Higher For Longer

This will be my last letter of 2022. I want to use this letter as a set-up for my annual forecast issue the first week of January. That means we will touch on a variety of topics, kind of a snapshot into where my mind is today. Get ready to travel the world but let’s start at home with the Federal Reserve meeting this week.

Image via Mauldin Economics

Powell: Higher for Longer than You Can Imagine

There is this constant argument that Jerome Powell (can I call you Jay?) is somehow going to pause after the next rate hike, and then begin to cut rates in the late spring or summer because the economy will soften and inflation will have returned to the Fed’s target range. Bottom line up front: I think that view is completely wrongheaded.

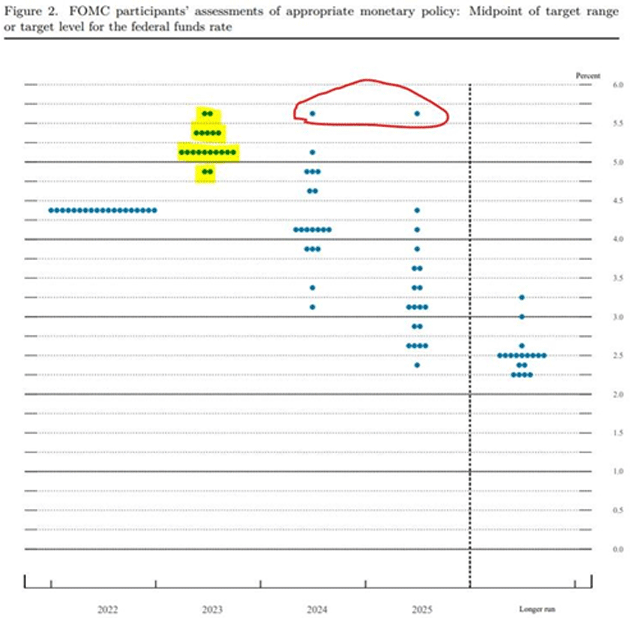

I am sure that you have seen the various versions of the “dot plot,” the anonymized chart of where all the regional Fed presidents and board members believe rates will be in the future. It is a good place to start our analysis. I am going to use one from Sam Rines because his has some rather appropriate humor in it. Note he highlights the predictions for 2023 and then circles the two highest rate predictions in 2024 and 2025. He quipped: “a Xmas tree … and we see you Bullard.”

Source: Samuel Rines

Takeaways:

- Rates will be higher for longer. The median Fed funds rate is expected to average 5.1% in 2023! That is nowhere near expectations and, if the dot plot is right, is off by at least (estimating) 40‒50 basis points.

- The consensus shows rates dropping to 4% in 2024. I see the longer-term “guesses” and that is just what they are. That is too long into the future to have anything more than cursory predictive value.

Let’s look at an analysis from Danielle DiMartino Booth at Quill Intelligence. I think this is spot on.

“[That brings us to] Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s comportment behind the podium Wednesday afternoon. As hard as the press pool tried to incite his ire, they never managed to goad him into losing his temper. That said, I’m not so sure polite Powell wasn’t worse than “Make My Day Jay.” Consider the following excerpt from the transcript in answer to whether he would consider raising the inflation target a la scared witless Europeans (the bolding is my own):

“'Changing our inflation goal is just something we’re not—we’re not thinking about and it’s not something we're going to think about. It’s—it—we have a two percent inflation goal, and we'll use our tools to get inflation back to two percent. I think this isn’t the time to be thinking about that. I mean there may be a longer-run project at some point but that is not where we are at all. The committee—we’re not considering that, we’re not going to consider that under any circumstances. We’re going to—we’re going to keep our inflation target at two percent and we're going to use our tools to get inflation back to two percent.’”

I sat in a room about 7‒8 years ago (if my memory serves). There was a four-person panel of very influential economists. Two had Nobel laurels. The other two were and are very prominent analysts of Fed policy. (Chatham House rules so I can’t reveal names.)

They were arguing for a minimum of a 3% inflation target and two (including one of the Nobel laureates) wanted 4%. Bill Ackman came out this week and said the Fed will have to change to a 3% target as reaching 2% will be difficult (duh!) and cause too much pain (my interpretation).

Two points:

- There is a quiet conversation in upper academic and economic policy levels that looks at the debt and thinks 4% inflation is what we need. This of course will slow the economy down but what if we are going to run deficits? They were worried back then US government debt was getting too high. Since debt is nominal, 4% inflation cuts it in half in 18 years. It also cuts your assets and income by half in that same time. They didn’t seem worried by the effect on middle America. They were trying to figure out how to kick the can down the road rather than balance budgets, which they felt would be too restrictive to the economy. Uber Keynesians all of them. Note that all of the Fed types seem to be Keynesians.

