Recession Scale

Economic news—and market reactions to it—increasingly resemble a tennis game. Spectators follow the ball back and forth, thinking something will happen but usually it doesn’t.

Last week, for instance, many investors got excited when they thought Jerome Powell was turning dovish. This was a misreading of a Powell speech. But it still produced a market rally, which further data then reversed.

That was partly wishful thinking. Federal Reserve policy has been the bull’s best friend for 20 years now, and maybe 40 years if we count since Volcker and the Greenspan Put. It’s easy for people who made a lot of money in these conditions to convince themselves that higher rates and QT are aberrations that will surely end soon.

Thinking Powell will lose his nerve isn’t crazy. He’s done it before, 2018 most recently. So did Bernanke and Yellen. Markets came to expect monetary conditions would always favor Wall Street. The fact that it distorted markets and prices of assets, commodities, and almost everything, while simply crushing savers and retirees, was seemingly unimportant to Wall Street types. They liked what it did to their portfolios.

That being said, I don’t think Powell will “blink” again. If stopping inflation means starting a recession, he will choose recession. Note, however, this “recession” may not look like past ones.

I suspect we are going to need a new vocabulary to describe the 2020s economy and beyond. It has been, and will remain, unlike anything we have ever known or seen. Slower growth (I think an average of 1% for the decade), relatively low unemployment (over the cycle), and volatility will be the themes. Lots of investment opportunities but not buy-and-hold broad market indexes. This will be a decade for active management.

The US is going to be less immune to global events, good or bad. A looming serious recession in Europe, for instance, will have an effect here, and not just on energy prices. China is already in a severe recession. What happens to demand for a wide variety of commodities and services, which are not cheap now, when China finally opens back up?

Today we will look at the landscape of inflation and GDP going into the end of the year.

Color Spectrum

Next month I’ll be writing my 2023 annual forecast letter. Preparing for that, I recently looked back at what I wrote in January 2022. Those annual lookbacks can be very humbling moments. At that point inflation had risen a lot but the Ukraine War and all its consequences were yet to come. Here’s what I said.

“At some point later this year we should resume what will be—and I hate to use this phrase because it is so trite—a post-COVID, post-snarled supply chain, new normal. We’ll face many of the same issues we had in 2019 plus a whole host of new ones. Some will be positive, some negative. For example, bringing back certain critical parts of the supply chain will be long-term positive for the economy, but also inflationary as it will increase prices. And it will take time…

“Further, the Federal Reserve is (finally!) moving to eliminate QE and theoretically will raise rates after that. I don’t want to get complicated here, but these two actions combined will further slow the velocity of money. Combined with the massive US debt, it is a recipe for economic slowdown…

“I think there is a reasonable probability that Jerome Powell will look at history and not want to be seen as Fed chairs Burns or Miller. He has an opportunity to drive a stake in the heart of inflation while risking only a mild recession. If he kills inflation, he can then provide stimulus which will bring the markets back. All will be right with the world, from Wall Street’s perspective.

“If Powell doesn’t kill inflation, he will go down as possibly the worst Fed chair in history, which is saying something. I think he’s made of sterner stuff. He doesn’t need the money being an ex-Fed chair. He is thankfully not an East Coast-trained economist. He is a businessman who recognizes the insidious nature of inflation.

“The markets are projecting three rate increases this year. Let’s call that over/under line. Nobody would be really surprised if they only do two rate hikes because the economy is soft. The major surprise would be if they do four rate hikes, pounding that stake into the heart of inflation.

“Note that many regional Fed presidents are also taking a harder inflation line, at least rhetorically, than they were a few months ago. Maybe they got religion in December.

“So, a forecast? I think there is a 70–80% chance of a real bear market and a better than even chance of what I hope will be only a mild recession.”

