10-Year Yields And Implications

Interest rates have been unusually stable since 2009. Some important global interest rate trends have emerged during the pandemic. Inflation expectations still remain a key determinant of bond yields.

The pandemic recession and the measures taken to spur economic recovery from the pandemic have resulted in some clear country differences in terms of short-term interest rates and bond yields.

Indeed, there have been three important interest rate developments associated with the pandemic recession that has shaped global interest rates as well as inflation expectations. Nonetheless, in all three cases, the interest rate patterns that are focused on here actually emerged before the pandemic.

The three important financial developments are (1) close to zero and in some cases negative central bank policy interest rates; (2) the fact that in the advanced economies the policy framework has deliberately supported extremely low and in some cases negative bond yields (e.g., ten-year yields), and finally; (3) an increase of the spread between higher bond yields of the emerging market countries compared to the advanced economies.

In the latter case, the large interest rate spreads clearly reflect the substantial differences in the inflation rates between the advanced and the emerging market economies.

Central banks turned to zero interest rates to protect their economies from the Great Recession in 2008-09. Ever since then, with some exceptions, we have been experiencing unusually stable and relatively low interest rates right across the yield curve.

Indeed, to save most of the developed world from a worsening economic downturn, since 2009 massive government deficits, close to zero central bank policy rates and extremely low bond yields have become almost the norm.

Even though short-term interest rates among the wealthy G7 countries are still quite close to zero, the comparable rates in the large emerging market countries are considerably higher. As an aside, in recent years, several European and Asian central banks have imposed negative interest rates on commercial banks which have also resulted in negative ten-year bond yields.

At first glance, negative interest rates seem almost counterintuitive. Why would a lender be willing to pay someone to borrow money, considering that the lender is the one accepting the risk of loan default?

The usual explanation is that central banks impose negative interest rates when they fear their national economies could slip into a deflationary spiral, where spending and investing is discouraged. In other words, the idea behind negative rates is to incentivize lending by the banks and spending by consumers, rather than saving and hoarding.

Some of these themes are explored in the accompanying four charts created by Yardeni.com.

As the first chart shows, comparing the benchmark policy rates of the three largest central banks in the G7, the US Fed is the only one with a policy rate barely above zero. (i.e., 0.13). The Bank of Japan’s overnight rate is -0.06, while the ECB equivalent benchmark interest rate is -0.50.

Then focusing on government bond yields (Chart 2), Germany’s ten-year bond yields are negative (-0.45) and Japan’s ten-year yield is barely positive at 0.08. The US government’s ten-year yield is the highest at about 1.5%.

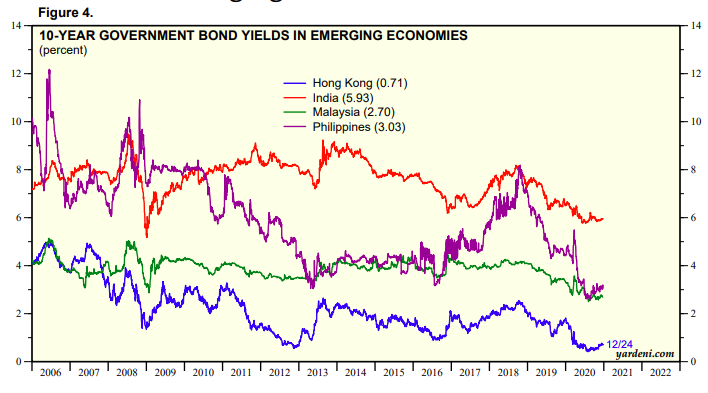

The third important trend is that the 10-year government bond yields of emerging market economies are considerably higher than the advanced countries. For example, as Chart 3 illustrates, India’s bond yield is 5.93%, the Philippines 3.03%, and Malaysia’s 2.7%.

Finally, as the data in Chart 4 highlights, the huge difference in longer-term yields between the emerging and the advanced economies clearly reflects significant differences in inflation and inflationary expectations.

That is, inflation in the emerging economies spiked dramatically during the pandemic, while there was no corresponding major spike among the advanced economies. Though up-to-date comparisons are difficult, the figures in chart 4 also indicate an average inflation rate in the emerging economies of close to 7% compared to a 1.6% inflation rate for the advanced economies.

Clearly, the major central banks understand that they will soon need to return to a more normal monetary posture. And as central banks start tapering back on government bond purchases, they will want to accomplish monetary normalization without exacerbating a sell-off in the bond market.

In other words, in the not-too-distant future, 10-year US bond yields will have to increase, perhaps by as much as 200 basis points by next year. This implies that the yield curve will steepen as the 10 and 30-year yields climb, while the Fed attempts to keep short rates as low as possible.

In closing, while the recent spike in inflation may not be seen as a longer-term problem for the economy, nonetheless inflation is clearly the most important determinant of nominal interest rates and bond yields. At present, the financial markets seem to be shrugging off the recent spike in US inflation, apparently accepting the Fed’s argument that it is only transitory.

This writer concurs with the Fed’s view that the inflation spike is only temporary. I also do not see an early return to the unhappy, high inflation rate experiences of the 1960s and 1970s.

Chart 1 Benchmark Central Bank Interest Rates

Chart 2 Ten Year Bond Yields, Major Countries

Chart 3 Emerging Market Country Bond Yields

Chart 4 Global Inflation Rates

Arthur

If long rates were to move up 200bps the impact would be very damaging. Since the investment grade corporate bond spreads are very narrow--approx. 150 pbs, that market would be severely impacted and this would lead to a dramatic sell off in the equity markets. The equity, corporate and govt bond markets are vey intricately tied. A 200pbs move on the 10 yr would mean that 10 yr interest costs more than double and would be very bad for housing and all sectors relying on capital investment. It would kill any nascent recovery.

The Fed will not allow this to happen. It will, as Japan does, introduce yield curve control (YCC) and bring down long rate through selective bond buying. We have had negative real yields for more than a decade and too much of the economy relies on that being maintained. I would not go short on the bonds for this reason.