Everything Is Broken

I was on a client call earlier this week with Steve Blumenthal. The gentleman is at that stage in life where he needs cash income and not risk. Steve commented, “The bond market is broken.” And indeed, the traditional fixed income bond market is broken, thanks to the Fed. We were able to suggest some alternatives (they are out there) that could help solve his problem.

But it got me thinking: "What else is broken?" And the more I thought, the more I realized that the data that we use every day, the very systems that we are forced to work with, are indeed in various stages of being broken.

There is a great scene in the fabulous movie The Princess Bride where the criminal “mastermind” Vizzini keeps uttering the word “inconceivable.” After the nth time, Inigo Montoya turns to him and says, “You keep using that word. I don’t think it means what you think it means.” Today we are going to look at data from the standpoint of Inigo Montoya. I don’t think that data means what you think it means. Indeed, much of the data in the way we use it is simply broken.

In a few weeks, I will do a letter on things that aren’t broken, which are in fact incredible. I am an optimist, but I’m also realistic. I am “long” on the human experiment. Government? Not so much. Our economic and financial systems are badly broken in multiple ways. Some of the cracks are enormous, maybe beyond anyone’s ability to repair. Step one is admitting they are broken.

Today I will describe several major breaks—some obvious, some not. I hope to help launch a conversation about fixing them. Let’s look at some broken things.

Broken Credit

People correctly describe compound interest as a kind of miracle, even the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” The miracle has another side, though. For you to receive the benefit, someone else must go into debt or take risk.

Debt isn’t necessarily bad. It can be wonderfully productive if it lets you acquire something (like education) that increases your income, or a durable asset like a home. It becomes potentially problematic when used for other purposes, as is often now the case.

Excess debt accumulates in part because the price of debt (interest rates) is increasingly artificial. Politically-appointed central bankers manipulate interest rates and credit terms in order to achieve desired admirable policy outcomes, like higher employment and economic growth. Elected officials create subsidy programs that encourage yet more borrowing. And while they can point to a link between low rates and their targets, they ignore or forget about some of the unintended consequences.

These well-intentioned efforts may help some people, but they have side effects. Borrowing costs are widely mispriced, bearing little connection to the actual risk of a given loan. This is unfair to both borrowers and lenders. They pay/receive too much or too little. It is the inevitable result when committees, instead of markets, set important prices.

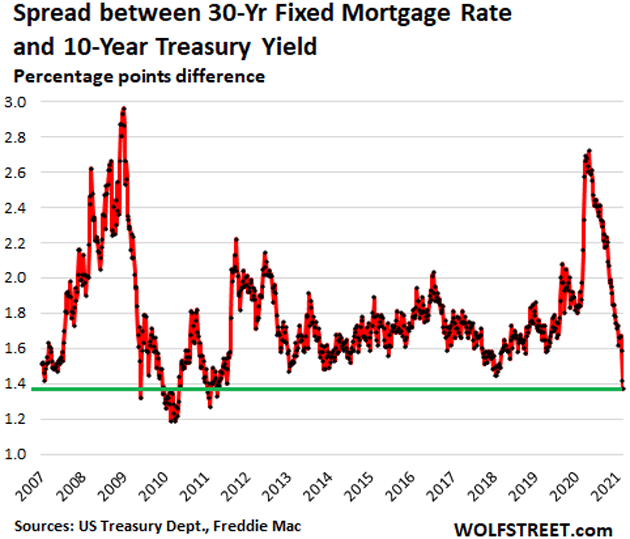

Here’s an example. This chart shows the spread between 10-year Treasury yields and 30-year mortgage rates.

Source: Wolf Richter

Obviously, lenders take more risk on mortgages than they do when buying Treasury bonds. We would thus expect mortgage rates to be higher, and they are. But does that risk really swing so wildly? Should it double, or fall by half, in only a few years’ time? Of course not. But that’s what happened, and there’s no mystery why. Mortgage spreads collapsed in 2009 and 2020 because the Federal Reserve bought truckloads of mortgage-backed securities.

Economic fundamentals didn’t do this. A committee decided to encourage home purchases and did so by making it cheaper to finance those purchases. The predictable result is a housing boom. Or, in the current case, amplification of a boom that was already happening for demographic and other reasons.

This has benefits. The construction activity creates jobs. Lower mortgage payments leave people more cash to spend on other things. But it also obscures reality. No one really knows what their home is worth. The same for many other asset classes, and for the loans underlying them. We don’t really have a bond “market” anymore. It broke long ago, and now we have a bond regime that exists outside the discipline of market forces.