Again, that was me in January 2022. You can read the full letter here. We did indeed get that bear market. As for recession? Not officially but the first two quarters brought negative GDP growth. The full year will likely show 1% growth or less. Tighter monetary policy has lagging effects, so it’s not outlandish to expect even worse in 2023. The surprise will be if tighter Fed policy doesn’t produce a slowdown, even if the Fed pivots soon.

I don’t think that will happen. The FOMC won’t go straight from four consecutive 75-point rate hikes (in addition to two hikes of 25 and 50 basis points before those four) plus the anticipated 50-point hike next week to rate cuts in the first quarter or even the second. They will start by slowing the pace, then holding steady for at least a few months to see what happens. I’m confident the policy rate will remain where it is and maybe higher until mid-2023 at the soonest. Then when they do make cuts, we are not going back to the zero bound.

The more salient question is what effect this will have. Again, let’s remember the Fed wants to slow the economy and lower inflation. That’s the goal. They would prefer to do so as painlessly as possible, but they know it will hurt. The possibilities form a kind of color spectrum.

Soft Landing: Demand slows, inflation falls to 3% range, unemployment doesn’t budge, GDP growth stays mildly positive.

Mild Slowdown: Inflation still falls, but at a much slower pace. Unemployment rises above 4%, GDP holds near 0% or slightly below.

“Normal” Recession: Inflation remains high and forces the Fed to keep hiking to 5% or more. Unemployment and GDP growth would get significantly worse.

Severe Recession: Other events send inflation higher than we have seen thus far. The Fed clamps down hard, unemployment surges, and GDP sinks to -3% or more for the full year.

Hard Landing: This would be a 1970s rerun, with double-digit inflation making the Fed raise rates to 10% or more, generating widespread business closures and mass unemployment.

Other permutations are possible but, in all scenarios, the key variables are inflation and Fed policy. Inflation will drive Fed policy, but this is a one-way street. Fed policy doesn’t drive inflation, at least not without significant lag time—certainly multiple quarters if not a year or longer.

We will see where I come down for my forecast. Right now I think a “Normal” recession is the base case, but events (either good or bad) can always overwhelm it.

Housing Bust?

The Fed’s main power is its control of interest rates and liquidity. This power has limits, but it can seriously affect highly leveraged segments like housing. Let’s look at what is happening there because it’s not quite what you may think.

Between higher inflation expectations and the Fed’s exit from buying mortgage-backed securities, home mortgage rates are up significantly this year—enough to let a little air out of the housing bubble. Prices have dropped in many areas, making builders scale back their plans. But it’s not a “crash” yet.

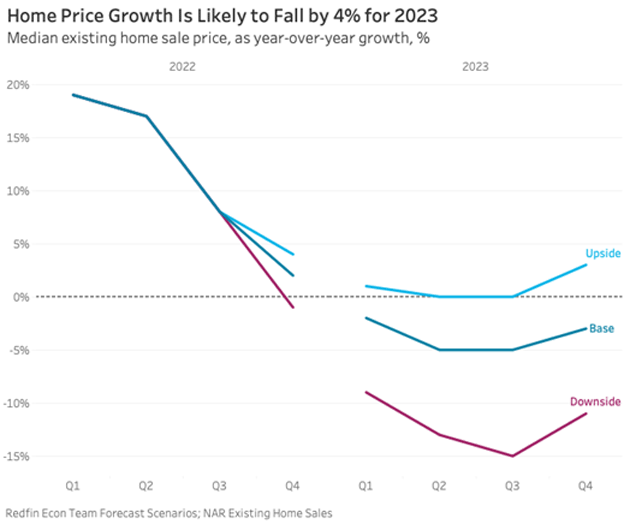

Redfin, for example, expects the median US home price to drop about 4% in 2023 to $368,000. If it happens, that will be the first annual drop since 2012.

Source: Redfin

Looking at the year-over-year change, as in the chart above, makes this seem like a major change. But does it matter? Redfin’s own data shows the median home price was $293,000 in February 2020, just before COVID. So even with this drop, the median home will still be 26% more expensive than it was four years ago. And 30-year fixed mortgage rates have roughly doubled in that same time.

