What Caused The Great British Inflation?

You might think that you know what it means to say, “X caused Y”, but philosophers have been debating this issue for millennia. AI Overview lists several different approaches:

Different Philosophical Approaches

- Regularity Analysis: Focuses on patterns of constant conjunction between events, as seen in Hume’s work.

- Counterfactual Analysis: Examines what would have happened if the cause had not occurred; if the effect would not have happened, then a causal link exists.

- Manipulation Analysis: Views causation as something that can be manipulated or controlled, often with applications in the sciences.

- Probabilistic Analysis: Considers the likelihood or probability that a cause contributes to an effect.

I don’t plan to suggest that any one of these is always correct, but in my own field of monetary economics I’m interested in causality arguments with useful policy implications. When I say that a certain macroeconomic problem was largely caused by bad monetary policy, I mean that a feasible alternative monetary policy would have resulted in a much less severe problem. Because fiat money monetary regimes have almost unlimited control over nominal aggregates (at least in the absence of fiscal dominance), monetary policy is usually to blame for highly undesirable movements in nominal aggregates such as inflation and NGDP. (This claim does not apply to inflation created by supply shock problems.) And it is also to blame for undesirable real outcomes that are created by nominal shocks such as falling NGDP.

I’ll discuss a recent paper by Michael D. Bordo, Oliver Bush, and Ryland Thomas as a way of illustrating how reasonable people can differ on the question of causality, even when they have essentially the same view as to what is going on.

