Revisiting Exchange Market Pressure

Linda Goldberg and Signe Krogstrup have a revised version of a paper entitled “International Capital Flow Pressures and Global Factors”. They write:

we revisit these issues by recognizing that the observed responses of quantities of capital flows, exchange rates, and domestic monetary policy to global factors are interdependent and in many countries cannot be studied in isolation. In countries with fully flexible exchange

rate regimes, exchange rates move quickly in response to incipient changes in capital flows, supplementing or even obviating the adjustment observable in capital flow volumes (Chari, Stedman and Lundblad, 2021). In contrast, in fixed exchange rate regimes, managed floats, or even in some de jure flexible exchange rate regimes, central banks use policy interventions such as domestic interest rate changes and official foreign exchange interventions to reduce the realized exchange rate response to global factors (Ghosh, Ostry and Qureshi, 2018).1 In such cases, capital flow pressures may show up in foreign exchange interventions or in policy rate changes rather than in exchange rates. Accordingly, viewing capital flow responses to global factors separately from the exchange rate or policy response will provide an incomplete picture of the actual capital flow pressures at play.To account for the interdependencies between capital flows on the one hand, and exchange rate changes, foreign exchange interventions and policy rate changes on the other, we first present a new measure of international capital flow pressures, which is a revamped version of an Exchange Market Pressure (EMP) index. EMP indices are weighted and scaled sums of exchange rate depreciation, official foreign exchange intervention, and policy rate changes. Earlier versions of exchange market pressure indices have been used in a broad range of applications in the literature, from studying balance of payments crises (Eichengreen, Rose and Wyplosz 1994) to monetary policy spillovers (Aizenman, Chinn and Ito 2016b) and classifying exchange rate regimes (Frankel 2019). However, the weighting and scaling of the inputs have problematic features, leading those indices to mischaracterize the patterns of pressures across countries and over time, as discussed more extensively in the Appendix.

Our construction instead derives the relevant weighting and scaling terms within the index through an approach that utilizes key relationships in balance of payments equilibrium, international portfolio demands for foreign assets, and valuation changes on portfolio-related wealth.2 …”

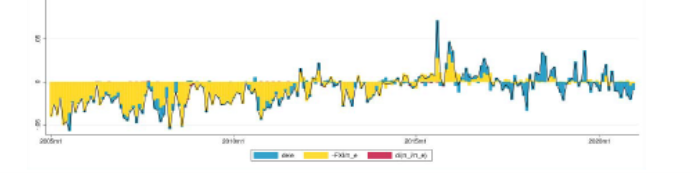

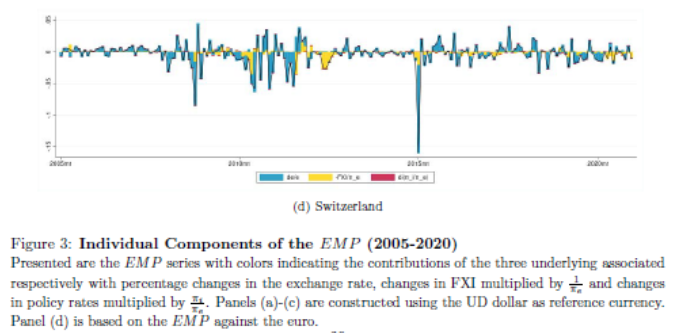

The paper describes in detail the (involved) calculation of their index. Figure 3 in the paper depicts the time series for four countries. I reproduce panel b and d (China and Switzerland, respectively) below.

Source: Goldberg, Krogstrup (2023).

One observation based on their indices:

During the highest stress episodes, countries on average allow more exchange rate variation to absorb capital flow pressures than during normal times and even during otherwise elevated risk sentiment. Some countries might recognize that intervention in the foreign exchange market may not be as effective during periods of extreme stress when currency pressures are large and might entail losing large quantities of official foreign currency reserves, so that they take at least a temporary currency depreciation.

“Foreign exchange intervention accounts for the majority of the EMP that is not attributed to exchange rate movements. The interest rate component accounts for almost all variation for very few countries. The contribution of the interest rate component is most pronounced in countries with high inflation and policy rates that have not been constrained by the effective lower bound and zero lower bound. Central banks in these countries have been able to use the policy rate more actively in response to capital flow pressures. …”

Some contrarian findings regarding safe haven currencies:

“…determinants associated with safe assets found little support in the data, with the size of the public debt and gross foreign positions occasionally and weakly showing significant associations. Financial market development and financial openness changes over time, with country fixed effects in specifications, do not differentiate risk behavior of realized excess returns.”

More By This Author:

The Employment Release And Business Cycle Indicators - Friday, Feb. 3The Cyclically Adjusted Budget Balance And Federal Debt Held By The Public: Time Series

Recession Probabilities Incorporating Foreign Term Spreads