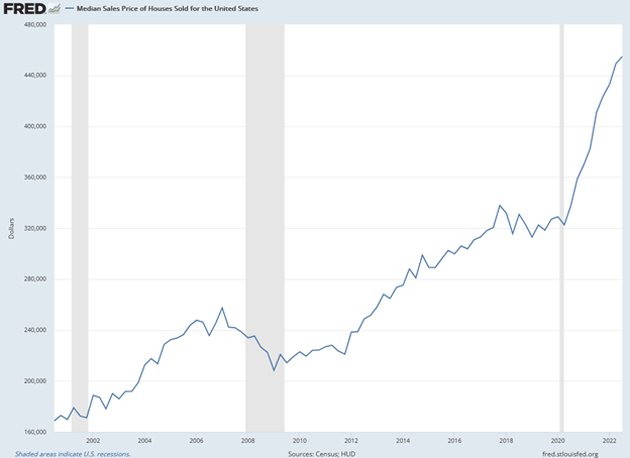

Here's a longer-term look. This is HUD data so the numbers are a little different, but the trend is similar.

Source: FRED

The median home price almost tripled in the last 22 years, far outpacing inflation. Yes, all real estate is local, etc. Some areas are more or less expensive. But nationally speaking, this won’t be some kind of buyer’s paradise unless prices drop a lot more and mortgage rates retreat quite a bit.

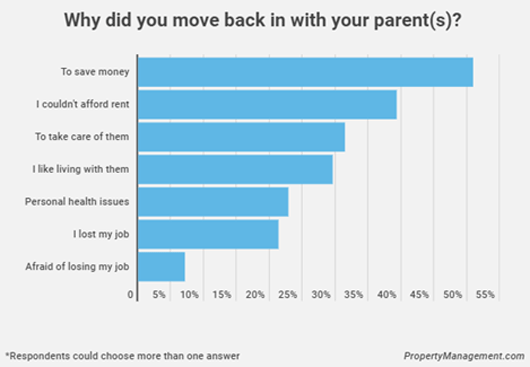

That will push more people into rental housing, mainly apartments. I noted last week how rental prices softened in recent months. But here again, perspective is important. Demand is outpacing supply in many places, keeping rental rates higher than many people can afford. And that explains the headline: Millions of millennials moved in with their parents this year:

“Soaring rents forced millions of young Americans to move back in with their parents this year, according to a new survey.

“About one in four millennials are living with their parents, according to the survey of 1,200 people by Pollfish for the website PropertyManagement.com. That's equivalent to about 18 million people between the ages of 26 and 41. More than half said they moved back in with family in the past year.

“Among the latter group, the surge in rental costs was the main reason given for the move. About 15 percent of millennial renters say that they're spending more than half their after-tax income on rent.

“The disruptions of the pandemic, which triggered massive job losses as well as a spike in housing costs, have driven an unprecedented shakeup in living arrangements. In September of 2020, a survey by Pew found that for the first time since the Great Depression, a majority of Americans aged between 18 and 29 were living with their parents.

Source: Crain’s Detroit

We all know rents and home prices are coming down in real time but that inflation numbers don’t reflect that. Let’s unpack that.

The inflation benchmarks incorporate changes in housing prices gradually to reflect the fact they don’t affect most renters until lease renewal time. Basically, the methodology of the way they measure means that they stretch the data over a year.

Let’s do a thought experiment. Year one a widget costs $1. Twelve months later it costs $1.10, thus widget inflation is 10%. Add another 10% to make the next year’s price $1.21. Widget inflation is still only 10% for the past year, although over two years it was 21%.

Now, suppliers wake up and offer more widgets and the price stays the same for the next year. The inflation rate will show 0% inflation even though the price is still up 21% from three years ago.

Inflation as we measure and report it is an annualized affair. Home prices are now modestly dropping. That will show up in the inflation figures 12 months from now. In fact, home prices stopped rising (depending on where you live) this summer, so owner’s equivalent rent is slowly rolling over.

