Canada’s Labor Force Participation Rate Has Been Shrinking For Quite A While

Canada Clearly Needs More Immigration To Offset The Continued Slowing In Its Labour Force

“By 2030, all 9.2 million of Canada’s most prominent worker cohort—the baby boomers—will be of retirement age. This reality, in combination with a low fertility rate, is placing increasing economic and fiscal pressure on Canada. As such, Canada needs to identify solutions to replenish those exiting the workforce in order to maintain its high living standards.” (Conference Board of Canada, May 3, 2019).

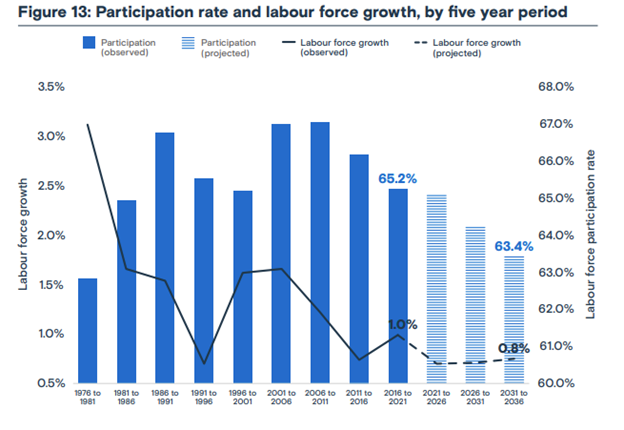

Canada’s labor force has been slowing for many years, and demographic changes are expected to impose further downward pressure on its growth in the coming years.

As a recent report by the Business Development Bank of Canada (September 2021) highlighted, the important reasons why we should expect a further decline in Canada’s labor force participation rate, and of course, a future slowing in the growth of the Canadian labor force.

The most important reason for expecting a future of further labor shortages is that Canada’s working-age population is aging as baby boomers exit the workforce and new entrants are unable to fill all the gaps.

The report also points out that retirements in Canada are expected to remain elevated until at least 2026, and that young people are spending longer on their education, which results in them delaying the start of their careers.

Finally, while immigration is a net positive to the Canadian economy and its workforce, it is not sufficient on its own to compensate for the other slower forces at work.

The pandemic made the labor shortage problem worse since it seems that the number of Canadian retirements has increased. They may have been planning to do so in two or three years but decided to move up the date because of the pandemic. As well, many Canadians who lost their jobs simply shifted to other sectors offering better pay and working conditions.

As well, the pandemic caused immigration to be reduced by roughly one-half in 2020 and 2021. That is, there were about 400,000 fewer immigrants arriving in Canada in 2020 and 2021 than was originally planned for

Canada’s labor shortage has been particularly hard on smaller businesses that have borne the brunt of the pandemic. Smaller firms experienced a series of shutdowns and faced serious financial challenges because of the pandemic. And now they are facing labor shortages as a post-pandemic economic recovery gathers steam.

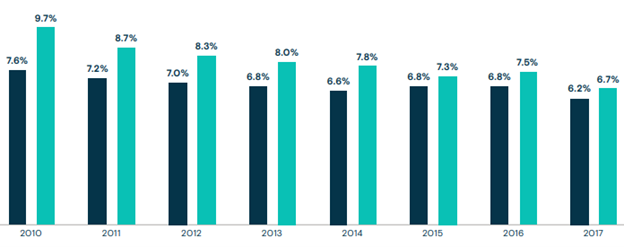

Returning to the issue of the need for increased immigration, the Business Council report indicates that the unemployment rate among new Canadians is higher than that among native-born Canadians, though the unemployment gap between the two groups has been shrinking in recent years as Canada’s job market tightened up.

An accompanying chart compares the unemployment rates for both groups since 2010.

Canada’s economy has always been dependent on immigration and in fact, about 22% of the Canadian population is foreign-born. So if Canada didn’t accept immigrants, its population would shrink due to the country’s low birth rate. In fact, since the 1970s Canada’s birthrate dropped below the threshold needed to maintain a steady population.

Without immigration, Canada’s labor force would shrink and the country's economic growth and standard of living would suffer. And while new immigrants into Canada add to the supply of labor, they also account for an increase in aggregate demand, which boosts overall purchasing power.

In sum, it seems rather likely that labor shortages in Canada will persist for several more years, and this will require major efforts to overcome them.

In other words, higher wages alone won't solve Canada's labor shortage problem.

The Unemployment Rates For Landed Immigrants Versus Canadian-Born Workers

Arthur

The last chart does not identify which group is which.

You are right. The new Canadians (green bar) have the higher unemployment rates in all cases.

You are right. The new Canadians (green bar) have the higher unemployment rates in all cases.