I noted last week that the long-lost “bond vigilantes” are trying to rise from the dead. That is the way markets are supposed to work. I do not believe the Federal Reserve or other central banks will let them take control of the bond markets.

Peter Boockvar writes about what the Bank of Japan did yesterday:

"BoJ Governor Kuroda doesn't want any part of a further rise in yields and quashed any thoughts that he would widen the YCC range from the current level of 20 basis points from zero. He said, 'Personally I believe it's neither necessary nor appropriate to expand the band. There's no change in the importance of keeping the yield curve stable at a lower level.'

"Yields fell sharply in response with the 10-year down by 3.6 bps to just under 10 bps. It was 16 bps one week ago. The 40-year yield was down by 4 bps to .72% vs .82% one week ago. Again I'll say, they want higher inflation but then panic when rates go up. What they are now finally learning is the danger of what they wish for."

The same thing is happening in Europe and elsewhere. I firmly believe that at some point the Federal Reserve will begin to buy large quantities of longer-dated securities, taking interest rates down and driving a stake into the heart of those who want higher returns for the risks they are taking. That point is likely when the market drops (say) 20%. Until then they just let things rock along. The Federal Reserve is going to give us return-free risk.

Broken Retirement

I could call this section “Broken Dreams.” Millions of Baby Boomers are approaching what they thought would be a comfortable retirement age and instead finding they’re nowhere near ready. Worse, many believe themselves ready when in fact they aren’t. They will realize it only when markets show them what reality looks like.

The many reasons for this mostly trace back to the above-mentioned broken bond market. Retirement investing used to be easy. Save money, park it in interest-bearing instruments, and live off the income, with Social Security and maybe a job pension to help. Not complicated and it worked well for decades.

But about the time the oldest Boomers began reaching their mid-60's, this thing called “interest” mostly disappeared as committees and politicians decided to favor borrowers by keeping rates ultra-low. And just like that, retirement broke. The old method stopped working.

This left retirees and pre-retirees little choice but to “stretch for yield” in riskier assets. Indeed, that was the plan. The Federal Reserve under Bernanke, Yellen, and now Powell explicitly wants investors to take more risk. It’s the other side of their desire to encourage borrowing. This is also called “financial repression.”

So now we have retirees with far too much in stocks, junk bonds, or other risk-heavy assets. And not just individuals; the same is true for large pension funds. Their trustees are truly trapped: contractually obligated to pay certain benefits and unable to do so without robbing future beneficiaries.

I suspect my readers are more retirement-ready than most, but I still hear horror stories: people who worked hard, did their homework, made good decisions, only to see it all collapse. If you think you’re prepared, or already retired and think yourself secure, I suggest you reexamine your assumptions. Retirement is broken and your dreams could become nightmares.

Broken Stocks

What happens when you force investors into an asset class they don’t especially want or understand? Well, price comes from supply and demand. Artificially generated demand leads to artificially higher prices, and that is what we see in the stock market today. A survey in the year 2000 shows that investors expected future returns from the stock market would be 15% per year. I think current investors have similar expectations. They think stocks only go up, because the Fed will intervene if they don’t.

I reviewed stock valuations in more detail a few weeks ago (see here) and everything I said then still applies. Anyone who owns passive index funds will endure a major drawdown at some point. I can’t say exactly when, but it’s going to hurt. And who holds those funds? Investors who don’t really want to be in stocks in the first place and/or don’t understand the risks, or institutions that have little choice. Both categories are being forced by circumstances to make decisions they wouldn’t make in an otherwise “normal” market.

At the same time, managers of many listed companies aren’t making the greatest decisions, either. Many are responding to short-term incentives that encourage them to load up on debt, boost their share prices via buybacks, and profit by suppressing competition instead of innovating.

This is a stock market in which, much like bonds, prices bear little resemblance to fundamental reality. But more broadly, the equity markets are broken. I am all for making them accessible to everyone. Unfortunately, the regulatory and educational structure hasn’t kept up. So what we’ve really done is empower people to do risky things without preparing them for the consequences. It’s not going to end well.

Broken Data

Computer programmers used to talk about GIGO—Garbage In, Garbage Out. All the processing power in the world doesn’t help if it only processes flawed data. That explains some of our economic problems, too.

Just one example, although an important one, is the monthly US unemployment rate. According to the BLS it was 6.3% in January and, as we learned Friday morning, officially fell to 6.2% in February. 379,000 jobs were added, with 355,000 of them being in leisure and hospitality, as hotels and restaurants open back up. We are going to see a lot of large numbers like this in the coming months, which is a good thing.

