The Road To A Post-Corona Boom (Healthcare) - Part 2

<< Read More: The Road To A Post-Corona Boom - Part 1

A major impediment to US growth is our complex and the expensive healthcare system. It adds tremendously to the process of hiring, it holds people in undesirable jobs and it creates enormous fear among those with pre-existing conditions. If we try to simply overwrite economic realities (like restrictions on pre-existing conditions) we end up with the government paying insurers massive correction costs without actually driving down the cost of providing care.

I could write up a dry article about my approach, but sometimes it is best to tell things through a story. This one is about the ballooning cost of healthcare and how I think we ought to be dealing with it.

---

I open the door to my new office and step in. A cardboard box is in my hand. It has everything I need. I look at the room, with its two walls of tinted glass, its clean carpet and its massive desk. It smells of industrial carpet cleaner, generously applied. It seems to perfectly match the scent of my dry-cleaned suit.

I close the door behind me, so nobody can see me. And then I smile the broadest smile of my life.

I am finally where I belong.

I step forward and gingerly place the cardboard box on the clear table. I remove the lid and stare down at the contents. Leaning against one side is my laptop and power cord. I remove it and place it on the desk in front of my office chair. I line it up perfectly with the desk and run the wire through to the power port. I take a moment to examine my handiwork and then I return to the box.

I look again. Then I pull out a single sheet of laminated paper. I place it, face up, exactly two inches from the corner of the desk. It will be on the near right corner for those who enter my office. It too is lined up with the desk. Then, on the paper, I place an empty pill bottle, a candy bar with a sale sticker on it and a napkin with a diagram jotted down. All are lined up with one another, perpendicular to my laptop so I can see them easily when I work.

Finally, at the bottom of the box is a collection of over 1000 letters. They come in all shapes and sizes and colors. I pick them out, one by one, and slowly and methodically tape them to my new office walls. I line them up in a pattern I laid out on my computer before coming here.

It has taken me all day, but I am finally done. I lift the box from the table and place it near the door. Then I turn around and look again at the space.

My laptop is in position, but more importantly so are the other objects: the paper, candy car, pill bottle, napkin and letters.

I smile again. This is where I belong.

Finally, I am being recognized.

It has been a long road getting here.

When I was in grade school, I wanted to fit in. But I never managed to do so. When troupes of girls would start obsessing over fashion or a band or even one another, I would try to get involved. I would read up on the subject and maybe watch a video or two. I would prepare a few comments so I could seem to be interested. Then, when I got a chance, I’d join in a conversation. I’d say my piece. But moments later, invariably, everybody would either laugh at me or drift away.

I’d go home and cry. And then I’d try again. I’d adjust my approach, of course. I’d analyze the probabilities of different elements combining to realize the desired outcome: popularity, or at least acceptability.

Time after time, I’d keep trying. Time after time, I’d keep failing.

It seemed I didn’t know how to communicate with my peers.

It took me a while to realize that the real problem was that they didn’t know how to communicate with me. I didn’t realize that they were really interested in the band or the fashion or how they did their hair. I thought they were just pretending. I thought it was all some sort of social dance necessary to achieve popularity. I thought it was a means to an end. I didn’t realize the dance itself was the point.

I thought, I truly believed, that they were like me. I thought they saw the world like numbers and patterns and geometric relationships. I thought they watched others walk and pulled out patterns in their movements. I thought they also saw equations in their movements through the playground; in the ways, they clumped and shifted. I thought they thought like I did.

But they didn’t.

It turned out I even dreamed differently than they did. Where they dreamed in images, I dreamed in formulas and integers and geometric relationships.

I had nothing in common with them. I was different from them. And so, over time, I pulled away from them. What I was interested in, they could not understand. And it seemed like the inverse was also true.

As I grew older, the differences only grew starker. As a child I consumed numbers. I read mathematics textbooks. I saw patterns around me. But, bit by bit, I began to create in numbers. Just as an artist would bring an image to life on a canvas, or a writer in words, I began to create in numbers. Patterns would speak to me, telling stories – capturing beauty only I seemed able to see and revealing truths others wanted to hide. I went through college this way. I got a degree in mathematics but the coursework was simple. Far more of my time was spent conjuring numerical realities that nobody but I seemed capable of appreciating.

