The World’s Weird Self-Organizing Economy

Why is it so difficult to make accurate long-term economic forecasts for the world economy? There are many separate countries involved, each with a self-organizing economy made up of businesses, consumers, governments, and laws. These individual economies together create a single world economy, which again is self-organizing.

Self-organizing economies don’t work in a convenient linear pattern–in other words, in a way that makes it possible to make valid straight-line predictions from the past. Instead, they work in ways that don’t match up well with standard projection techniques.

How do we forecast what lies ahead? Today, some economists believe that the economy of the United States is in danger of overheating. Others believe that Italy and the United Kingdom are facing dire problems and that these problems could adversely affect the world economy. The world economy should be our highest concern because each country is dependent on a combination of imported and exported goods. The forecasting question becomes, “How will divergent economic results affect the world’s economy?”

I am not an economist; I am a retired actuary. I have spent years making forecasts within the insurance industry. These forecasts were financial in nature, so I have had hands-on experience with how various parts of the financial system work. I was one of the people who correctly forecast the Great Recession. I also wrote the frequently cited academic article, Oil Supply Limits and the Continuing Financial Crisis, which points out the connection between the Great Recession and oil limits.

Today’s indications seem to suggest that an even more major recession than the Great Recession may strike in the not too distant future. Why should this be the case? Am I imagining problems where none exist?

The next ten sections provide an introduction to how the world’s self-organizing economy seems to operate.

[1] The economy is one of many self-organized systems that grow. All are governed by the laws of physics. All use energy in their operation.

There are many other self-organizing systems that grow. One such system is the sun. Some forecasts indicate that it will keep expanding in size and brightness for about the next five billion years. Eventually, it is expected to collapse under its own weight.

Hurricanes are a type of self-organizing system that grows. Hurricanes grow over warm ocean waters. If they travel over land for a short time, they can sometimes shrink back a bit and grow again once they have an adequate source of heat-energy from warm water. Eventually, they collapse.

Plants and animals also represent self-organizing systems that grow. Some plants grow throughout their lifetimes; others stabilize in size after reaching maturity. Animals continue to require food (a form of energy) even after they stabilize at their mature size.

We can’t use the typical patterns of these other growing self-organized systems to conclude much about the future path of the world’s economic growth because individual patterns are quite different. However, we notice that cutting off the energy supply used by any of these systems (for example, moving a hurricane permanently over land or starving a human) will lead to the demise of that system.

We also know that lack of food is not the only reason why humans die. Based on this observation, it is a reasonable conclusion that having enough energy available is not a sufficient condition to guarantee that the world economy will continue to operate as in the past. For example, a blocked shipping channel, such as at the Strait of Hormuz, could pose a significant problem for the world economy. This would be analogous to a blocked artery in a human.

[2] The use of energy products is hidden deeply within the economy. As a result, many people overlook their significance. They are also difficult for researchers to measure.

It is easy to see that gasoline provides the energy supply needed for our cars and that electricity provides the power needed to clean our clothes. What is missing? The answer seems to be, “Everything that makes humans different from wild animals is something that was made possible by the use of supplemental energy in addition to the energy from food.”

All goods and services require the use of energy. While some of this energy use is easy to see, other portions are well hidden. Energy used in manufacturing and transport is most visible; energy used in services tends to be hidden.

Governments are major users of energy, both for their own programs and for directing energy use to others. Retirees get the benefit of goods and services made with energy products through pension checks issued by governments; researchers get the benefit of goods and services made with energy products through research grants they receive. Wars require energy.

Medical treatments are possible because of the availability of medicines and equipment made with energy products. Schools and books, as well as free time to study in schools (rather than working in the field), are possible because of energy consumption. Jobs of all kinds require the use of energy.

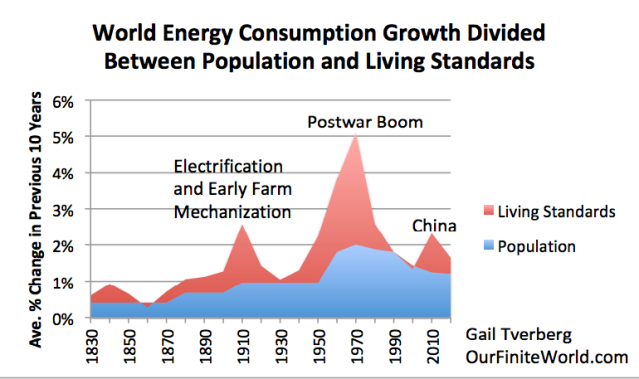

One thing we don’t often consider is that if energy supplies are growing sufficiently, they permit an expanding population. In fact, expanding population seems to be the single largest use of growth in energy consumption (Figure 1). Growing energy consumption also seems to be associated with prosperity.