Source: Durofy

My friend Barry Habib says it is like a roller coaster. As the cars go over the top of the track, there is a point where half the cars are falling and half the cars are still rising. That is roughly where we are on housing inflation. And like the roller coaster, the more cars roll over the top, the faster all the cars drop. But during that transition it still shows housing inflation as a lagging effect.

Barry, who has won three out of the last 4 Zillow awards for most accurate housing and mortgage rate forecaster, says home mortgages will be 5% this summer. There is a great looming demand as household formation is getting ready to rise and there are not enough homes and apartments at affordable prices, thus young people living with parents. As Felix Zulauf says, the sun will come up and market prices will reset.

Put all that together and we can see that even in a sector where it has a great deal of influence, the Fed’s efforts thus far are only modestly reducing prices. That suggests rates will have to go quite a bit higher to have the desired effect.

Labor Scarcity

Another way to reduce consumer demand is to reduce consumer income by raising unemployment. Higher interest rates can do that although, like housing, with considerable time lags. The November jobs data shows no such thing happening yet. Job growth seems to have slowed over the last year but is still firmly positive.

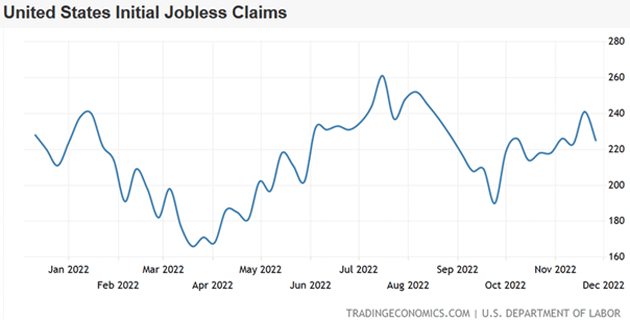

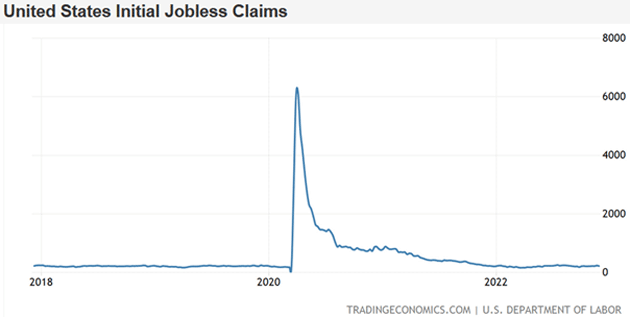

Yes, the number of layoff announcements does seem to be rising, particularly in the technology sector where many firms depend on the cheap liquidity the Fed is now withdrawing. But the actual numbers are still small. Our best gauge for this is weekly unemployment claims. Here it is over the last year.

Source: Trading Economics

Note the axis on the right side. We see swings in both directions but the numbers of new claims were quite low even in this year’s worst weeks. The five-year chart shows another perspective.

Source: Trading Economics

Following the big COVID spike, weekly claims are right back to the same flat line they were on in 2018‒2019. Consumer demand isn’t yet weakening enough to create the kind of layoffs seen ahead of past recessions.

This time, however, we have another factor: labor scarcity. Many employers lack the workers they need to serve existing demand. Others, where business may be slowing, are still reluctant to cut staff because the last few years demonstrated finding quality replacements can be tough. Not to mention training them. They calculate it may actually be cheaper in the long run to hold on to workers they don’t presently need.

Some believe the labor shortage will ease when the economy weakens enough, or government benefits diminish enough, to force more able-bodied people back into the labor force. This presumes there is a large pool of people who could be working but aren’t.