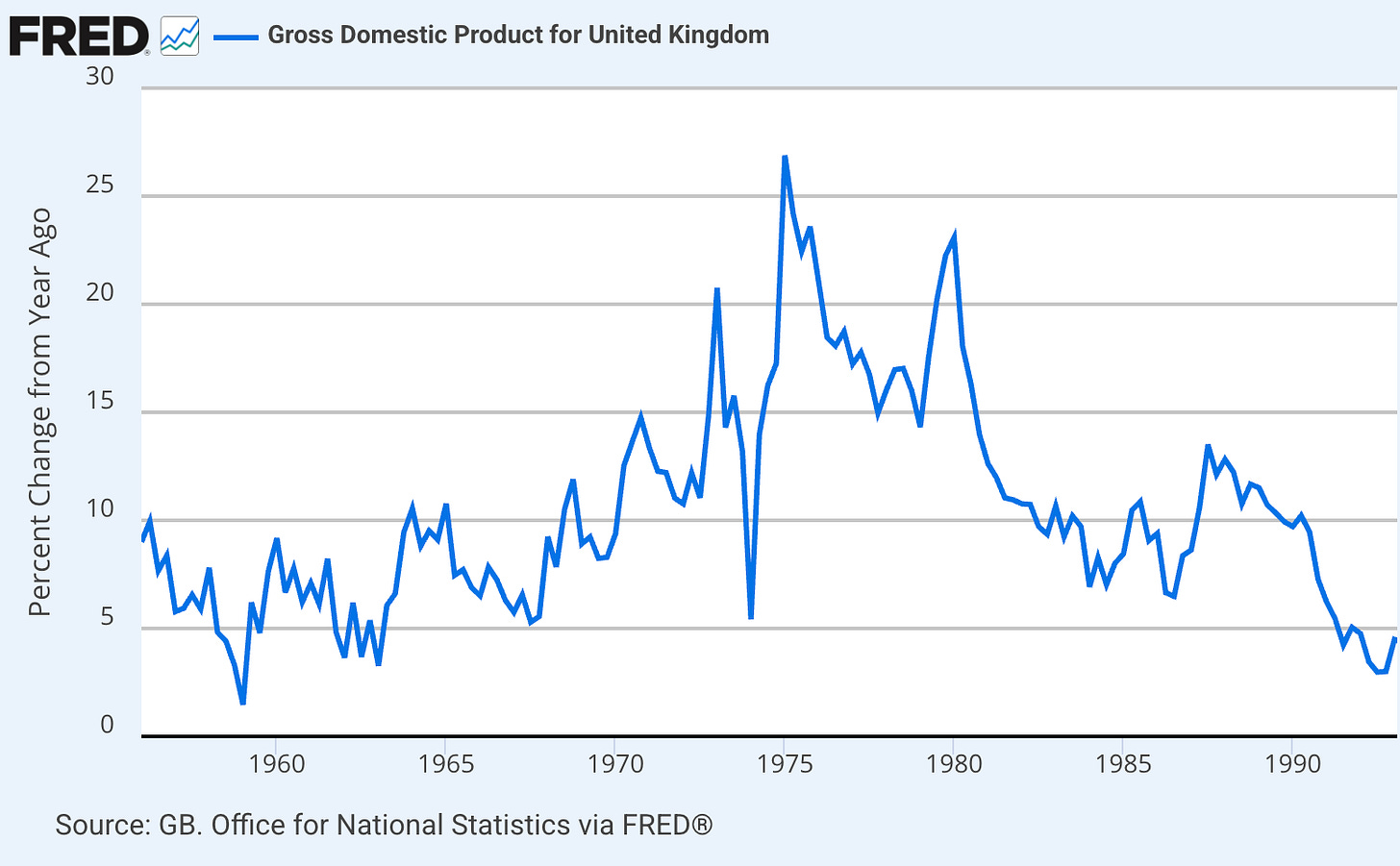

A graph of UK inflation during the 1960s through the 1980s looks similar to what we experienced in the US, with especially high inflation rates coinciding with energy price shocks. However, there was one important difference—Britain experienced considerably higher rates of inflation than the US, peaking at roughly 25% in the mid-1970s. Bordo, Bush and Thomas (BBT, p. 18) correctly argue that supply shocks alone cannot explain British inflation:

Even if there were adverse commodity and other supply shocks, it was not inevitable that there would be a large and persistent rise in inflation. Modern theory suggests that this would depend primarily on the policy response. Wage and other cost-push pressures in themselves could not be the ultimate cause of persistent inflation. They had to be accommodated by monetary and fiscal policy or, in the first instance, by the passive response of the banking system to a higher demand for credit to pay higher production costs in advance of revenue. Unless the authorities engineered a rise in nominal spending, high import price and wage inflation would simply lead to higher unemployment and ultimately a reversal of inflationary pressure.

The modern theory of optimal policy suggests that import price changes should be accommodated by policy if it is less costly to allow the required adjustment in real consumption wages to be achieved through higher goods prices (with the risk it de-anchors inflation expectations) rather than forcing down nominal wages through higher unemployment. Similarly, temporary cost-push shocks or transient real wage rigidity that drive a wedge between the current level of potential output and the efficient level of output might also allow some degree of accommodation of inflationary pressure (Blanchard and Gali (2009)). However, beyond that, any entrenched inflation is the consequence of the monetary policy rule, a misapprehension of the policy trade-offs involved or a failure to understand the inflation expectations process.

Elsewhere, I pointed out that the relative price of oil has hardly changed over the past 50 years, and thus almost none of the cumulative inflation during that period is due to oil. For every year where oil spikes pushed inflation higher (2021-22), there was another year when a falling relative price of oil pushed inflation lower (2023-24). And real oil prices are also about where they were pre-Covid, so oil explains almost none of the excess inflation since 2019. Trend inflation is essentially determined by monetary policy, not supply shocks.

I don’t think there’s much doubt that excess growth in nominal spending explains most of the inflation experienced by the UK during the period from 1967 to 1990. But there is debate about the relative importance of monetary and fiscal policy. On page 5 BBT discuss some of their key findings:

We also argue that changes in the fiscal policy regime were the key to bringing inflation back under control in the 1980s and early 1990s. The modern literature suggests that monetary policy was often not tightened sufficiently in response to inflationary shocks. However, nominal interest rates across the yield curve often exceeded 15% in the 1970s and 1980s in a belated attempt to control inflation and to try and ensure deficits could be financed by debt sales. That level of nominal interest rates proved to be a monetary policy threshold beyond which the authorities were not willing to go. Perhaps this was because they doubted the efficacy of further tightening or the willingness of agents in the economy to bear such a front-end loaded impact on incomes, even if real interest rates were low or negative. In each case, it was recognised that fiscal consolidation was the only path to securing low inflation as a complement to already tight monetary policy. We argue that inflation and, importantly, inflation expectations were only kept under control through a sequence of fiscal regime shifts. Each of these shifts involved a consolidation but also marked a progressive shift in fiscal regime that built on the foundations of the previous one. UK inflation was ultimately brought under control as much by changes in the fiscal policy regime as by the post-1979 changes in monetary policy regime and supply-side reforms emphasised in the current literature.

