The Economy Is A-Changin’

Then you better start swimmin'

Or you'll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin'

—Bob Dylan, "The Times They Are A-Changin"

Change is constant, in the economy and everything else. We talk about it often. Yet when we talk about the economy changing, we usually mean the economy’s condition is changing—from expansion to recession, deflationary to inflationary, emerging to developing, etc. That’s different from changes in the economy’s actual structure.

Yet I think that’s where we are. The “new economy” we’ll face as the 2020s unfold won’t just be a more intense version of the old one. It will be fundamentally different—profound, irreversible, and rapid evolution beyond anyone’s ability to resist.

We criticize Federal Reserve officials, and rightly so because they created many of our problems. Ditto for politicians. But as powerful as they are, central banks and governments still have limits. They can incentivize behavior, but they can’t always control it.

Bob Dylan wrote “The Times They Are A-Changin’” in 1963, hoping it would become a protest song, the anthem of a social movement. Movement toward what? Not the Vietnam War, which was still brewing at that point. He later said he was thinking more of the civil rights movement. But then the Kennedy assassination happened, LBJ expanded the war, anti-draft protests erupted, and the song acquired new meaning.

This is important to note. We can know (perhaps with Dylan it was more “feel”) change is coming without knowing the particulars. “The times” Dylan was thinking of evolved into something much bigger by the late 1960s. A variety of issues merged into a tumultuous period of change.

Sixty years later, the issues are different. They’re not all economic. The economic issues touch everyone in some way, though, so that’s what we will consider today.

Expectations Matter

The nice thing about economics is we sometimes see hard data highlighting important changes. We may not know the meaning, of course, but we can see something is off.

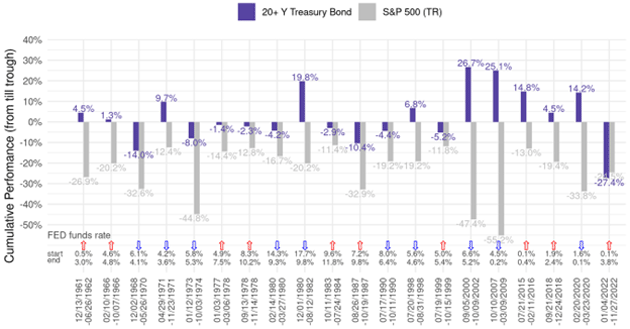

For instance, here’s a chart showing the S&P 500 Index’s worst historical drawdowns (the gray bars) since 1960 and Treasury bond returns for the same period.

Source: Michael Gayed

This nicely illustrates why investors so often diversify between stocks and bonds. Bonds rise whenever stocks hit a rough stretch. Worked like a charm every time… until now. So far this year bonds dropped even more than stocks.

That’s a problem for “balanced” portfolio strategies like 60/40. But more to our point, the breakdown of such a once-reliable relationship points to something bigger. What combined to so badly hurt both stock and bond prices at the same time this year?

The obvious answer is inflation and the surrounding policy changes, COVID and the response globally to it, plus war-related energy disruptions. The removal of excess monetary and fiscal stimulus hit asset prices that had risen more than they should have. We are seeing some improvement, making some expect a return to the pre-COVID “normal.” I’m not so sure.

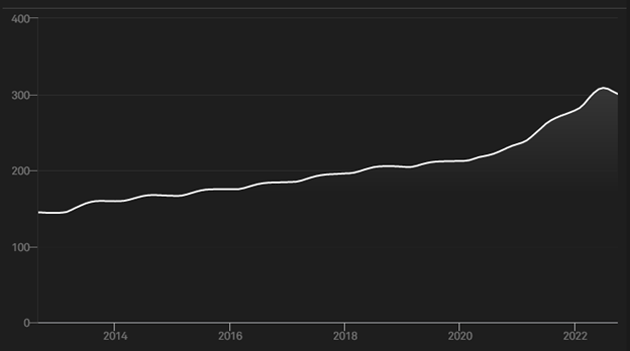

We see a different pattern in housing. Here’s the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller US National Home Price Index (which, by the way, should also win a prize for longest index name).

