Just How Vulnerable Is The Canadian Housing Market - Part 3

<< Read Part 1: Just How Vulnerable is the Canadian Housing Market

<< Read Part 2: Just How Vulnerable Is The Canadian Housing Market - Part 2

Image Source: Unsplash

Two previous blogs examined the Canadian housing market with respect to its sensitivity to changes in credit conditions and its ability to withstand a systemic drop in housing prices. This blog shifts to the issue of housing supply and the role it plays in driving up prices in the major Canadian cities. The blog draws extensively on a recent report by Scotiabank which attempts to estimate the housing supply shortage that continues to plague the Canadian market. (Estimating Housing Shortage).

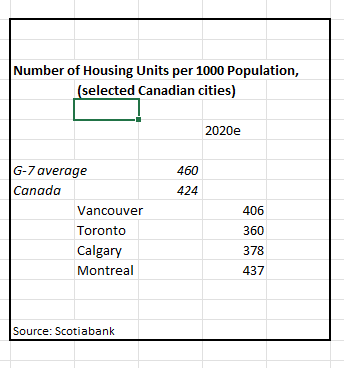

How does Canada compare to other G7 countries in providing housing? Housing supply is best examined by considering the construction of new housing units relative to changes in the population. Canada has the lowest number of housing units per 1,000 residents of any G7 country. Whereas the G7 countries average 460 housing units per 1000, Canada registered 424 units/1000 in 2020, slightly down from 427/1000 in 2016. Scotiabank estimates that Canada would need “an extra 100,000 dwellings ....to keep the ratio of housing units to population stable since 2016—leaving us still well below the G7 average”. As the accompanying chart points out, the shortfall in housing units/1000 population is more acute in the two major metropolitan areas, Vancouver and Toronto, where home prices have been increasing at rates of 20% annually since 2018. With the bulk of the 300,000 new immigrants to Canada moving into these two cities, developers have not been able to keep up with housing demand.

The Scotiabank report cities that the inelasticity of housing supply lies directly at the doorstep of the local authorities responsible for planning and the overall approval process. For example, a variety of development charges for new projects have been steadily rising. Consequently, the marginal cost of new projects compares unfavorably with investment returns on existing properties. Changes in provincial rent controls, in response to political pressures, have made it difficult for developers to determine rates of return necessary to warrant the risks taken. In addition, on the ground, the shortage of skilled workers makes it more difficult to bring projects in on time and on budget.

Readers have been inundated with news reports documenting how the pandemic has resulted in a major shift in the preference for greater living space, allowing for thousands of service workers to work from home. And, of course, there is no denying that negative real rates of interest make mortgages more affordable. However, the Scotiabank report argues that

“So, while it is clear that interest rates and a shift in preferences for housing by type and geography (facilitated by remote-work arrangements) contributed to the strength of the housing market, the fact remains that the principal challenge facing the housing market—and the underlying cause for rising prices and diminished affordability—is the substantial insufficiency of supply relative to demand”

In sum, given that supply conditions take a long time to turn favorably, we can expect that housing prices in Canada will continue to move up in the coming years.