Canada’s Job Market Will Have A Difficult Hill To Climb To Recover Lost Jobs

More than one year into the pandemic, and despite a speedy economic and jobs rebound in March, how long it will take for Canada’s labor market to fully recover is still very much unknown.

This is because the pandemic recession and the related job losses have not only been very unusual but also very uneven across different demographic and occupational groups. As well, Canada’s post-world war two experience with job recoveries seems to have little relevance in answering this puzzle.

After all, the pandemic triggered downturn in 2020 was entirely a supply shock due to Covid-19, and the supply shock spread across the entire world.

Further complicating any understanding of the full aftermath, Canada, the US, and indeed all advanced economies, are providing unprecedented massive injections of fiscal and monetary support to dampen the recession.

Once again, past business cycles in Canada provide us with only limited historical insights, since past recessions were repeatedly demand induced, and in addition, did not attract comparable hefty fiscal and monetary supports.

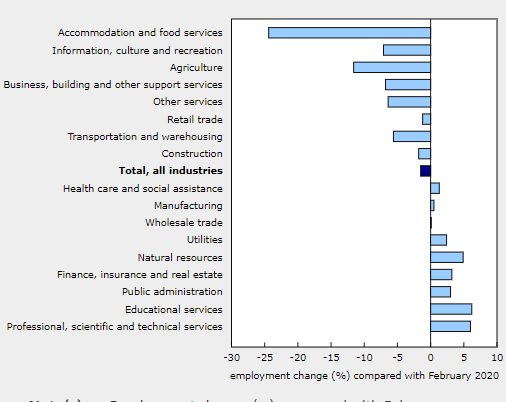

And then there is the different job market impacts from the pandemic downturn to consider. Thus, a professional trained in finance or technology would find today’s job outlook vastly better than last year’s and almost close to normal, notwithstanding the challenges of working from home for an extended period of time.

Further, Canadian employment in the public service, education and manufacturing already exceeds pre-crisis levels.

But if you are a young person embarking on a new career, and particularly someone who is looking for opportunities in higher education, hospitality or tourism, the job opportunities are quite grim.

And then there is the puzzling question - what does a healthy job market recovery actually look like? A simple starting point to keep in mind is that as of March 2021 there were 295,000 fewer Canadians employed than when the crisis started.

But the country’s population and its potential labour force has continued to grow even in a pandemic.

Moreover, due to Covid immigration into Canada almost ground to a halt in 2020 but is expected to exceed a 400,000 this year. Immigration is often unaccounted for in terms of the simple arithmetic often used in discussing the desire to return to former, pre-pandemic employment levels.

Moreover, we also know that many adults left the formal labour force last year, simply because there were no jobs. As well, even during the pandemic there are thousands of graduates from colleges and universities which should be entering the labour market and looking for employment.

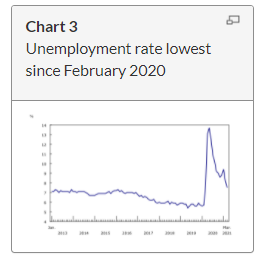

So, it is one thing to applaud the apparent rapid growth in jobs as restrictions unwind but this expansion will likely not quickly lead to real full employment. Canada’s unemployment rate fell to 7.5% in March, its lowest level since February 2020, though this measure has a number of well-known flaws.

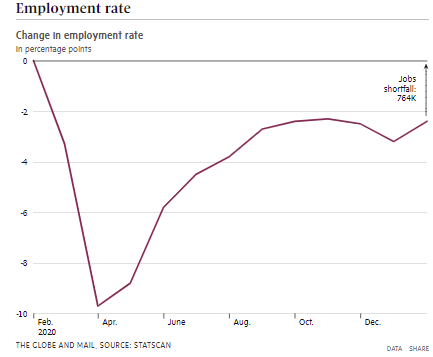

Although there is no perfect measure of the job market performance, one that stands out for this writer is the employment rate (i.e., the ratio of employment to working-age population).

During the early stages of the pandemic, the employment rate tumbled by nearly 10 percentage points, before clawing back most of its losses. Canada’s employment rate recently fell to 59.4%, still considerably lower than the 61.8% rate in February of 2020.

The closest Canada came to genuine full employment in recent years was early in 2020, just before the global pandemic hit. But as of March 2021, Canada’s economy was still 296,000 jobs below February 2020 level.

In closing, Canada’s job market has a steep hill to climb simply to restore February 2020 employment levels, and as stressed here, that pre-pandemic benchmark will be far from optimum in terms of presenting a genuine comfortable jobs picture.

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)