Source: S&P Global

All real estate is local, as they say, so your area may be different. This national benchmark shows home prices roughly doubling between 2013 and 2022, but recently starting to bend down. So here again, we see reduced inflation pressure, yet homes remain quite expensive.

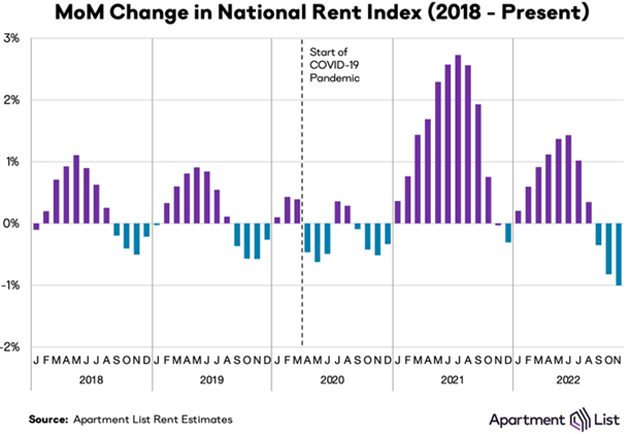

We also see a small reversal in apartment rent increases. Apartment List maintains a national rent index which shows declines the last three months.

Source: Apartment List

The inflation data tries to reflect that rent changes only when people move or renew their leases, which typically happens yearly. This softness will affect CPI and PCE only slowly, assuming it continues, which we don’t know (but the market kind of assumes). A recession that brings higher unemployment and lower wage growth would likely push rental rates lower, but supply is also lacking in many areas.

The common thread in energy, housing, and most other living costs: softening with limits. I don’t expect to see 2019 nominal prices again for almost anything. And note that word “expect.” Expectations matter because they drive behavior. If our collective psychology is now telling us to expect generally rising prices instead of the steadily falling prices since the 1990s (though with exceptions like rent and health care), we are in a different economic ball game.

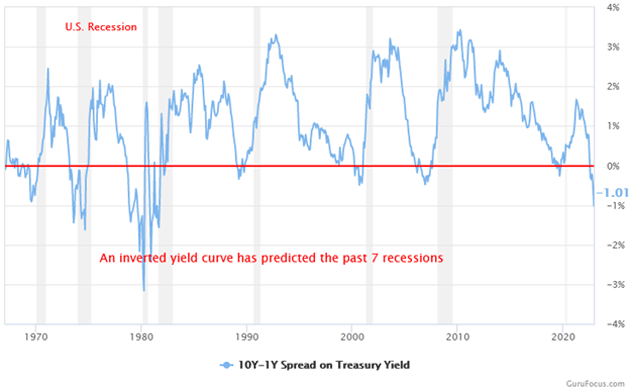

Now, that’s not to say prices will rise all the time. Recessions are deflationary and I think we will probably enter one soon. The yield curve agrees. The 10-year/1-year spread is inverted more widely than at any point since the 1980s.

Source: GuruFocus

It’s probably not a coincidence the last inversion of this magnitude also happened in a time of persistently high inflation. In that case, inflation did fall. It didn’t fall to anything like the 1%‒2% range we came to expect in the 2010s. Nor, I think, will it do so this time.

“More Frequent and More Violent”

I want to draw your attention to a very important thought piece in Foreign Affairs by my friend Mohamed El-Erian, whom you may have known as head of PIMCO. He is now president of Queen’s College at Cambridge University (congratulations by the way, Mohamed!). Mohamed isn’t one to exaggerate and he’s certainly no “permabear.” So when he says to expect “Not Just Another Recession,” as he titled the article, I pay attention. You should, too.

Below are some excerpts, with my emphasis added in bold.

“To say that the last few years have been economically turbulent would be a colossal understatement. Inflation has surged to its highest level in decades, and a combination of geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions, and rising interest rates now threatens to plunge the global economy into recession. Yet for the most part, economists and financial analysts have treated these developments as outgrowths of the normal business cycle. From the US Federal Reserve’s initial misjudgment that inflation would be “transitory” to the current consensus that a probable US recession will be “short and shallow,” there has been a strong tendency to see economic challenges as both temporary and quickly reversible.

