“Surging Dollar Stirs Markets Buzz Of A 1980s-Style Plaza Accord”

That’s the title of a Bloomberg article yesterday. Every few years, there’s talk about concerted action to weaken the dollar, as in 2015. There’s good reason to wish for a weaker dollar at various times — a strong dollar and high-interest rates strain emerging market external balances. But would such action matter? Here’s a look at the dollar and some covariates.

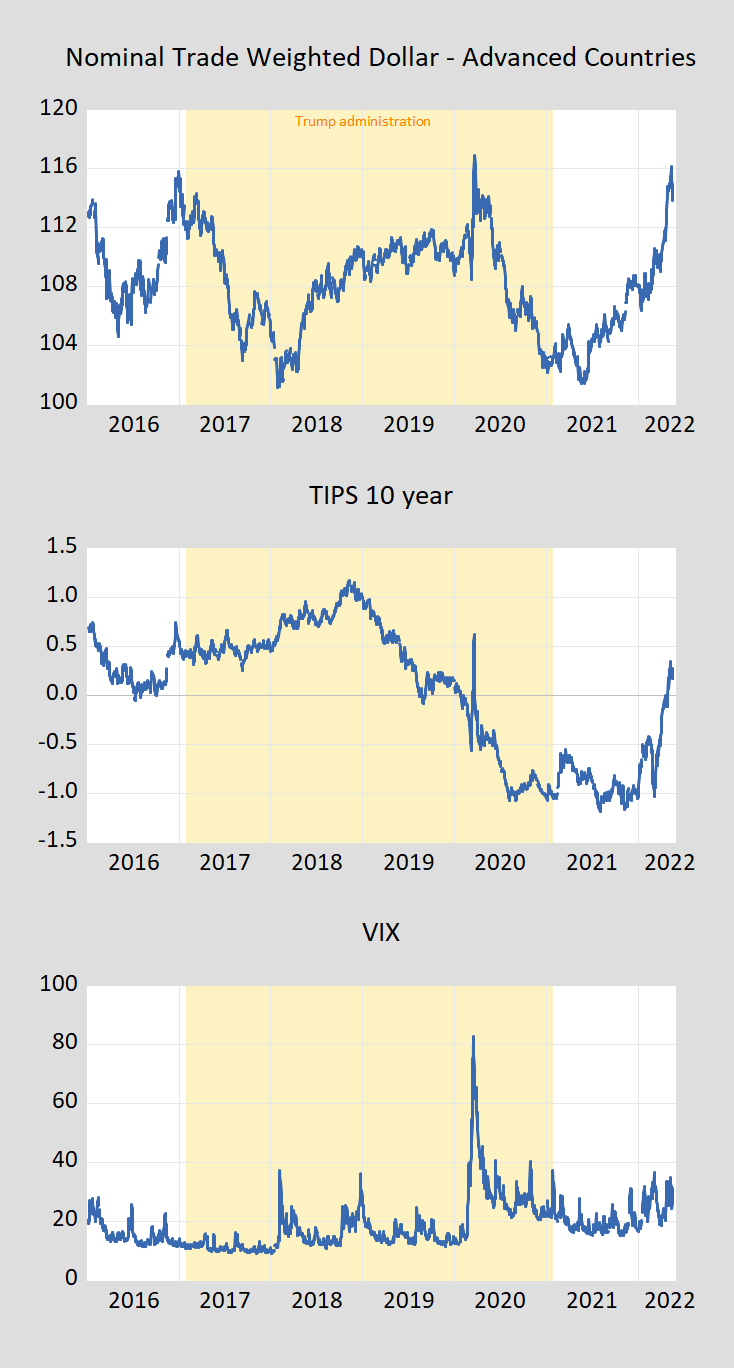

Figure 1, top panel: Nominal trade weighted dollar (vs. advanced economies); middle panel, TIPS 10 year yield, %; bottom panel, VIX. Light orange shading denotes Trump administration. Source: Federal Reserve, Treasury, CBOE via FRED.

Note that the current surge in dollar value is not tightly tied to the risk appetite, as measured by the VIX, but more so to the real interest rate, suggesting safe-haven factors are not the major driver of dollar strength. Figure 2 presents a detail of the graph.