I loved what I was doing. I loved the beauty of it. I loved the complexity. I loved the honesty. But I didn’t need to go college for any of it; I knew the math and I loved the numbers. But I didn't belong. I wasn't doing what I was meant for and I knew it. The one thing college gave me, that my art could not be a job. In my senior year, a professor of mine found me a position.

I was to be an analyst at the state government employee pension fund.

I expected I’d find my tribe there. I hoped to find my purpose.

But I didn’t. I didn’t know it at the time, but when I was hired, I was hired as a ‘diversity’ employee. I was considered disabled, autistic to be precise. I didn’t think I was disabled, but I did end up filling some sort of state quota. It was why I got the job. The fund was happy to hire me. People felt good having me around. But nobody really expected me to contribute much of anything. I was supposed to run routine reports and present them to management. I wasn’t meant to be tasked with anything too difficult. Of course, the jobs of my coworkers weren’t that much more advanced – although they may have disagreed.

It was all basic stuff done by basic people. Sure, the people were geekier than the average, but even they didn’t see the world the way I did. And I was far from fulfilled.

The job turned from okay to worse when my mangers started explaining pension accounting to me. It didn’t take me long to ‘get’ what they were explaining. But I could not accept it. It seemed like the accounting was just ‘corrections’ piled on top of corrections. Excessively optimistic projections were combined with theoretical future makeup of shortfalls which were themselves additionally enhanced. The rise in healthcare costs was forecasted to become something magically brought under control. And all of it was combined to make a system that was terribly broken seem less so. Even with all the lies, it didn’t work. What we published were projections of shortfalls that were themselves incredibly optimistic. I was hired to help them lie.

But I couldn’t accept making the numbers lie. To me numbers were beauty and their beauty was being rotted away. I tried to bury my head. I tried to pretend it wasn’t happening. But I couldn’t. I could see the lies, the corruption of the truth of numbers, spreading. I could see pensioners and then society being slowly overwhelmed by the truth the numbers told. I could see everything falling apart.

Hunger in the streets. Elderly homelessness. Lack of medicines. All numbers as promises that turned out to be lies.

And there was nothing I could do.

After I understood the problem, I spent every waking hour thinking about it. I wanted to solve it. But I kept coming back to two realities. Either the truth of the numbers was accepted (in which case people’s lives unraveled now as the promises made to them shrank massively under their very eyes). Or the lies were continued, promises were paid out and those paid last were left with nothing at all.

There seemed to be no other options.

Even the greatest manager could not stop it. All they could hope to do was slow it down.

It all seemed so hopeless. Then, I was diagnosed with cancer.

When I took a leave of absence, my co-workers pitied me; like I had suffered so much only to suffer this as well. I can’t say, at that point, that I disagreed. But what bothered me most of all wasn’t my own suffering or death; it was the gaping lie I was threatening to leave behind. It was the great unsolved equation that I could not understand or conquer.

The doctors tried chemotherapy and radiation and surgery. I watched as my odds of survival shifted and wandered. They jerked and spasmed at first. But then slowly they settled down. As I got sicker and sicker, my diagnosis got clearer. The numbers were not good. I was hopeless and it seemed like the best it could do was slow things down, a bit.

As cancer continued to rage through me, I began to it like I saw the accounting. Chemotherapy might slow cancer down – just like cutting benefits would – but the body would suffer terribly. The alternative would just encourage the runaway costs and when the end came it would be far more sudden.

Neither one was a winner.

And then I was entered into a trial for immunotherapy. The results were amazing. Within weeks, I was in complete remission. A few days after that, I was back at work. I was effectively cured. My own cells had been given the tools to rescue me.

