Which One Doesn't Belong?

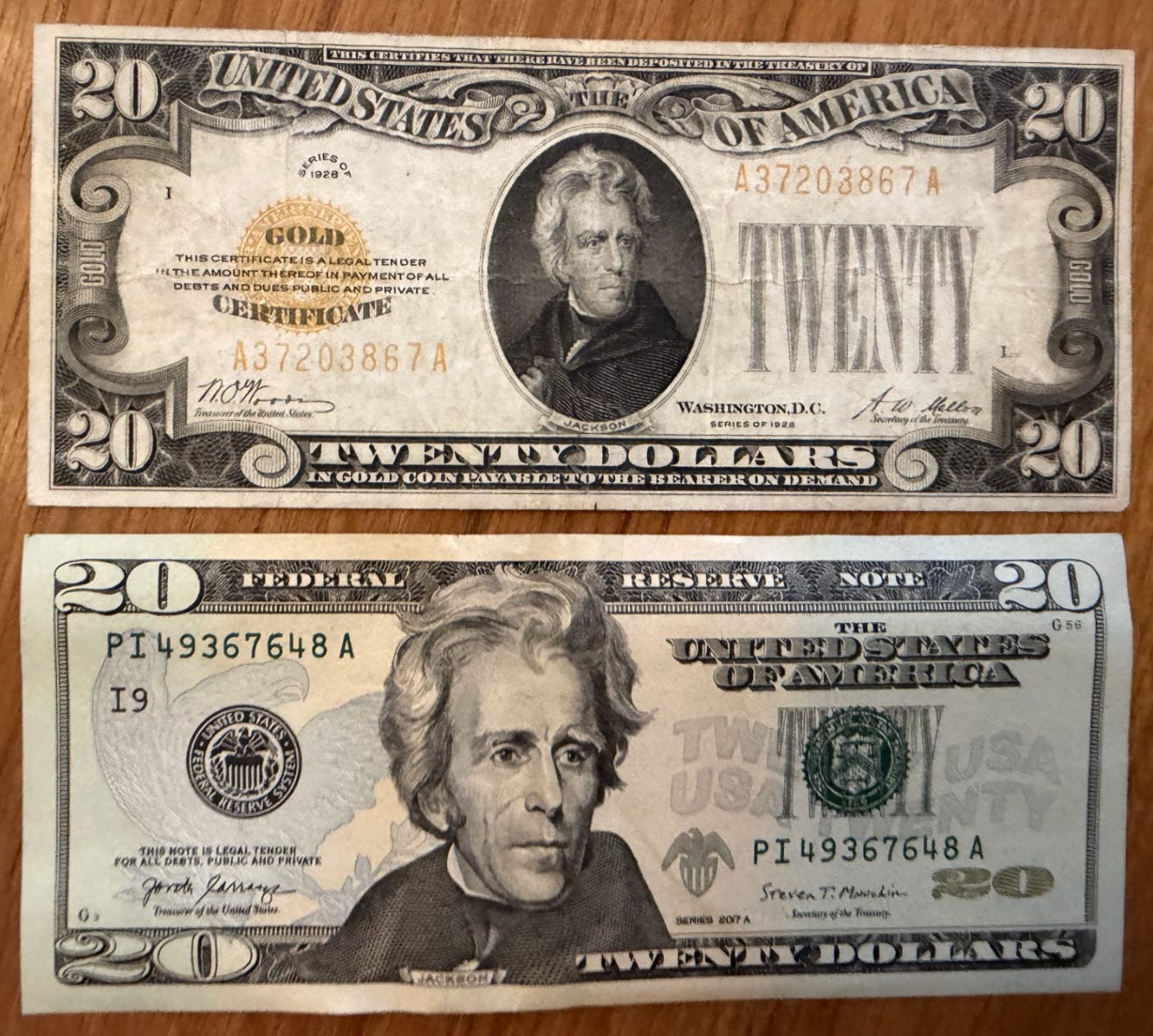

Here are two examples of US currency:

And some bitcoin:

Photo by Kanchanara on Unsplash

Which one doesn’t belong? Which type of money is the most distinct from the other two? The answer depends on which attribute you believe is the most important.

When I taught monetary theory, I used to pass around these two currency notes in class. At the time they looked almost identical, but Jackson’s head was enlarged in 1998, as you can see. That’s unfortunate, as previously they were a good example of how two objects that look quite similar could be radically different. The 1928 currency note could be redeemed at the Treasury for nearly an ounce of gold, now worth over $4000.