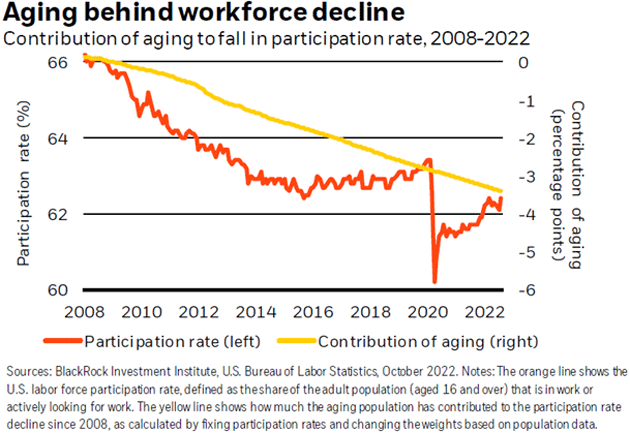

Labor force participation has indeed declined since 2020. The reasons have been subject to intense debate but are finally growing clearer. A recent BlackRock study pins most of the remaining shortfall on population aging.

Source: BlackRock

By their calculations, the drop in the participation rate is mostly explained by the number of people reaching retirement age, along with fewer who continue working past retirement age and more early retirements. It’s a demographic shift, which could shift back to some degree as recent retirees realize they need more income and return to work. Increasing job automation could help, too. But those probably won’t be enough to close the gap.

If the workforce keeps shrinking relative to population, odds favor either higher wages and more inflation, or reduced economic activity to match the labor supply. I don’t see economic activity falling because the older, retired part of the population will keep consuming while being (generally) less productive.

This means more inflation pressure in the years ahead. Add still-high energy and housing prices and it looks more and more like the Fed’s 2% inflation target will stay elusive—this time from above instead of below.

Such a scenario isn’t necessarily disastrous. People have been dealing with inflation for centuries. If we’re going into a period where inflation averages 3‒5%, it won’t be good but we will adapt. I actually think, barring the Fed getting a new religion and cutting rates too much, that deflationary pressures will come back to the fore in 3-4 years (maybe sooner).

Labor shortages could mean future recessions won’t produce the kind of unemployment we used to see. I’m really not sure what that will look like. The scales have to balance somehow. Maybe the business cycle will continue but at lower amplitude.

There’s one huge wild card in all this: China. The “Zero COVID” measures look increasingly unpopular, but COVID remains a serious threat there. Exactly how the regime will juggle these competing priorities is unclear. We know the Chinese Communist Party values social stability above all else. If that means sacrificing economic growth, I think Xi will do it.

Lower growth in China, much less outright contraction, could have a major impact on global energy and commodities demand. In theory, it could reduce prices enough to cut inflation pressure in the US and Europe. Or maybe not. We just don’t know. I mention it because it really could make a giant difference.

Next week brings the Fed’s last policy meeting of 2022. We’ll also get new “dot plots” that may reveal some of their thinking. The big mystery is how markets will react.

The Fed entered this year behind the curve and shouldn’t end it by proclaiming victory—which is how many will interpret a 50-point hike. Stopping inflation must remain top priority. The evidence I see doesn’t show any need to slow the pace, and I hope they don’t. We can talk about pausing in the second quarter. (Note: That’s pausing and not pivoting. Those who think the Fed will cut rates soon are engaged in wishful thinking.)

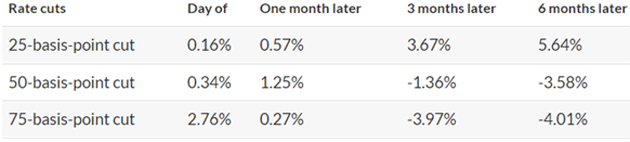

Like it or not, the Fed has become quite adept at forward guidance. We will know when they are thinking of cutting rates (slowly!) well in advance. But be careful what you wish for. Markets don’t always rise in the months after a rate cut and often fall. This table shows S&P 500 results for various time spans.

Source: MarketWatch

More By This Author:

A Decade Of Roller Coaster MarketsThe Economy Is A-Changin’

Pro Investor: "The Bear Market Ended In June"

Disclaimer:The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more