A purely modern perspective also abstracts from deeper historical, structural, and institutional forces that governed UK fiscal policy decisions, which it is also important to assess and understand. We discuss four underlying structural and institutional trends in the UK economy that worked to undermine fiscal sustainability in the UK in the early 1970s. These factors, some of which were unique to the UK, meant that any attempt to solve inflationary problems in the UK through monetary policy alone were doomed to be unsuccessful.

This is where we get into tricky issues of causality. Was any attempt to solve inflationary problems in the UK through monetary policy alone doomed to be unsuccessful because it this approach was technically infeasible, or because the UK government had a flawed model of monetary policy and wasn’t willing to use it appropriately?

A casual reading of these two paragraphs might lead readers to suppose that BBT were claiming that tight money failed to address inflation. A closer reading, however, suggests the actual problem was the UK government’s conflation of high interest rates and tight money. Note the reference to “even if real interest rates were low or negative.” Michael Bordo is a monetarist who is aware of the importance of this distinction.

Long time readers know that I judge the stance of monetary policy based on NGDP growth (or expected NGDP growth.) By that metric, UK monetary policy was highly expansionary during the 1970s:

(Click on image to enlarge)

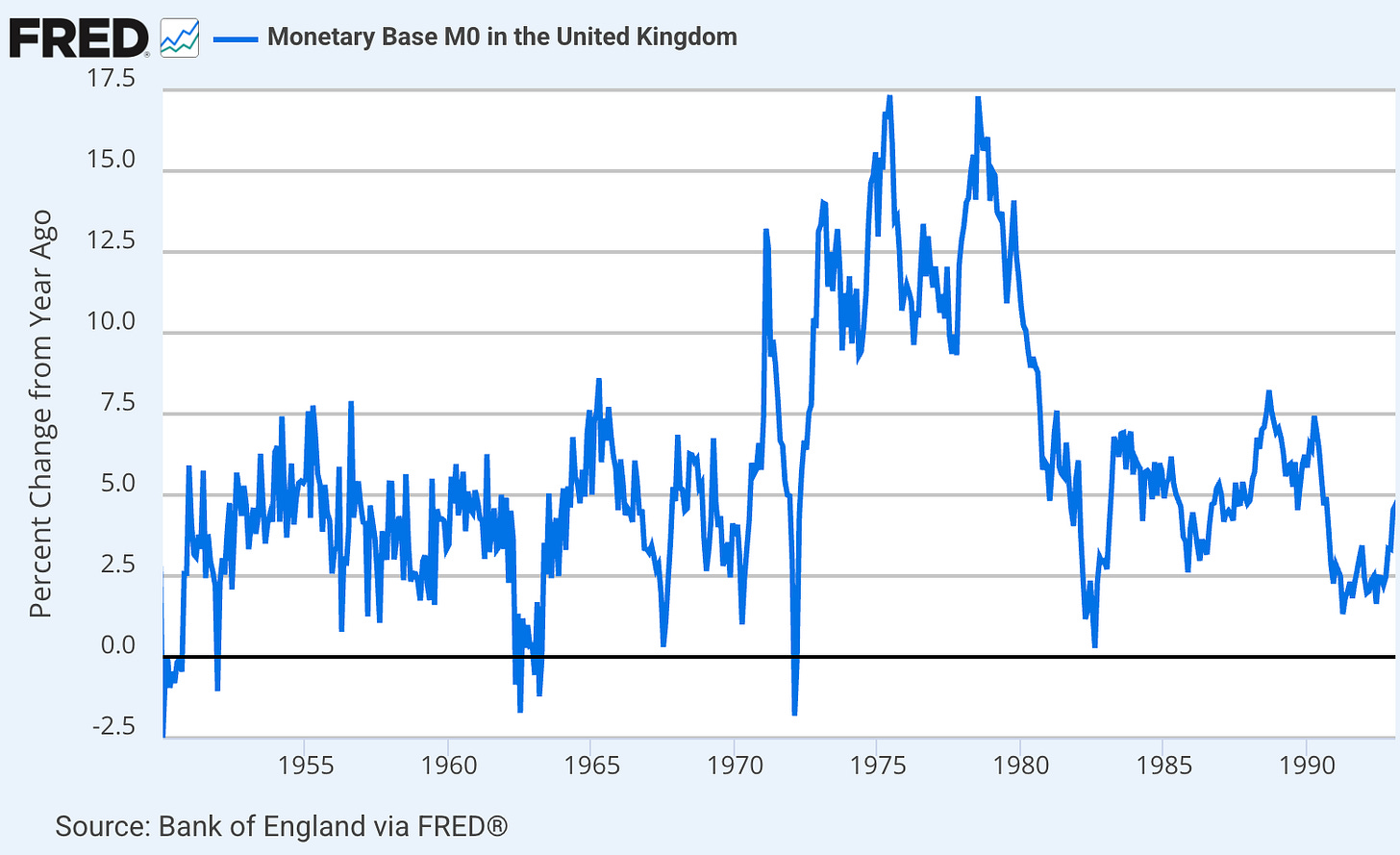

Critics complain that this is a tautology. They insist on evidence for some sort of “concrete step” taken by the central bank. Even the broad monetary aggregates have been challenged, as when Paul Krugman complained that the focus of Friedman and Schwartz on the declining M2 money supply during the early 1930s assumed away the liquidity trap—the problem of a falling money multiplier. Krugman pointed to the fact that the monetary base rose during 1930-33. My critics on the right have made similar arguments, pointing to QE (i.e., fast growth in the base) as evidence that money was not tight during 2009.