To better understand how Americans used to think about currency, consider an example of someone selling a used car and being paid with a personal check for $2500. The seller might take the check to the bank to see if it could be exchanged for some “real money”, i.e., currency. Similarly, back in 1928, the currency note was viewed as being sort of like a check, and the “real money” it could be exchanged for was gold. After 1934, however, it could no longer be exchanged for gold, as the federal government had defaulted on the obligation that was plainly printed on the front (bottom center):

TWENTY DOLLARS IN GOLD COIN PAYABLE TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND

Nonetheless, people continued to accept $20 bills in payment, even without gold backing. In retrospect, it is odd that it took so long for people to understand why fiat money might have value. When I was younger, I recall theories that currency had value because it could be used to pay taxes. But that sort of explanation is clearly not required, as bitcoin also has a positive value despite no commodity backing or utility in paying taxes. Instead, currency has value because it is useful:

-

It is convenient for making transactions (although its utility in this area is declining over time.)

-

It is a way of hiding wealth from authorities, where its role is increasing.

I have no ability to prediction the price of bitcoin, although in my very first post on the subject I suggested that it was not a bubble. At the time, the price was $32.

You’re welcome.

But I never bought any bitcoin, because my lack of belief in bubbles implies a low level of confidence in predicting asset prices. Nonetheless, I do believe it is possible to understand the fundamentals of asset prices, even if we cannot predict how those fundamentals evolve over time. (As an analogy, geologists understand the fundamental cause of earthquakes but cannot predict them.)

There are currently about 20 million bitcoin in circulation. Thus, a price of $90,000 per bitcoin implies a total market value of $1.8 trillion. In that case, you can think of the price of $90,000 as being determined by the fact that the aggregate market demand for bitcoin is currently about $1.8 trillion.

Today, there is roughly $2.4 trillion in US currency in circulation. You can think about the value of a single dollar bill (and hence the CPI) as being determined by two factors:

-

The total aggregate demand to hold US currency, in real terms.

-

The quantity of US currency.

You could see the price level rise 10% because the currency stock increases by 10% at a time when the public does not wish to hold more of its purchasing power in the form of currency. Or you might see the price level rise by 10% because the quantity of currency was unchanged at a time when the demand for currency fell by 10%. Or some combination of the two.

Bitcoin is an interesting type of money because its quantity is nearly fixed. (Technically it is asymptotically approaching a maximum quantity of 21 million.) That makes the determination of its value a conceptually simpler problem than determining the purchasing power of currency, as only the demand side of the bitcoin market shows significant volatility. This is similar to the sort of money supply rules once proposed by monetarists.

Nonetheless, it is far easier to predict changes in the value of US currency than changes in the value of bitcoin. That’s because while both the supply and demand for currency show significant changes over time, the Fed acts in such a way that changes in currency supply mostly accommodate changes in currency demand, leading to a situation where the purchasing power of currency depreciates at roughly 2%/year, at least most of the time (not in 2022!)

The Fed doesn’t directly target the currency stock. Rather they adjust the monetary base (via open market operations) and the interest rate (using IOER) in such a way that the currency stock grows on average about 2%/year faster than real currency demand.

So, which one doesn’t belong? In one sense, bitcoin is clearly the outlier. The other two currency notes pictured above are both examples of US dollars. They represent the same unit of account.

But in another sense it is the gold note that is the outlier among the three types of money. Back in 1928, gold was the medium of account in the US and in most other developed countries. The global price level was determined by the global supply and demand for gold. The currency stock was at least partly endogenous, which is why Canada’s currency stock fell sharply during the early 1930s. Canadians “needed” less currency in a world of sharply falling prices. The US currency stock did not decline (after 1930), because unlike Canada we had lots of bank failures that led to an increase demand for currency.

[If you are confused by terms like unit of account and medium of account, consider that in 1928 gold was the medium of account in both the US and Britain, but the two countries had different units of account (US dollars and British pounds.)]

Modern $20 bills and bitcoin are both examples of fiat money. They are not backed by any sort of real asset such as gold or silver, and their values are determined by a combination of “monetary policy” and private sector shocks to money demand.

Today, we also have stablecoins, which are generally backed by another asset such as fiat money, gold, or another cryptocurrency. Even if back by a fiat currency like the US dollar, I would regard stablecoins as more analogous to the old gold notes than to a modern fiat currency or bitcoin. The purchasing power of stablecoins is determined by the purchasing power of the underlying asset (plus a small default risk?), not the quantity of stablecoins

PS. Interestingly, the ratio of the CPI in January 1960 (29.3) to the CPI in January 1928 (17.3) is almost identical to the ratio of the official price of gold in 1960 ($35/ounce) to the price of gold in 1928 ($20.67/ounce.) This means that a person who converted $20.67 into an ounce of gold in 1928 and later sold it in Zurich in 1960, received back exactly the same purchasing power in dollars as the currency they sold in 1928, despite lots of dollar price inflation. (Gold bullion could not legally be sold in the US in 1960, which is why I assume a sale in Switzerland.)

I paid $70 for this $20 bill back in the 1980s, which my students found amusing. But it apparently is now worth about $300 to collectors on Ebay. If it could still be redeemed for gold today, it would be worth over $4000.

More By This Author:

The Nguyens And The Fed

13 Years Later: The Lessons Of Abenomics

Core Nominal GDP