- Getting back to 2% inflation will be tough. The cost of goods is falling as supply chains get fixed, which helps. But wages are rising as are other service costs. Powell knows that he has to break that inflation expectation spiral and the only way is to do what Volcker did, or a 2022‒23 version of it. We don’t get to drop rates 20% over 40 years.

Higher wages will reduce productivity (cost of production versus output) and thus GDP. That is inherently inflationary. Breaking that almost requires higher unemployment, which Powell in his press conference clearly stated he was willing to allow. First order of business is to beat inflation. Then jobs. As harsh as that sounds, it is the correct thing to do today. (Note that I have been writing for almost two years now they should have been raising rates and cutting QE in late 2020-early 2021. They obviously missed that window and now we are where we are. They must force a recession and higher unemployment.)

Inflation is also a drag on employment and the economy. Find me an economy that flourishes under high inflation for a long time. Falling inflation starting from a high point? Yes. But not rising or staying high. Powell and now the rest of the FOMC seem to be on board with the #1 job being crushing inflation. That means higher for longer.

Sea Change

One of my favorite analysts is Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital. I read his quarterly letters quasi-religiously, generally 2‒3 times or more. His latest is one of his best. I am going to summarize a little and quote some, but you can read the full letter here. Let’s jump in:

“Sea change (idiom): a complete transformation, a radical change of direction in attitude, goals… (Grammarist)

“In my 53 years in the investment world, I’ve seen a number of economic cycles, pendulum swings, manias and panics, bubbles and crashes, but I remember only two real sea changes. I think we may be in the midst of a third one today.”

The first change he vividly describes was the creation of high-yield bonds and an increased appetite for balanced risk. Prior to Milken, et al., bonds rated below B weren’t considered investable. The only way a company could acquire another company was for cash or by borrowing, but borrowing was limited to the amount you could get without changing your rating.

With the advent of high-yield bonds, leverage became available to boost asset prices and capital investment, balanced by higher interest rates to offset the additional risk. This created a monster new wave of investment and what became “financialization” of the markets.

The second sea change was Volcker’s breaking of inflation and then the beginning of a 40-year bond bull market. Ever-lower rates coupled with increasing availability of funds created two massive tailwinds for the greatest stock and bond bull markets in history. If you borrowed at 10% and then a year or so later prime was 8%, you could refinance and lower costs, increase leverage, or both. Stocks, homes, real estate, private businesses, a host of enterprises all rose in value.

But that brings us to where we were in 2020. Quoting Howard Marks again:

“For what felt like eons—from October 2012 to February 2020 – my standard presentation was titled ‘Investing in a Low Return World,’ because that’s what our circumstances were. With the prospective returns on many asset classes—especially credit—at all-time lows, I enumerated the principal options available to investors:

• invest as you previously have, and accept that your returns will be lower than they used to be;

• reduce risk to prepare for a market correction, and accept a return that is lower still;

• go to cash and earn a return of zero, hoping the market will decline and thus offer higher returns (and do it soon); or

• ramp up your risk in pursuit of higher returns.

“Each of these choices had serious flaws, and there’s a good reason for that. By definition, it’s hard to achieve good returns dependably and safely in a low-return world.

“…The overall period from 2009 through 2021 (with the exception of a few months in 2020) was one in which optimism prevailed among investors and worry was minimal. Low inflation allowed central bankers to maintain generous monetary policies. These were golden times for corporations and owners thanks to good economic growth, cheap and easily accessible capital, and freedom from distress.

“This was an asset owner’s market and a borrower’s market. With the risk-free rate at zero, fear of loss absent, and people eager to make risky investments, it was a frustrating period for lenders and bargain hunters.” (Emphasis in original)

Then he gives us a tour de force analysis of where we are and how we got here. I highly suggest you read it but the conclusion is we’re not going back to ultra-low rates, barring a severe recession.

“The progression of events described above caused pessimism to take over from optimism. The market characterized by easy money and upbeat borrowers and asset owners disappeared; now lenders and buyers held better cards. Credit investors became able to demand higher returns and better creditor protections. The list of candidates for distress—loans and bonds offering yield spreads of more than 1,000 basis points over Treasuries—grew from dozens to hundreds.

