Who Really Sets Interest Rates

With so much attention focussed on the Fed‘s rate setting decisions, investors often ignore who actually sets the whole array of interest rates that affect investment decisions. The persistence of low interest rates preceded the 2008 financial crisis, as investors witnessed a steady drop in nominal and real interest rates, starting in the late 1980s. Ben Bernanke while chairman made the case that rates were coming down in response to a glut in worldwide savings. He pointed the finger at Asian nations, in particular, as the main countries contributing to a worldwide savings glut which reached unprecedented levels by 2007. Some analysts go so far as to argue that excess savings found its way into the US mortgage market and contributed to its crash. But what has happened to savings rates since the crisis and what does it mean for future interest rates?

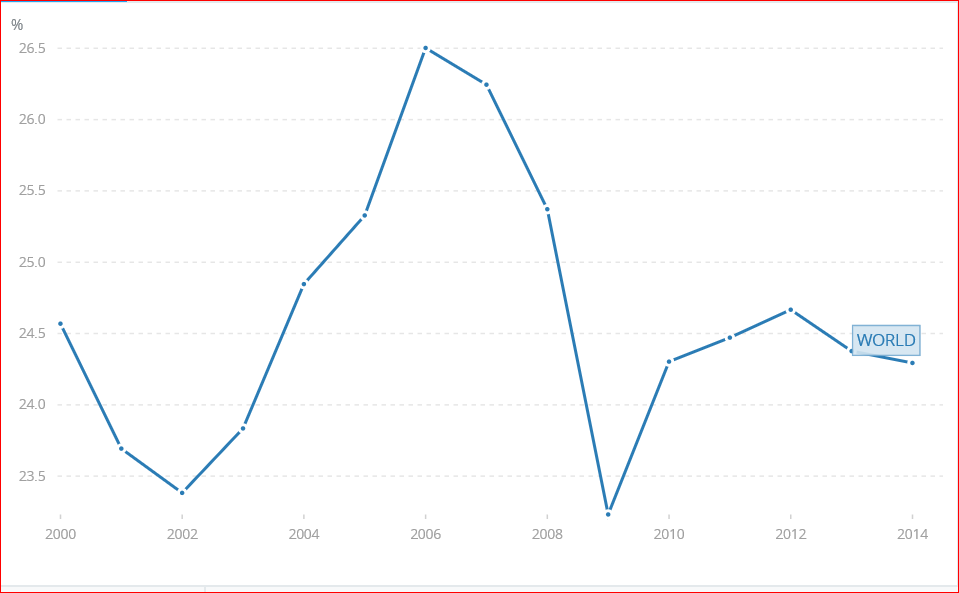

To begin with, let’s look at the savings rates in major regions today. Globally, the savings rate hit a high water mark in 2006, registering 26.5 percent of world output. (Chart 1). The rate dropped dramatically during the 2008 crisis, as massive deleveraging caused investors and nations to reduce debt and save less as a means of coping with the severe decline in asset prices.

Chart 1 World Savings Rate (2000-2014)

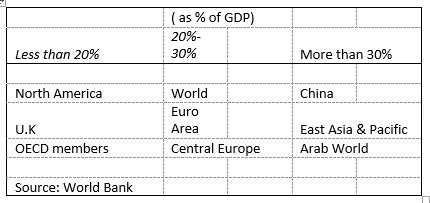

Since 2008 the savings rate has made a comeback and now measure just under 25 percent, still significantly high. Turning to individual regions, (Table 1), it is evident that Asian nations remain the most significant source of world savings, averaging around 35 percent of GDP. European nations save approximately 25 per cent of national income, while North America remains at less than 20 per cent. The rebound in regional savings rates continues to have a profound effect on interest rates, especially in the long end of the yield curve.

Table 1 Regional Savings Rates, 2014

A good measure of the impact of savings on long term interest rates is the inflation-indexed bonds. These bonds approximate what the market believes is the real rate of interest. ( Chart 2). U.S. inflation-indexed bonds have fallen in yield from just over 2 per cent in 2006-7 to approximately 0.25 per cent today. Given that nominal 10 –year rates are at 1.75 per cent, investors are anticipating that inflation will not exceed 1.50 per cent annually over the next 10 years---a very low inflation environment will likely dominate throughout the period.

Chart 2 10 –year Treasury Inflation-indexed Bonds

Clearly, as excess savings finds its way into sovereign bond markets, we anticipate long term rates to remain quite low. This is especially true in the Eurozone where long term real rates are negative. But excess savings is not the only reason that long term rates are under pressure.

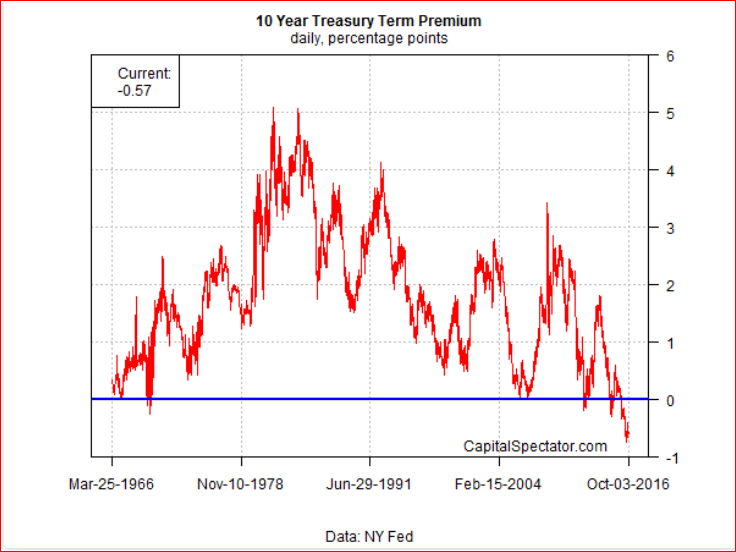

Another underlying feature of the decline in long rates is the virtual disappearance of the “term premium”. The term premium is an estimate of the additional compensation an investor needs to coax him/her to buy long dated bonds. Today, as Chart 3 shows, this premium is believed to be negative, a level achieved only twice in the last 50 years.

Chart 3 10-Year Treasury Term Premium

Granted, the premium is not directly observable, but is considered to be a indication of sentiment regarding the outlook for inflation, changes in monetary policy and a general willingness to hold onto bonds until maturity. In short, there is a certain degree of comfort that the Fed cannot generate conditions that would require a risk premium--- that would only come about if inflation and growth took off.

Are there any changes in the wind that will pressure rates to go up?

We know for certain that the savings rates are not about to fall. China continues to run up large current account surpluses and thus still has to send funds overseas. Its 40 per cent savings rates will continue to be felt in all debt markets in the rich countries, such as the U.S. and U.K. that run current account deficits and need external financing to balance the accounts. An aging population, especially in developed countries, will generate growing savings to pay for longer term retirement. Finally, there are those who suggest that secular stagnation, featuring low productivity growth, will put a lid on far long term rates can rise.

This must be what #Yellen says when she says #inflation will run hot. Lol, hot compared to temps on the darkside of the moon isn't that hot.

Sadly the US savings rate, despite Fed and others saying we save too much, is not that high. And sadly, like capitalism has always dictated, those who save and put money into capital investment end up the long term winners. It is unfortunate Fed policy encourages the exact opposite behavior from that which will keep us as long term global winners.