In this case, however, the British monetary base tells roughly the same story as NGDP; the Bank of England began printing money at a much faster rate during the 1970s. Here’s your concrete step, if you insist:

(Click on image to enlarge)

Another argument is that the BOE was not targeting the base, which was endogenous under a regime of interest rate targeting. But even if that were true, it is not really an objection to the claim that easy money created high inflation—rather it simply means that the BOE set its target interest rate at a level that led to rapid money supply growth. Recall that this was in the period before IOER, so base money was still “high powered”, and thus likely to create inflation if increased at too rapid a pace.

Before circling back and considering the role of fiscal policy, I’d like to consider an analogy using exchange rates as an explanation for Britain’s unusually high inflation rate. In the mid-1960s (under Bretton Woods), the UK pound was pegged at 2.80 US dollars. When I lived in London (in early 1986) it had fallen to was roughly $1.40, not too far from its current level. Thus, one could argue that much of Britain’s excess inflation (relative to US inflation) was caused by the British government’s decision to begin devaluing the pound in 1967. Unless I’m mistaken, that would be Robert Mundell’s explanation.

How do BBT evaluate the role of currency depreciation? Once again, their evidence is open to interpretation (p. 12):

From this proximate accounting viewpoint, the late 1960s pick up in price inflation seems largely attributable to wage costs. Despite the devaluation in 1967 sterling import prices only appear to contribute a little to the 8pp increase in inflation.

Two things can both be true. From an “accounting viewpoint”, currency depreciation may have had relatively little impact on prices. On the other hand, in a counterfactual world where the pound remained pegged at $2.80, British fiscal and monetary policy would have had to be much less expansionary, allowing for far less growth in nominal spending. In that case, whether the inflation was “caused” by currency depreciation or by the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies that led to currency depreciation is largely a matter of taste—how one prefers to define “causation”.

