Peak Passive And Market Efficiency

With more than $7 trillion tracking the S&P 500 alone, we estimate that index funds now encompass between a quarter and a third of the capitalization of the U.S. equity market. This extraordinary growth must surely rank as one of the most important developments in contemporary financial history.

When will it end? For at least the last five years, critics of indexing have argued that the growth of passive management is a “bubble” and, like all investment bubbles, destined to end with weeping and gnashing of teeth. We saw the Information Technology sector peak in 2000, and Financials in 2007. Might we now be approaching what some analysts characterize as “peak passive?”

What index funds today and technology stocks in the late 1990s have in common is that both have attracted large inflows. But that is where the similarity stops. The technology bubble was driven by active decisions, as investors allocated more and more weight to one segment of the market. The growth of indexing is driven by investors eschewing active decisions—in other words, by recognizing that most active managers underperform most of the time. As the technology bubble inflated, portfolios became more concentrated; as assets move from active management to index funds, portfolios become more diversified.

Despite these obvious benefits, we concede that indexing’s impact on market efficiency is ambiguous. It’s fair to describe the typical index portfolio as a price taker rather than a contributor to price discovery. This means that the valuation of index constituents is ultimately decided by active managers (and some factor indices) whose trades are motivated by their own research. And indexers do contribute to market efficiency indirectly, by taking assets from the least capable active managers, thus increasing the influence of their more astute competitors.

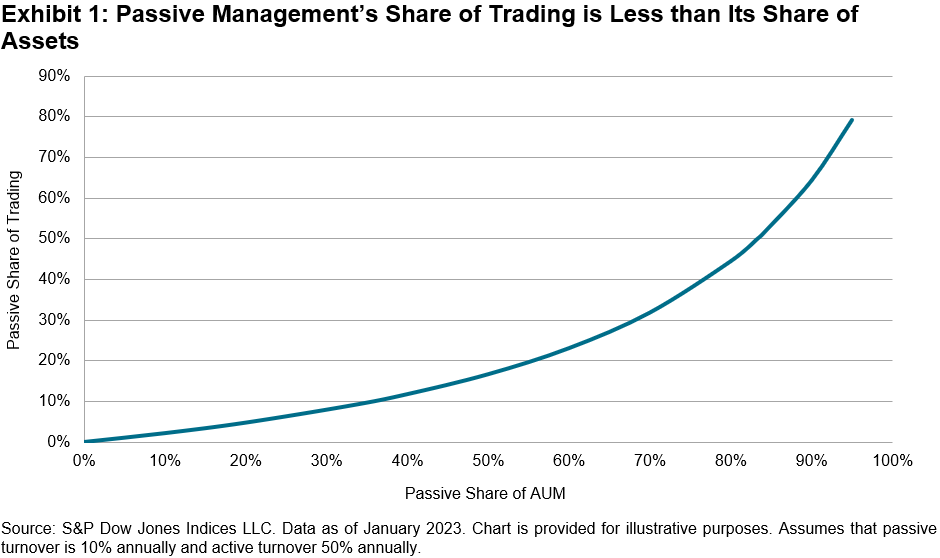

All this means that the idea of “peak passive,” while computationally unclear, isn’t conceptually wrong. But understanding where the peak might be requires us to distinguish between passive assets under management and passive trading.

Comprehensive cap-weighted index funds trade relatively little in comparison to active managers. Exhibit 1 shows that, on reasonable assumptions, if indexers own a third of the market’s assets, active managers will still do 91% of all trading. Under these assumptions, index AUM share must rise above 83% before active managers’ share of trading drops below 50%. And even at that level, there’s no a priori reason to assume that market efficiency would be impaired. (After all, active research is not unfailingly prescient.)

(Click on image to enlarge)

How will we know, at some future date, that markets are no longer sufficiently efficient? Presumably one of the indicia of market inefficiency would be a sufficiently large number of mispriced stocks, so that the value of successful active management would increase. This is a plausible outcome. But remember: the only source of outperformance for the outperformers is the underperformance of the underperformers. Active investment management remains a zero-sum game.

Even if we do approach peak passive, therefore, the active manager’s life will be no easier, and the benefits of indexing will be no less.

More By This Author:

The S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index: A Legacy of Dividend Increases In Technology

A Selective Approach To Style: The S&P Pure Growth And Value Indices

Good Things Come In Threes: Muni Bonds Appear Ripe For 2023

Disclaimer: See the full disclaimer for S&P Dow Jones Indices here.