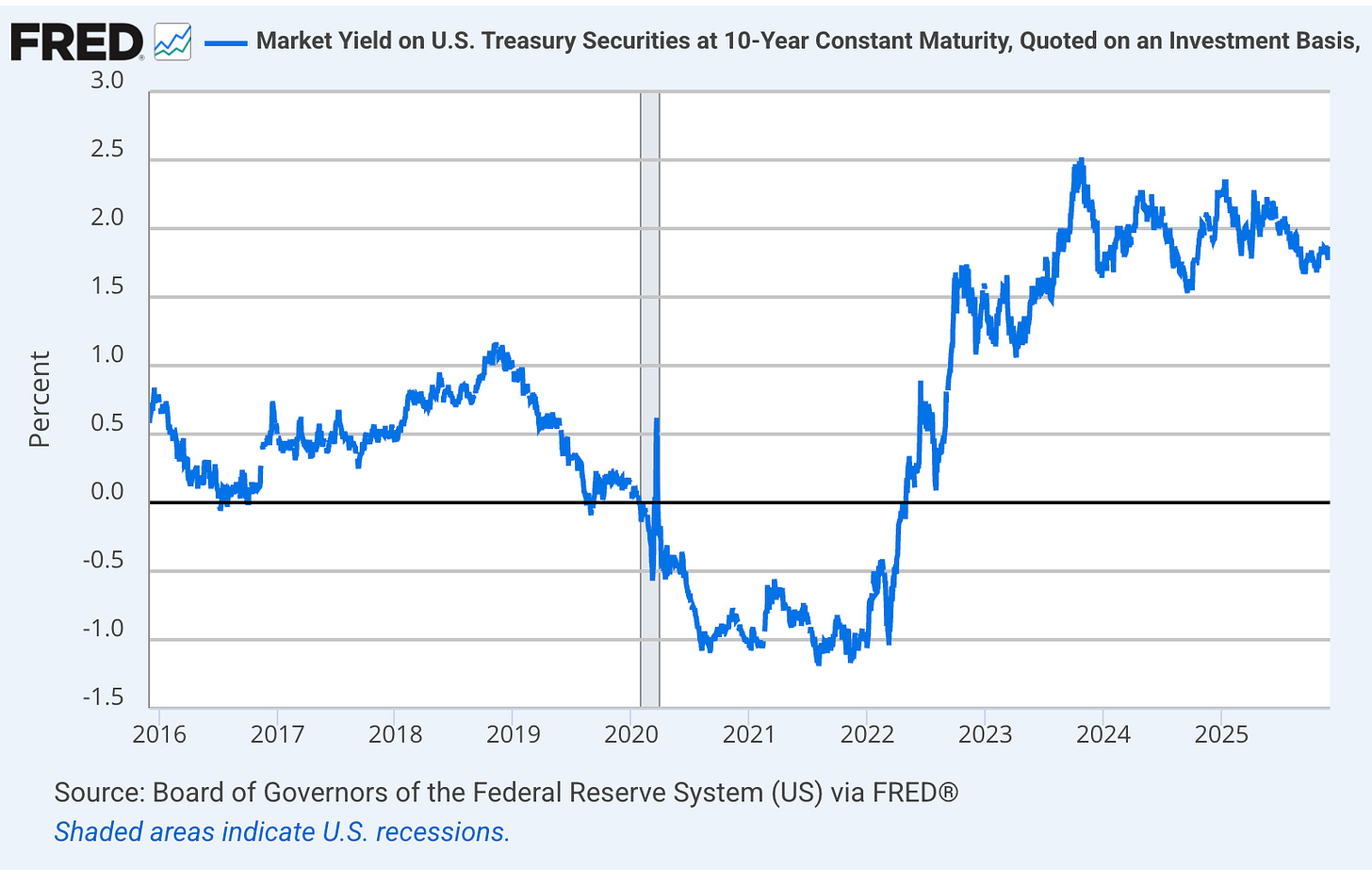

How can they both be so confident? This graph showing 10-year TIPS yields doesn’t prove that the AI boom is raising real interest rates (relative to the late 2010s), but it sure as heck doesn’t prove they are not raising real interest rates:

I agree with Tyler’s claim that tax increases are the most likely way the debt unsustainability issue will be resolved, which is the core issue that they examined. This could explain why markets are not currently forecasting high inflation. But I felt the discussion was a bit too sloppy with the relevant empirical data. People need to be made aware of the fact that the budget deficit became unsustainable at a specific moment in time—the late 2010s.

More By This Author:

The Great Depression: Elevator pitchDavid Beckworth On Fed Policy

What Caused The Great British Inflation?