Mundell often favored fixed exchange rates, and thus was likely to view currency depreciation as a “cause” of inflation. I favor floating exchange rates, and thus don’t generally regard exchange rate depreciation as a useful explanation of inflation. However, I did argue that dollar depreciation explains most of the US inflation during 1933. That’s because FDR used dollar depreciation as a lever to force the Fed to do something that it ought to have done on its own—adopt a more expansionary monetary policy. In contrast, UK depreciation seems like a belated response to expansionary monetary and fiscal policies undertaken for other reasons.

Nonetheless, I find it quite plausible that had Britain kept the pound pegged at $2.80, the UK price level would now be at roughly half of its current level. Although purchasing power parity doesn’t always hold, it is very unlikely that a policy decision made in 1967 would have much impact on Britain’s real exchange rate in 2025. In other words, exogenous changes in the nominal exchange rate mostly affect prices in the very long run.

Now let’s return to the fiscal/monetary policy debate. My reading of BBT is that the UK government had only a rudimentary understanding of monetary economics during the 1960s and 1970s. More specifically, they lacked Milton’s Friedman’s understanding of the importance of the Fisher effect (high i-rates don’t mean tight money) and the way that expectations affect the Phillips Curve (don’t try to target the unemployment rate with demand side policies.) According to BBT (p. 22), Edward Nelson had a similar view:

Nelson argues that the main reason why monetary policy was too loose was that the authorities had a non-monetary view of inflation. A key belief among many Keynesian economists and policymakers after WW2 was that inflation was largely a “cost-push” phenomenon, a key element of which were pressures arising from wage costs. Wages were viewed as essentially exogenous and the outcome of centralised bargaining between trade unions and employers. They did not believe demand was particularly sensitive to short-term interest rates. Nor did they believe that inflation would respond to economic slack. Effectively up until the point of full employment the short-run Phillips curve was flat and could shift upwards via exogenous increases in wage and other cost pressures. This viewpoint had its roots in what is commonly known as the post-war consensus that emerged after the end of WW2.

Given the flaws in the worldview of British policymakers, things like wage shocks might be said to have a causal effect on inflation, as policymakers attempted to accommodate them with more demand stimulus. And fiscal austerity might be seen as a solution to high inflation, even if at a deeper level is was a policy that worked by enabling tighter money (in the sense of slower growth in the monetary base and NGDP.)

From this perspective, it is not so much a question of who is right and who is wrong, rather it is a question of which explanation is the most useful. I prefer monetary explanations of demand-side policy failures, because I believe the central bank can and should generate fairly stable NGDP growth, at roughly 4%/year. When I claim the Fed caused a particular macro problem, I generally mean that it set policy at a position likely to lead to excessive or insufficient NGDP growth.