I didn’t stop thinking of the fund’s problems as cancer. Perhaps, I imagined, some sort of immunotherapy would help. Instead of trying to force solutions from on high and trying to chase down individually replicating costs with roughly applied controls that damaged innovation and limited care, maybe something else could be done. Maybe individuals could somehow be used to drive down their own costs. Maybe, somehow, they could be empowered to create better outcomes; like white blood cells chasing down cancer.

But I didn’t know how to do it. I threw myself into the problem, but I had no practical ideas.

It was while I was having coffee at a café – alone – that I got my answer. A mother came and sat down near me. She had her son with her.

The boy gestured towards the convenience store next door and asked “Can I have a treat?”

The mother said, “Here are two dollars. Buy whatever you want, and keep the change.”

The boy ran off like a shot. I was curious about what would happen, so I stayed even after I finished my coffee. A few minutes later, the kid ran back – almost out of breath. In one hand, he held a candy car. It was marked with a prominent ‘Half Price’ sticker. In the other he held a receipt. He was proud, and he’d be taking home 75 cents in change.

The boy hadn’t had to pay for his treatment. But he’d been frugal and he’d done his tiny part in driving down the cost of candy.

A moment later, I realized that was the cure I was looking for. Instead of bombarding our members with cost controls, we could empower them. If they were brought in with a suspected lump, we would figure out the median cost of getting to the next diagnosis. And then, just like the mother did, we’d pay them a bit more than that. They’d shop around for diagnosis and keep the change. Then, they’d get to the next step. Perhaps it would be another diagnosis, with another traunch of money following to treat whatever they had. Advanced models and huge amounts of patient data would take the factors of their situation into account to determine what the mean was, and how much needed to be paid. Open, anonymous records, would enable a diagnosis to be checked by freelance auditors. Finally, we’d keep receipts of whatever they spent on their care – so we could update the median cost. But they, the patients, would keep the change.

But the fund was so large, and had so many patients that each of them, with each choice, would drive down the cost of care. The median cost of treatments would drop year after year, as providers competed for business. Our patients would be frugal and providers would cut costs in order to get their business.

Just as important, we would meet our promises to them. They’d get enough money to treat their diagnosis. We wouldn’t leave them uncared for.

There would be no lies in our numbers.

I grabbed a napkin from the holder and I began to chart the effects. I couldn’t do it perfectly, you can’t really predict innovation. But there are standard models. I could see costs plummeting while services improved – just like in high-tech or in laser eye surgery. New incentives would ripple through the system and rebuild it from the ground up. The fund might just survive.

I ran to the store and bought another of the candy bars. And then I ran back to work. I skipped my desk. I skipped my manager. I just burst into the office of the man who ran the entire thing. He looked up at me. And then I held up the candy bar and I explained my idea.

He was a numbers guy. He got it. And he made it happen.

Signatures had to be gathered, a vote had to be held. People needed to be convinced. But he made it happen. And soon, it was the way the fund managed its healthcare expenses. And it worked even better than I thought it would.

Indian providers – Indian! – got into the market for our patients. They offered high-quality surgeries at low prices and our patients responded. Local providers got more competitive. Clinics opened in the Bahamas. High tech got into the act. New therapies were designed – therapies designed to save money. Innovation, in delivery, in administration, in technology – exploded.

Costs, suddenly under pressure from a sort of social immunotherapy, plummeted. In the end, the fund was rescued. The lies were unwound.

The truth came back to the numbers.

A newspaper interviewed me about what I’d done. I told them the story. And then, the letters started coming in. They were letters of gratitude and of thanks. They were letters about worries lifted and fears erased. I read each of them. But I didn’t stop there. I calculated their count and colors and content and I put them up in ordered rows; bringing some bit of organization to their beautiful variety. I covered my cubicle in neatly arranged layers of letters.

And then, finally, I was promoted.

I was made a fund manager.

I wasn’t the top dog, I would never be a politician. But I was something close.

I was being recognized. I was being appreciated.

And in an odd little circle, I was finally being welcomed.

As I walked into my new office, my little cardboard box was with me. I unpacked it carefully, treating each item reverentially.

The pillbox used to contain a part of my immunotherapy. It told me the concept I must aspire to.

