The Pandemic Recession And Central Banks

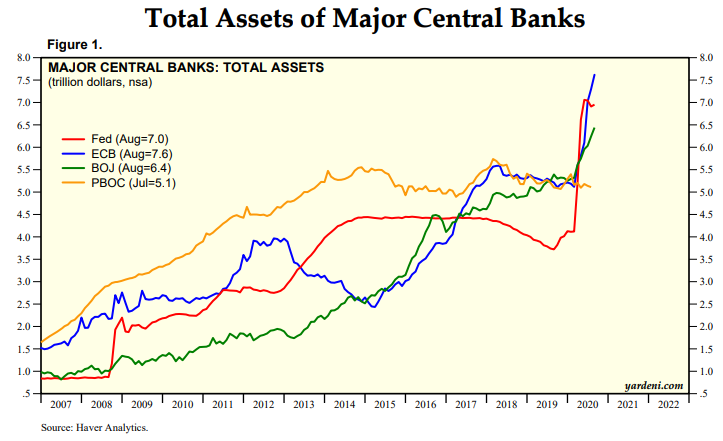

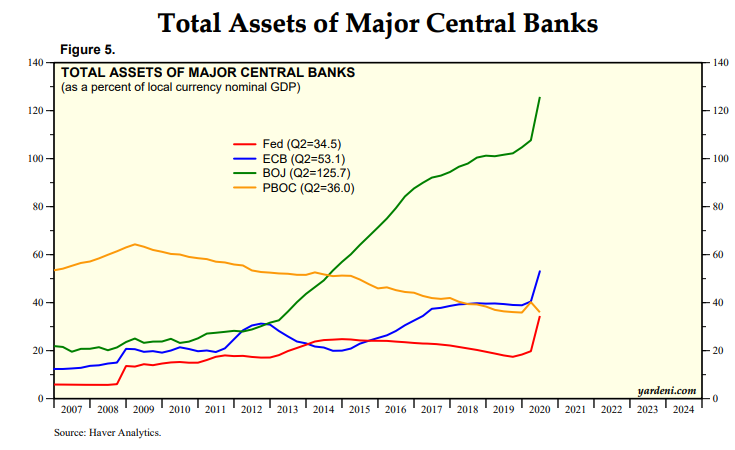

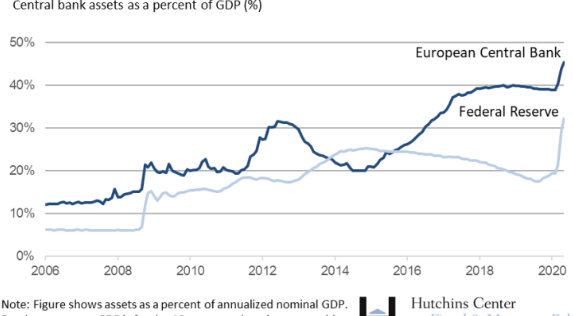

The pandemic recession has once again forced central banks to massively increase their balance sheets. Balance sheet growth, because of the severity of the pandemic recession, far exceeds the asset expansion triggered by the 2008/09 financial crisis.

“The vast array of measures taken by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank since March have been instrumental in reversing much of the dangerous tightening in financial conditions that occurred earlier this year. In its recent annual report, the Bank for International Settlements concluded — with apparent approval — that central banks have “deployed their full arsenal of tools, sometimes in unprecedented ways” and “have been able to cross a number of previous red lines to restore stability during this crisis”. The most obvious innovation has been to speed up and expand their government bond purchases, indirectly financing a large part of the increase in budget deficits needed to address the crisis. In only a few weeks, most of the major central banks have increased the size of their balance sheets by 7 to 16 per cent of gross domestic product, more than in the two years following the 2008 financial crisis.“ - ( Gavyn Davies, The Financial Times, July 12, 2020)

Before the international economic crash caused by the pandemic, it was widely assumed that central banks would not be able to mount a major new phase of asset expansion such as the one triggered by the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Back then there was an unparalleled expansion of central bank balance sheets in response to the Great Recession of 2008-09. Frankly, at the time most economists were surprised at the full extent of central bank asset expansion, though the policy was needed because economies were collapsing, and short-term interest rates had already declined close to zero.

In other words, in 2009 and 2010 central banks correctly concluded that they had no option but to support money supply growth and financial liquidity by aggressively adopting ‘quantitative easing’ asset purchases. Ultimately, however, and with a considerable time lag, quantitative easing seemed to work, even though inflation tended to decelerate everywhere and stayed dangerously low and, of course, short -term interest rates remained close to zero.

Thus, it is almost with a déjà vu sense that because of the pandemic recession quantitative easing has been adopted again, but in a much heavier manner than even back in 2008/09.

That is, with the pandemic recession still raging and with short-term interest rates once again close to zero, the large central banks vowed in March to go all out in terms of asset purchases in order to support the collapsing economies in North America, Europe and Asia.

As the following charts illustrate, since March the large central banks monetary expansion has been far larger, and more broadly based, than the one experienced in the previous decade.

While the current central bank asset expansion phase has not ended the pandemic recession, there can be no doubt that central banks have limited the damage and have once again supported the global financial system which would have otherwise crashed.

Of course, in practical terms central banks have also been monetizing enormous government deficits by purchasing government debt.

As worrisome as this is to the financial markets, this direction is still necessary to keep the liquidity of the international financial system functioning.

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

(Click on image to enlarge)

Interesting. The question is whether or not this unprecedented money supply expansion will lead to inflation.

Why do you think that's a possibility while the author does not?

I don't know. Thus far there has been inflation, but it's been confined to the financial market and other assets like real estate. It hasn't resulted in inflation yet (as the Fed reports inflation) because the new money hasn't entered the economy. The question is, what will happen when people actually want to spend their wealth on things other than stocks or real estate? There's also some issues with the way the Fed measures inflation. The price of food, for example, was 3.90% higher in September 2020 than in September 2019. It was actually much higher over most of this year once the money-printing started: tradingeconomics.com/united-states/food-inflation I don't know about you, but I'd call a rise in the price of food inflation! It's hard to deny that the cost of healthcare is still rising. I'd call that inflation too. The Fed's calculations tend to ignore things like this because that would mean that the government would have to pay out bigger cost-of-living increases to Social Security and other benefit recipients and that would strain the Federal budget more than it already is. So I don't think we'll see inflation as reflected in the Fed's numbers. I think we're already seeing it in the cost of goods that the average person buys!

thanks for your comment.

There is virtually no inflation risk on the horizon. Indeed, the risk is entirely one of low inflation, or in a worst case, deflation;

Regardless of who wins there election, there is no risk?

I had thought that the recession of 2008 was primarily instigated by the sale of derivative stocks, based on the lie that they would produce a high dividend rate, while instead they became worth far less than their purchase price. Perhaps that is an over-simplification, but certainly poor quality mortgages were bundled and sold as derivatives And certainly the value of those derivatives collapsed.

And just as certainly a whole banking system was very willing to sell that which they knew had very little value.

Amazingly enough, those "tightening of financial conditions" seem to have been caused by the actions of the banks that then needed to rescue everybody from them. And just as amazingly that enriched those very same banks.