What Should The Fed Have Done In 2008?

David Beckworth recently directed me to an interesting twitter thread:

In this post, I will quibble with the claim that I would have favored a zero interest rate policy in late 2007. But first I’d like to say that I feel slightly churlish in making this point, for two reasons:

-

I’m flattered that a talented young economist like Zach Mazlish would even recall the arguments that I was making back in the period after the Great Recession.

-

Given my actual views, it would be reasonable for a person to assume that I did favor a zero-rate policy in late 2007. For instance, I’ve argued that Fed policy was too tight in late 2007, and even too tight in late 2008, when interest rates had fallen to zero.

[As an analogy, my actual view is that the Fed should stabilize NGDP per capita, or per working age adult. But I usually just refer to stable path of NGDP, under the assumption that population growth is fairly stable. So, I cannot complain if someone missed that distinction. If Trump succeeds in expelling millions of undocumented workers, then the distinction might become important.]

So how should we think about appropriate monetary policy counterfactuals? In my view, the wrong way is to focus on an entire alternative path for the interest rate. In fairness, Mazlish is not doing that—he’s merely suggesting an alternative move at one point in time. And that’s not an unreasonable request, given that the Fed’s operating procedure at the time was interest rate targeting.

In late 2007, there was no interest on bank reserves. Instead, the Fed set a fed funds target and used open market operations to hit that target. Given that policy regime, I believe the Fed should have cut rates by 1/2% in December 2007 (from 4.5% to 4.0%), rather than the 1/4% cut that was implemented. Better yet, I would have favored a 40-basis point cut, if the Fed were sensible and moved away from its clumsy regime of only moving in quarter point increments. I would have set the new target at 4.1%, as I believe a 50-basis point cut would have been a bit too large.

In fact, the quarter point cut led to a sharp fall in the asset markets, which pushed the economy into a mild recession in early 2008. Basis on data in futures markets, stocks almost certainly would have risen if the cut had been 50 basis points.

If you are surprised to learn that this is my actual policy view, don’t feel bad. My entire approach to monetary policy is highly unconventional, and those who focus on alternative paths for the policy rate are often going to have difficulty ascertaining the policy counterfactuals that I favor. Here’s how I prefer to approach the problem:

-

Start with the policy goals. Back in 2007, I would have preferred a 5% NGDP target, level targeting. That’s higher than what I prefer today, partly because population growth was considerably higher in the 1990s and 2000s.

-

Then I would try to estimate the appropriate interest rate path to maintain that sort of NGDP growth.

-

Most importantly, the appropriate path of interest rates would be far higher if the Fed successful maintained expectations of 5% long run NGDP growth, than if the Fed allowed NGDP and NGDP expectations to plunge far below the optimal path.

Obviously, the latter outcome is what actually happened in 2008. Both actual NGDP and NGDP expectations plunged far below the 5% trend line, and this dramatically reduced the neutral (equilibrium) interest rate. Paradoxically, large interest rate cuts in late 2008 were not enough to assure adequate NGDP growth, even though a credible policy of 5% NGDP level targeting might have required only very small rate cuts in 2008.

Wasn’t the housing slump also reducing the neutral rate? Yes, but only slightly. Note that short-term interest rates were in the 4.25% to 5.25% range in 2007, and the economy was doing fine despite a housing sector that was already slumping badly. And not only was NGDP growth in 2007 reasonably appropriate, NGDP expectations for 2008 were adequate as well. Monetary policy in 2007 was not significantly off course, which suggests that the neutral interest rate was still far above zero. Indeed, even in the first half of 2008, monetary policy was only slightly too tight. As late as mid-2008, conventional monetary stimulus could have prevented anything worse than a very mild recession.

Even though a housing slump can slightly reduce the neutral interest rate, it is NGDP growth that is the overwhelmingly dominant factor in determining movements in the neutral rate. I believe that a credible policy of 5% NGDP growth, level targeting, in 2008 and 2009 would not have required the Fed to cut interest rates all the way to zero, even in late 2008. But that’s because I also believe that a credible policy of 5% NGDP targeting, level targeting, would have greatly mitigated the severity of the banking crisis of late 2008. And that’s because I believe the late 2008 banking crisis was mostly caused by the impact of falling NGDP expectations on asset prices. (Australia avoided recession and its short-term rate never fell below 3% in 2008-09.)