The candy bar was the one I bought on sale from the store. It told me how I could make the concept real.

The napkin was the one I wrote on in the café, it was the revelation of what I was possible.

Together, they are the reasons I am where I am.

I place all the items on the laminated paper. The paper is a print-out of rule changes the fund members voted for. They are what made the revelation real.

And the letters, the letters taped to the walls are the thanks I have received. They are the beauty of what I have discovered.

I look it all over then and I smile yet again.

I have a new job. Here, sitting at this desk, I will take the ideas of others I will figure out how to make them real. I will empower the members of our fund. I will be the beating heart of our organization.

I smile once more, truly happy.

My office is a tabernacle of financial immunotherapy.

Finally, I turn and pull open the door. It is time to get to work.

I have a purpose, finally, to fulfill.

--

A few notes on the story.

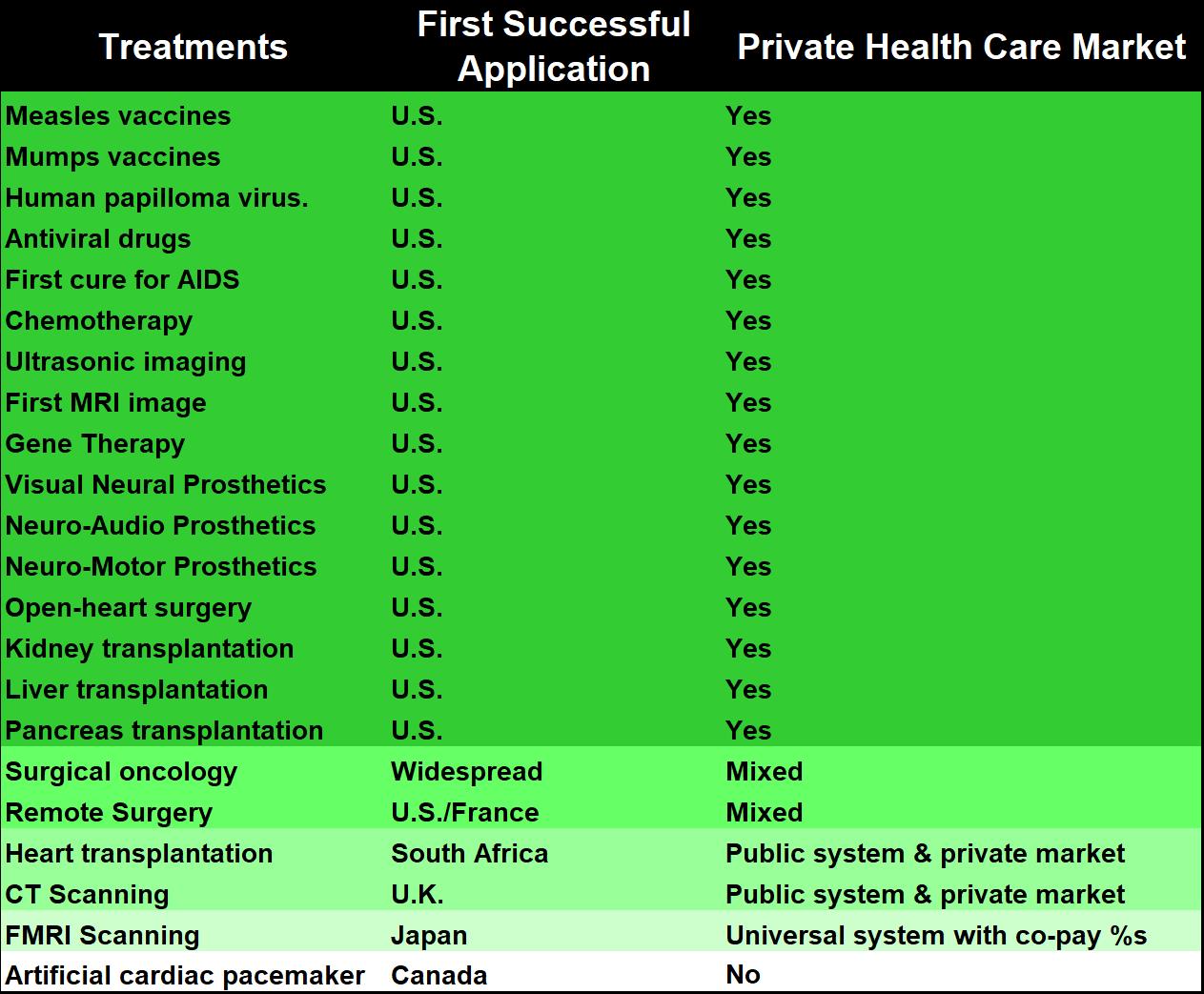

First, I see healthcare not as a right, but as an obligation. Society has an obligation to take care of the most vulnerable. Despite this high-minded ideal, the profit motive has been critical for the improvement of healthcare. There is hard evidence of this in the development of healthcare after World War II. Many countries socialized their healthcare systems. After that happened, 70% of major innovations were deployed first in the United States. As shown in the table, fully 90% have been rolled out in countries with private markets for healthcare. Only 2 of 22 innovations have been rolled out first in Europe (and one of those was rolled out in France and the US simultaneously). This paltry contribution is despite Europe being both wealthy and having a population equivalent to that of the United States. The United States has paid for the world’s healthcare innovation.

The great paradox of healthcare is that profit has made it an obligation.

We need to leverage the profit motive while delivering widespread care.

Second, I’ve seen the power of shopping around at work. The seeds of my approach come from Australia. There, the government pays a set amount for particular services. However, patients are free to pay more for better care: a private room, a particular doctor, or an anesthesiologist. The result is that people shop around based on price as well as quality. Australia does not have the money back provision. But the costs are incredible.

One of my relatives was in the ER in isolation for two days in Australia. As a non-national he was eligible for no government benefits. The total bill came to $1,300 US. A good hotel would have cost almost as much.