However, no one I know thinks the unemployment number reflects reality. Even Jerome Powell believes it is deeply understated. He said so in a speech last month, which my friend Mish Shedlock quoted recently. Here’s Powell on Feb. 10:

"After rising to 14.8 percent in April of last year, the published unemployment rate has fallen relatively swiftly, reaching 6.3 percent in January. But published unemployment rates during COVID-19 have dramatically understated the deterioration in the labor market.

"Most importantly, the pandemic has led to the largest 12-month decline in labor force participation since at least 1948. Fear of the virus and the disappearance of employment opportunities in the sectors most affected by it, such as restaurants, hotels, and entertainment venues, have led many to withdraw from the workforce. At the same time, virtual schooling has forced many parents to leave the work force to provide all-day care for their children. All told, nearly 5 million people say the pandemic prevented them from looking for work in January.

"In addition, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that many unemployed individuals have been misclassified as employed. Correcting this misclassification and counting those who have left the labor force since last February as unemployed would boost the unemployment rate to close to 10 percent in January."

You count as “unemployed” if you actively look for work. Powell says, I think correctly, millions want to work but for various reasons haven’t been looking. So, they don’t count and the unemployment rate is artificially low.

This leads to more perversity. Imagine (as we all hope) vaccination progress brings the virus under control, hopefully soon. The economy should begin recovering as consumers gain confidence. Among those gaining confidence will be some of the millions presently out of the labor force. Once they start actively looking, the unemployment rate may well rise even though the economy is improving.

In other words, the unemployment rate is effectively useless, at least today, as an indicator of labor market conditions or economic growth. Yet we all keep breathlessly waiting for it every month. This is broken. We need better data so policymakers can make better decisions.

Broken Unemployment System

Economists and statisticians have known that something as seemingly simple as unemployment claims is filled with errors. My friend David Kotok (of Cumberland Advisors) wrote about an email exchange he had with our friend Philippa Dunne (of The Liscio Report), highlighting these problems. Some random quotes include:

"…Fraud that is understood to be happening ranges from lows of less than 4% of claims for some states up to an astounding 35% for the State of Michigan, which has had, historically speaking, a screening problem as much as a fraud problem."

"…Philippa wrote to me, 'So, I guess that’s what happens when you have a totally outdated system prone to failure. Legitimate people have a tough time, but organized crime has a field day.'"

"…Confirmed unemployment fraud in California now exceeds 11 billion claims, but there are more claims under review, so the actual figure may be considerably higher: 'In addition to the 10% of benefits confirmed to involve fraud, the state is investigating another 17% of benefits involving suspicious claims that have not yet been proven to be fraudulent—about $19 billion worth.'"

David went on for several pages in his usual meticulous way, providing dozens of links to the numerous problems in the unemployment claims world. Much of it appears to be organized identity theft that originates overseas. Elsewhere I read that there is the potential for $60 billion in total fraud.

One could be outraged for two reasons. First, any amount of fraud is unacceptable, much less this staggering amount. Second, as states try to deal with the fraud, they are less able to help legitimately unemployed people get the help they need and deserve. In a world where Google, Facebook, Amazon, and hundreds of others can track your random searches, where we have blockchains and artificial intelligence, it is no longer acceptable to have fraud in the unemployment claims process. The system is broken.

I could go on describing broken things for many more pages. I had a whole section on Broken Inflation, which affects everything but is completely wrong because of the way we measure housing prices. I decided that topic needs a fuller explanation so we’ll come back to it in another letter, maybe even next week.

I also want to talk about the way we measure inflation in the healthcare markets. Add that miscalculation in and we might be at 4% inflation right now. Today. And the Fed wants to keep interest rates low. The markets react to inflation numbers, unemployment numbers, and so on. But the numbers are broken. This will not end well.

Let me mention something that’s changed but isn’t broken: the Mauldin Economics Strategic Investment Conference. This year’s online SIC—being held on five ...

more

Unemployment is best reflected in the percentage of people not working maybe minus those in retirement. I think everyone agrees the governments unemployment numbers are so manipulated they have no relevance in any logical system at figuring out the truth. They are purposefully designed to provide false answers.

How so?

They calculate people filing for unemployment which has been manipulated by trying to find reasons to cancel benefits and lower the time people may be on them. Also it doesn't fully deal with those who are underemployed or do not qualify for unemployment mostly due to the fact they can't find a job for over a year.