“But rather than one more turn of the economic wheel, the world may be experiencing major structural and secular changes that will outlast the current business cycle. Three new trends in particular hint at such a transformation and are likely to play an important role in shaping economic outcomes over the next few years: the shift from insufficient demand to insufficient supply as a major multi-year drag on growth, the end of boundless liquidity from central banks, and the increasing fragility of financial markets.

“These shifts help explain many of the unusual economic developments of the last few years, and they are likely to drive even more uncertainty in the future as shocks grow more frequent and more violent. These changes will affect individuals, companies, and governments—economically, socially, and politically. And until analysts wake up to the probability that these trends will outlast the next business cycle, the economic hardship they cause is likely to significantly outweigh the opportunities they create.”

Mohamed knows how to drive home his main point. This isn’t just the normal business cycle. We are experiencing something entirely different.

He goes on to talk about the COVID-related supply disruptions, but he thinks more is happening.

“As time passed, however, it became clear that the supply constraints stemmed from more than just the pandemic. Certain segments of the population exited the labor force at unusually high rates, either by choice or necessity, making it harder for companies to find workers. This problem was compounded by disruptions in global labor flows as fewer foreign workers received visas or were willing to migrate. Faced with these and other constraints, companies began to prioritize making their operations more resilient, not just more efficient.

“Meanwhile, governments intensified their weaponization of trade, investment, and payment sanctions—a response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and worsening tensions between the United States and China. Such changes accelerated the post-pandemic rewiring of global supply chains to aim for more ‘friend shoring’ and ‘near shoring.’”

This resiliency corporations now seek is a good idea, but it’s not the way most have operated for a very long time. And that switch to resiliency will take time and money

Mohamed next describes the Federal Reserve’s mistake.

“But the longer central banks extended what was meant to be a time-limited intervention—buying bonds for cash and keeping interest rates artificially low—the more collateral damage they caused. Liquidity-charged financial markets decoupled from the real economy, which reaped only limited benefits from these policies. The rich, who own the vast majority of assets, became richer, and markets became conditioned to think of central banks as their best friends, always there to curtail market volatility. Eventually, markets started to react negatively to even hints of a reduction in central bank support, effectively holding central banks hostage and preventing them from ensuring the health of the economy as a whole.

“All this changed with the surge in inflation that began in the first half of 2021. Initially misdiagnosing the problem as transitory, the Fed made the mistake of enabling mainly energy and food price hikes to explode into a broad-based cost-of-living phenomenon. Despite mounting evidence that inflation would not go away on its own, the Fed continued to pump liquidity into the economy until March 2022, when it finally began raising interest rates—and only modestly at first.

“But by then inflation had surged above seven percent and the Fed had backed itself into a corner… Instead of facing their normal dilemma—how to reduce inflation without harming economic growth and employment—the Fed now faces a trilemma: how to reduce inflation, protect growth and jobs, and ensure financial stability. There is no easy way to do all three, especially with inflation so high.

No one should be confident the Fed can juggle those three balls without dropping at least one.

Finally, Mohamed zeroes in on something we don’t discuss enough. Businesses, like consumers, respond to incentives. And the incentives have changed.

“These major structural changes go a long way toward explaining why growth is slowing in most of the world, inflation remains high, financial markets are unstable, and a surging dollar and interest rates have caused headaches in so many countries. Unfortunately, these changes also mean that global economic and financial outcomes are becoming harder to predict with a high degree of confidence. Instead of planning for one likely outcome—a baseline—companies and governments now have to plan for many possible outcomes. And some of these outcomes are likely to have a cascading effect, so that one bad event has a high probability of being followed by another. In such a world, good decision-making is difficult and mistakes are easily made.”

More By This Author:

Pro Investor: "The Bear Market Ended In June"

An Interview With Keith Fitz-Gerald

Digital Shiny Objects

Disclaimer:The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more