Shopping around can work in the US as well. An Australian relative was visiting the US. She had no insurance. She broke her rib and contracted pneumonia. A regular doctor was out of the question. We found a cash-only physician and paid $80 for an appointment. The physician recommended some basic imaging. We called around and found prices ranging from $120 to $500 (if we paid cash). We got the imaging done for $120 and returned to the doctor for a quick follow-up. The total bill, including medication, was $240.

She tapped into a market for illegal immigrants, where cost is a serious consideration. Shopping around drove price benefits.

The money-back idea will drive cost declines.

Third, my model has changed some I wrote the story. As I envision it now, the system would start with payment for the median cost of individual services not the treatment of conditions. A knee replacement would be X, an X-ray would be Y. The same money-back and auditing approaches would apply. A facility that overdid treatments in order to collect would be caught by incentivized auditors. Only over time, you would shift to costing based on condition, as in the story. The data structure needed to support that is huge and thus overly opaque.

Fourth, in the case of new innovations that raise the cost of healthcare I would have a board of experts to review the innovation. If it provides substantial benefits over existing treatments they would authorize it within the constraints of a QALY (Quality Adjusted Life Year) model. Once the product was in the market, patients would be free to not use it and get the difference in cash. If they chose not to, that would drive the median reimbursement down. Treatment would have to demonstrate its value not just to an insurance board, but to patients.

Finally, this story is about a single state pension fund. I chose it because it is more realistic than a change in the entire system. It would be a seed that could drive other changes. Given our current crisis, it might just be possible to reach for more.

Share your thoughts below…

Next segment: foreign wars.

I wrote a piece that brought together all the various policies under a single concept - empowering America... talkmarkets.com/.../empowering-america?post=265437

One more wrinkle: providers would be able to report monetary malingerers (those who seek out treatment to get the 5%) and would get a portion of their fraud as a reward. Likewise, patients would be able to report providers who stack on services to raise their cash input. Each of these would make it more difficult for fraud to be organized between patients and providers.

