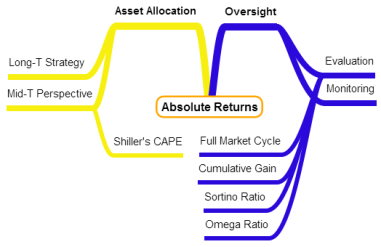

An Absolute Return Approach To Fund Evaluation

As investment advisors, traditionally we have taken an approach to investment oversight which assumes that 401k participant investors are rational investors. “Loss aversion” bias suggests otherwise. The following paragraphs will outline an approach which places the participant’s aversion to loss at the center of fund evaluations to help protect the plan sponsor from potential fiduciary breach claims.

Let’s first review this bias in the context of asset allocation decision-making.

The most well-known research on loss aversion bias today is reflected in DALBAR’s annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) study which they have been conducting for 20 years.

Here’s DALBAR’s own description of the study’s focus …

Each year, the QAIB report monitors the gap between leading indicators of investment performance and what mutual fund investors actually earn. The report has focused on the fact that in addition to availability and need for cash, the major cause of the shortfall has been withdrawing from investments at low points and buying at market highs.

Here’s their description of the most recent results …

The 2014 edition of QAIB shows a reversal of the improvement in investor decision-making, capping off the painfully slow improvement of the last three decades. The gap in 20 year returns of 10.65 percentage points in 1998 has narrowed to 4.20 in 2013. The current gap is the result of a 20 year return of 9.22% for the S&P 500 (SPX) compared to the average investor return of 5.02%.

In previous posts we have looked at using a mid-term perspective in the asset allocation approach to address loss aversion bias.

Here’s the latest piece Asset Allocation Quarterly – Stocks, Bonds, Cash and Strategy Expectations

For the purposes of investment oversight, there may also be an equal need to address participant investor concerns for principal loss by focusing on absolute returns when developing a first step quantitative screen for fund evaluation.

Using absolute returns to evaluate funds

Full Market Cycle – To focus on absolute gains and losses necessitates an approach in which investments are measured over a full cycle (one up and one down trend). Our most recent full market cycle for stocks (measured by the S&P 500) started in October 2007 and ran through approximately the end of November 2014.

To measure absolute return performance one might consider the following three measures: Cumulative Gain, the Sortino Ratio, and the Omega Ratio to develop an initial quantitative screen.

Cumulative Gain – This measure captures the growth of a hypothetical dollar investment over a period of time representing the total cumulative gain the investor realizes. To see the benefits of Cumulative Gain as an absolute return measure, please go to, Average Return vs Cumulative Gain – Which is a more robust performance measure?

Sortino Ratio – This measure of risk-adjusted returns analyzes an investment’s monthly returns by partitioning the gains and losses above and below a threshold return. Then the average positive return is divided by the investment’s negative return volatility or “downside risk” to calculate the ratio. To see the benefits of the Sortino Ratio as an absolute return measure, please go to, The Sortino Ratio

Omega Ratio – This risk-return measure analyzes gains versus losses to determine the probability of future gains and losses. Similar to the Sortino Ratio this measure separates gains from losses and then divides the cumulative sum of gains by the cumulative sum of losses. To see the benefits of the Omega Ratio as an absolute return measure, please go to, Investment Oversight Practice – The Omega Ratio

To compare a fund against its peers requires a database of monthly return data and percentile ranks per fund per measure.

From there an overall rank per fund per fund category can then be developed.

While the quantitative screen is just the first step in an overall fund evaluation process, it does serve to tie the participant to the oversight process by giving primary consideration to investment losses and “loss aversion” bias.

Is an absolute return approach a better first step screen for fund evaluations?

Maybe …

- Investors are not rational.

- It places participant behavior and therefore the participant at the center of the approach.

- It places the plan sponsor, investment advisor and the participant all on the same side of the investment oversight table by having a unified definition of risk.

Disclosure: None.

Great read, thanks.