“How has this change manifested itself in investment options? Here’s one example: In the low-return world of just one year ago, high-yield bonds offered yields of 4‒5%. A lot of issuance was at yields in the 3s, and at least one new bond came to the market with a “handle” of 2. The usefulness of these bonds for institutions needing returns of 6 or 7% was quite limited. Today these securities yield roughly 8%, meaning even after allowing for some defaults, they’re likely to deliver equity-like returns, sourced from contractual cash flows on public securities. Credit instruments of all kinds are potentially poised to deliver performance that can help investors accomplish their goals.”

The End of Financial Repression?

Let’s pause to think about that. Financial repression by central banks all over the developed world forced retirees, pension funds, endowments, etc. to take increased risks or miss their investment targets. Those targets were made in a “normal” economic environment and never changed when the Fed simply eviscerated whatever we thought of as normal. It was called the “New Normal,” and then as things progressed, the “New, New Normal” and it spiraled down from there.

Now, an investor can make better returns but must deal with inflation. This is just one opinion, and subject to being massively wrong, but I think Jay Powell (and maybe some others) realize the havoc they have created and want to get us back to a place where investors can earn real returns in a much-enhanced risk environment.

But that means inflation has to fall to his 2% target (I would prefer lower, but then I am an old curmudgeon) and interest rates have to remain higher than inflation, giving investors an opportunity to make at least modest real returns.

As long as Powell is chair, I don’t think rates are going back anywhere near the zero bound, nor should we.

Finally from Howard Marks:

“What we do know is that inflation and interest rates are higher today than they’ve been for 40 and 13 years, respectively. No one knows how long the… [the current economic situation] …will continue to accurately describe the environment. They’ll [the Fed] be influenced by economic growth, inflation, and interest rates, as well as exogenous events, all of which are unpredictable…

“As I’ve written many times about the economy and markets, we never know where we’re going, but we ought to know where we are. The bottom line for me is that, in many ways, conditions at this moment are overwhelmingly different from—and mostly less favorable than—those of the post-GFC climate described above. These changes may be long-lasting, or they may wear off over time. But in my view, we’re unlikely to quickly see the same optimism and ease that marked the post-GFC period.

“We’ve gone from the low-return world of 2009‒21 to a full-return world, and it may become more so in the near term. Investors can now potentially get solid returns from credit instruments, meaning they no longer have to rely as heavily on riskier investments to achieve their overall return targets. Lenders and bargain hunters face much better prospects in this changed environment than they did in 2009‒21.

“And importantly, if you grant that the environment is and may continue to be very different from what it was over the last 13 years—and most of the last 40 years—it should follow that the investment strategies that worked best over those periods may not be the ones that outperform in the years ahead.

“That’s the sea change I’m talking about.”

It’s Not Just the US

The publisher of Mauldin Economics, Ed D’Agostino, has started doing a regular video interview podcast, and he is really good at it and is getting marvelous people agreeing to come on his show. It’s free and you should subscribe. I will close this letter with a summary of part of his recent interview with Felix Zulauf as it focuses on the international scene. Here’s a link to the full video for those who prefer to watch/listen.

The world is splitting in two. The West, led by the US, and the autocrats, led by China. This will permanently impact supply chains and is long-term inflationary. The Saudis are moving to China’s camp.

In 2000, the US was the top trading partner for most of the world. Today that has completely flipped, with China being the top trading partner for all but North America, part of Europe (not all) and a few South American nations. In terms of trade, the globe has flipped from blue (US) to red (China).

The Biden administration made an error in weaponizing the US dollar and the global payment system. That will force non-US investors and nations to diversify their holdings outside of the traditional safe haven of the US.

We are in a war economy, where goods are frequently not available on demand and substitutions may be necessary. US consumers have not adjusted to this reality. The global economy faces structural challenges today. Too much debt and bond markets are rejecting actions that increase debt (UK gilt market as an example).

The US will see a mild recession in 2023. The UK and eurozone will endure a severe recession. China is already in a severe recession. Felix likens China today to Japan in the ‘90s. They had an over-expansion of credit and now have a broken financial system that will take at least a decade to resolve. The COVID lockdowns are merely camouflage to hide China’s economic weakness.

The next 10 years will see a roller coaster in the stock markets combined with serious geopolitical tension and conflict. Investors will need to be tactical—buy and hold will disappoint.

In the near term (Q1 2023), we may see new market lows due to earnings disappointments. Bond yields will rise. Inflation will drop as companies unload a glut of inventory in the global supply chain.

The sun will rise. The system will reset.

More By This Author:

Recession Scale

A Decade Of Roller Coaster Markets

The Economy Is A-Changin’

Disclaimer:The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more