Third part added... foreign policy...

talkmarkets.com/.../the-road-to-a-post-corona-boom-foreign-policy-part-3

Your way of telling a story within an article is unusual for me, but interesting. Undecided if I like it as I'm more used to just reading facts. I didn't realize what was happening at first.

I will say that our health system, though expensive, is the also the best in the world as a result. But when it comes to COVID-19, tests and treatments should be free. Otherwise some who suspect they are infected, will do nothing, simply because they can't afford to.

We have an incentive system that rewards better health outcomes. We just need to adjust the structure so it also rewards better cost outcomes. It is like setting up a system of subsidized cars that only allows the very nicest cars on the road - paid for by third-party car providers with actual drivers having no incentive to shop around individually. They'll be nice cars, but they will cost a lot more than they should.

For those following Mr. Cox's Covid analysis and reports, there's some new news in. It looks like herd immunity isn't very likely:

edition.cnn.com/.../index.html

That is fascinating.

First, Sweden said it would *like* herd immunity but that wasn't the point. For them the point was balancing the cost (including in lives) of an economic shutdown against the life savings gained. This is an important consideration - the hidden deaths are substantial and have always been my concern. I don't think I've even claimed the virus wasn't dangerous - just that the total extended shutdowns would be more dangerous and not effective in the long-term.

Second, despite only voluntary and limited social distancing Stockholm has less than half the infection rate of New York. It *hasn't* spread like wildfire. We are still learning what works, but it seems like our social distancing can afford to be more targeted and still cut the infection rate.

Second, Stockholm has 3,900 deaths out of a population of just under a million. 7.3% infection implies 70,000 infected. This is a *very* high death rate comparatively (close to 5%).

6% of Miami-Dade had positive antibodies. There have been about 2,000 deaths and they have 2.7 million people - including many elderly. Back of the napkin deaths and they should have have twice cases with half the deaths of Sweden for 1/4 the death rate (1.2%).

Why does Florida have a lower death rate?

The fact is, we still don't know. New York has a 20% infection rate - despite a strong lockdown. Their death rates vs. antibody surveys are around 1.4% - a touch higher than Florida's.

London has a strict lockdown. 17% are infected. The death rate is 2.2%.

What I'm getting at is that the benefits of full shutdown vs. partial shutdown in places that can't really totally shut down (the border with Mexico is porous and 40 million Americans can't be without work indefinitely) are probably not that great - and the costs are huge.

Even in lives.

For countries that *can* shut their borders (Australia, New Zealand, Israel) a shutdown can actually suppress the virus. Otherwise you're looking at 'bending the curve.' Sweden hasn't had a hospital shortage, so bending the curve wouldn't help. They seem to have other problems in delivering care.

Who's right? The jury is still out. If there is actually a vaccine in the fall, Sweden will look pretty stupid. If not, as the costs continue to mount, Sweden might actually be well ahead of the game. Their 'limited social distancing' does seem to have limited the spread of the virus.

Of course, they have to get better at protecting their vulnerable (like Florida) and treating the sick. In these regards they are clearly well behind others. The high death rates implies a lot of infected old people relatively.

I am personally surprised their infection rate isn't higher. I was hoping it would be, as I'm sure many Swedes were. It would be great if they were nearing the end of their curve. If they had 1/4 the death rate they do Stockholm's infection rate would have been close to 30%.

Nonetheless this data continues to feed our understanding of what really works in countries that have already seen widespread community infections within their countries.

Sweden's infection control is working reasonably well - despite being limited. Their protection of the elderly/treatment of the sick, however, is quite poor.

There's still so much we don't know and so much conflicting info. I wonder how long it will be until we can look back with confidence and know the truth about all this.

It will be never. We still argue about 1918.

My current totally uninformed theory is that pre-existing bat coronaviruses have been giving humans in certain areas a level of immunity. This would be why Scandanavia is so different from the bulk of Europe.

I don't have any data to support this although I bounded it off an epidemiologist friend of mine (formally with the the US Army, CDC and WHO) and he is researching it.

Any updates from your epidemiologist friend?

I asked. Nothing yet.

Enjoyed, thanks.