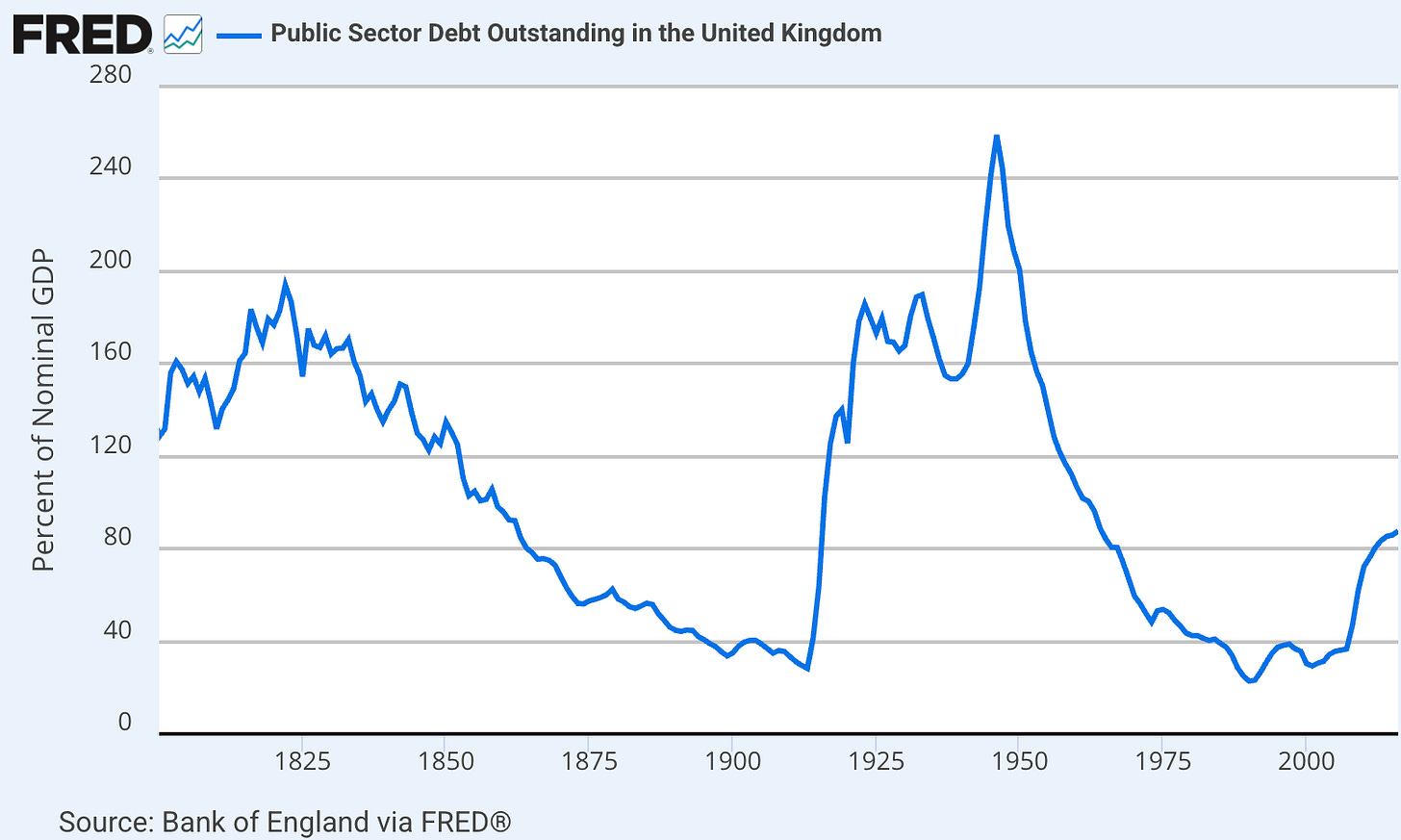

In a few countries, the fiscal situation is so dire that central banks are almost forced to accommodate fiscal stimulus. I don’t believe that applies to the US, nor do I believe it applied to the UK during most of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Here’s the UK net public debt as a share of GDP:

(Click on image to enlarge)

Notice that Britain’s public debt was far higher during the 1950s and 1960s, than during the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, fiscal dominance does not seem to provide an excuse for the highly inflationary policies adopted from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. In fairness, BBT provide evidence that there were unusually large primary deficits in the mid-1970s, so it is possible that fiscal policy played a role during certain limited periods.

Unfortunately, fiscal theories of the price level are difficult to test, as they generally depend on variables that are hard to estimate, such as the future expected path of fiscal policy. And I am reluctant to put much weight on an explanation that allows for 25% inflation when the public debt is 40% of GDP, and 3% inflation when the debt ratio is over 100% of GDP—and rising at an unsustainable pace. What evidence would refute the FTPL?

From my perspective, UK macro policy during the 1970s looks a lot like US policy in 2021-22; fiscal and monetary authorities making similar but independent mistakes, because of a similarly flawed worldview regarding their ability to use demand stimulus as a tool for creating jobs.

Overall, I highly recommend this paper to anyone interested in the history of British macroeconomic policy. It is full of important insights about the complex interrelationship between intellectual trends, policy changes, and macroeconomic outcomes. I hope that we’ve learned enough so that a given non-monetary “causal” factor that might have been relevant in the 1970s is much less of a factor today, but given what happened in 2021-22, we should not rest on our laurels.

My answer to answer the question in the post title is that the Bank of England caused the Great British Inflation.

More By This Author:

What Should The Fed Have Done In 2008?

Right For The Wrong Reasons

The Juggler