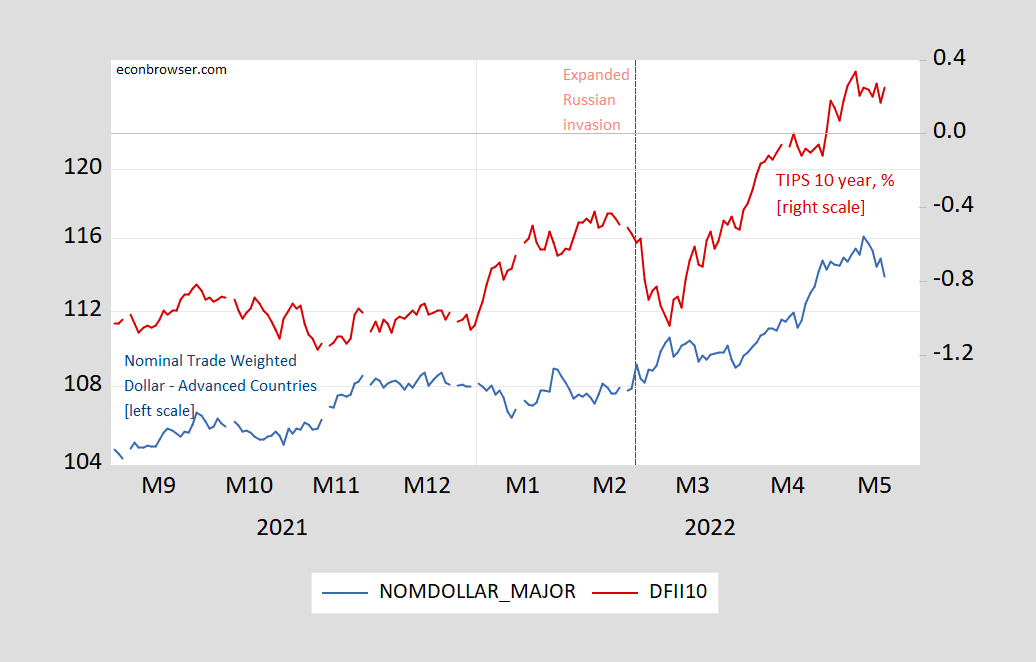

Figure 2, Nominal trade weighted dollar (blue, left log scale), TIPS 10 year yield, % (red, right scale). Last four days of exchange rate extrapolated using DXY. Source: Federal Reserve, Treasury via FRED, tradingeconomics.com, and author’s calculations.

There’s a long-running debate as to whether sterilized foreign exchange intervention — that is central bank buying and selling foreign currency while holding the money base constant — can influence the exchange rate. In earlier times (say pre-1990), the conventional answer was “no” (see description here). A few years ago, my view was that a relatively small intervention wouldn’t make much of a difference. More recent assessments, from both theoretical and empirical perspectives, are more nuanced. A recent comprehensive survey of the literature on foreign exchange intervention is Popper (2022).

The practice of central bank intervention for a time ran ahead of either compelling theoretical explanations of its use or persuasive empirical evidence of its effectiveness. Research accelerated when the emerging economy crises of the 1990s and the early 2000s brought fresh data in the form of urgent experimentation with intervention and related policies, and the financial crisis of 2008 propelled serious treatment of financial frictions into models of intervention.

Current intervention models combine financial frictions with relevant externalities: with the aggregate demand and pecuniary externalities that now inform macroeconomic models more broadly, and with the trade-related learning externalities that are particularly relevant for developing and emerging economies. These models characteristically allow for normative evaluation of the use of intervention, though most (but not all) do so from a single economy perspective.

Empirical advances reflect the advantages of more variation in the use of intervention, better data, and novel approaches to addressing simultaneity. Intervention is now widely seen as influencing exchange rates at least to some extent; and sustained one-sided intervention and its corresponding reserve accumulation appears to play a role in moderating exchange rate fluctuations, and in reducing the likelihood and damaging consequences of financial crises.

Key avenues for future research include sorting out which frictions and externalities matter most, and where intervention—and perhaps international cooperation—properly fits (if at all) into the blend of policies that might appropriately address the externalities.

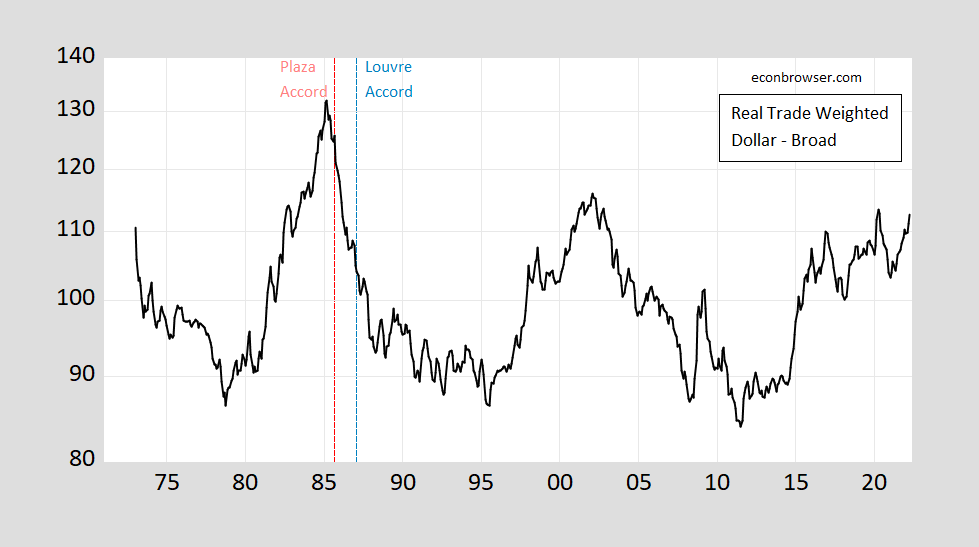

I’ve left out the question of whether the dollar is overvalued (for a discussion of what that means, see this post). What is true is that based on prices, the dollar is strong — although not as strong as in 2002, and certainly nowhere as strong as in 1985. (This is perhaps why this topic doesn’t show up on the agenda of the ongoing G-7 Finance Ministers meeting.)

Figure 2: Nominal trade weighted value of the US dollar against advanced economy currencies (black, log scale). Source: Federal Reserve via FRED.

Disclosure: None.