And don’t underrate the importance of the “level targeting” qualifier. In my view, NGDP targeting alone would not have been enough to prevent the Great Recession if not accompanied by level targeting, that is, by a promise to return to the previous NGDP trend line if the economy went into a brief decline. It is the level targeting feature of the policy that generates confidence in future nominal spending growth. It is the level targeting feature that helps to stabilize what Keynes called “animal spirits”. It is the level targeting feature that would prevent the high-yield bond market from tanking. I suspect that a credible NGDP level targeting regime would have even prevented the Lehman failure.

If I am correct, if much of what we saw in 2008 was the side effect of Fed policies allowing NGDP expectations to crash, then it is quite possible that an alternative counterfactual of 5% NGDP targeting, level targeting, would have resulted in an interest rate path that remained hundreds of basis points above zero, all though 2008 and 2009.

To paraphrase George C. Scott in Dr. Strangelove, I’m not saying that we wouldn’t have gotten our hair mussed in 2008-09. In early 2008, soaring Chinese demand for commodities helped push the 12-month inflation rate up to a peak of 5.5% in July. (That’s the CPI, the rate of PCE inflation peaked at 4.1%.) Under my preferred alternative the inflation peak would have been even higher. And we all know what happened in 2021-22. But keep in mind that I was proposing stable NGDP growth, whereas in 2021-22 we dramatically overshot the NGDP trend line (which by that time was closer to 4%/year.) So even under my more dovish counterfactual the average inflation of the 2008-13 period would have been considerably lower than the average inflation rate of 2020-25. And there would have been no Great Recession.

To summarize, alternative interest rate paths are not a good way to think about monetary policy counterfactuals. It makes more sense to focus on alternative paths of NGDP growth, or better yet, alternative paths of NGDP growth expectations. The Fed cannot always insure stable NGDP growth, but they can and should stabilize NGDP expectations, at least to a reasonable extent. To me, that’s the only policy counterfactual that matters.

PS. A recent post by Stefan Gerlach compared monetary policy in two of the world’s most successful economies—Switzerland and Singapore. I especially like the Monetary Authority of Singapore, which uses the exchange rate as a policy instrument. It’s not that I believe exchange rates are the appropriate policy instrument (I favor using OMOs to target NGDP expectations), rather I appreciate any central bank that deviates from the dominant interest rate approach. Here’s how Gerlach describes the MAS policy:

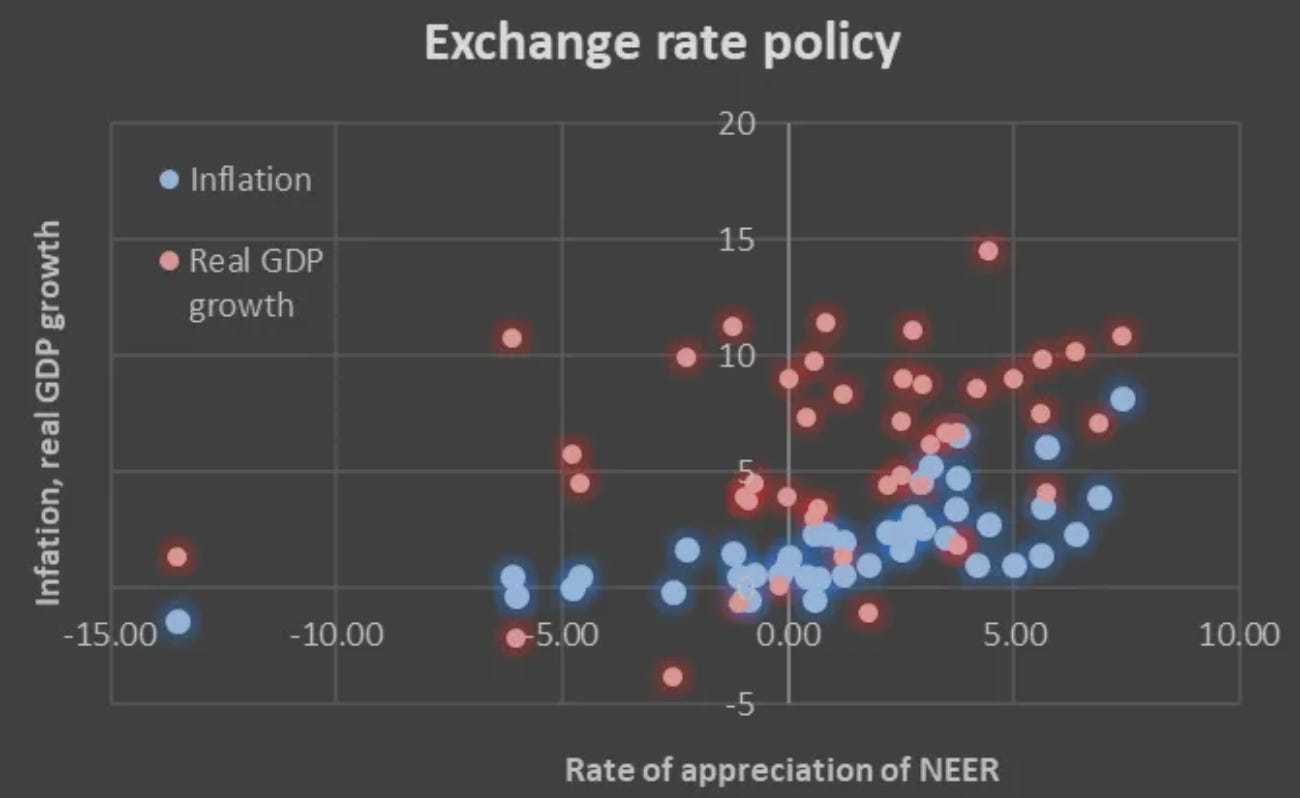

To see how policy is managed in practice, the chart below shows a scatterplot of the rate of NEER appreciation (horizontal axis) against inflation (in blue) and real GDP growth (in red) on the vertical axis, using annual data from 1981 to 2024. The correlation between NEER appreciation and inflation is strong at 0.68, while the correlation with real GDP growth is weaker at 0.36, but still meaningful. The implication is straightforward: when inflation picks up or growth strengthens, the MAS permits faster appreciation of the exchange rate to dampen demand.

And he provides a helpful graph:

Unless I’m mistaken, this is the exchange rate equivalent of a Taylor Rule approach. Note that we normally think of high inflation as a factor causing currency depreciation, for “purchasing power parity” reasons. The positive correlation between Singapore inflation and the value of the Singapore dollar presumably reflects the fact that exchange rates are being used to offset inappropriate moves in inflation. Sort of like the way you may push harder on the accelerator as you slow down going up a steep hill. Or the thermostat problem. In high inflation countries like Turkey, I’d expect a negative correlation between inflation and the value of the Turkish lira.

Of course, the same problem occurs with high interest rates, which can be used to reduce high inflation but can also reflect high inflation expectations. This suggests that it is not just interest rate counterfactuals that are difficult to model, exchange rate counterfactuals suffer from the same problem. Even the money supply is an ambiguous policy indicator.

PPS. Stephen Kirchner had a post that made me smile:

First-time FOMC voter Stephen Miran dissented in favour of a 50 basis points cut, in line with Trump's policy preferences, which might prove to be directionally correct, even if lacking in caution. The irony here, of course, is that Miran as a Federal Reserve Board member gets to do clean up on Miran as CEA Chair. More than any other member of the Trump administration, Miran has provided the fig leaf of intellectual respectability for the administration's tariff policies that are now weighing on the labour market. Waller and Bowman were presumably happy that the cut they sought at the last meeting was delivered this time, without seeking more.

If Waller were willing to sell his soul to become Fed chair, he would have voted for a 50-basis point cut. So, kudos to Waller.

PPPS. My qualified support for using the exchange rate as a policy instrument does not apply to countries where the exchange rate is not allowed to reach equilibrium, such as Argentina.

More By This Author:

Right For The Wrong ReasonsThe Juggler

A Serious Look At Interest Rates