Figure 1. World energy consumption growth for ten-year periods (ended at dates shown) divided between population growth (based on Angus Maddison estimates) and total energy consumption growth, based on the author’s review of BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2011 data and estimates from Energy Transitions: History, Requirements, and Prospects by Vaclav Smil.

[3] Prices of energy services need to be low relative to overall costs of the economy. Falling energy costs relative to overall GDP tend to encourage economic growth.

Most economists expect energy prices to represent a large share of GDP costs if energy is truly important. The statement above says the opposite. There are at least two reasons why low energy prices, and energy prices that are truly falling when inflation and productivity changes are considered, are helpful.

First, tools (broadly defined) used to leverage the labor of human workers often require considerable energy to manufacture and operate. Examples of such tools include computers, machines used in manufacturing, vehicles, and roads for these vehicles to drive on. The lower the cost to purchase and operate these tools, relative to the benefit of the tools, the more likely employers are to purchase them. If energy costs tend to fall over time, it becomes progressively easier to add more tools to leverage the labor of employees. Thus, employees become increasingly productive over time, raising the economy’s output of goods and services. For a similar reason, rising energy costs, if not offset by efficiency gains, present a barrier to economic growth.

Second, if the cost of energy production is low, it is easy to tax energy producers and thereby capture some of the benefit of their energy for the rest of the economy. If there is truly a “net energy” benefit to the economy, this is one way it gets transferred to the rest of the economy.

[4] There is indeed an energy problem, but it is not quite the same one that Peak Oilers have been concerned about.

The energy problem that Peak Oilers write about is the possibility that as easy-to-extract oil supplies deplete, oil production will reach a peak in production and begin to decline. Once decline sets in, they expect that oil prices will rise, partly because of the higher cost of production and partly because of scarcity. With these higher prices, they expect that producers will be able to extract at least a portion of the remaining oil resources. They also expect that higher prices will allow portions of the remaining natural gas and coal resources to be extracted. With higher prices, expanded use of renewable energy is expected to become feasible. All of these energy sources are expected to keep the economy operating at some level.

There are several problems with this story. First, it tends to encourage people to look for high oil prices as a sign of an oil shortage. This is not the correct indication to look for. Prior to 1970, oil prices averaged less than $20 per barrel. Comparing pre-1970 prices to today’s oil prices, current prices are already very high, at $75 per barrel. The idea that oil prices can keep rising indefinitely assumes that there is no affordability limit. Furthermore, a loss of energy consumption can be expected to reduce demand (because of its impact on jobs, productivity, and wages) at the same time that it reduces supply. If both supply and demand are affected, we don’t know which way prices will move.

Second, my analysis suggests that part of the story is that total energy consumption is very important, including oil, coal, natural gas, nuclear, and various forms of electricity. All of the attention given to oil has drawn attention away from the economy’s need for a range of energy types to keep devices of all types operating. Deciding to reduce coal usage because of pollution issues, or deciding to shut down nuclear because it is aging, has an equally adverse impact on the economy as reducing oil supply unless the shortfall can be made up with other energy products of precisely the type needed by current devices.

Third, my analysis suggests that energy consumption per capita needs to rise for the economy to function in the way that we expect it to function. If world energy consumption per capita is too flat, we can expect to see many of the symptoms that the world has been experiencing recently: more radical leaders, less cooperation among leaders, slowing economic growth and increasing debt problems. In fact, wars are possible, as are collapses of governments (as with the Soviet Union central government in 1991). The current situation seems to be more parallel to the 1920 to 1940 flat period than it does to the 1980 to 2000 flat period.

Finally, with low energy prices rather than high quite possibly being much of the problem, there is a significant chance that oil and other production will decline because producers do not make enough profit for reinvestment and because oil exporting countries cannot collect enough taxes to fund the many subsidies that citizens expect. This makes for a steeper energy decline than forecast by Peak Oilers; it also reduces the possibility that high-priced renewables will be helpful.

[5] Part of the world’s energy problem is a distribution problem; the world becomes divided into haves and have-nots in many ways. It is this distribution problem that tends to push the world economy toward collapse.

There are many parts to this distribution problem. One is the distribution of goods and services (created using energy) by country. Over time, this tends to change, especially as commodity prices change. Oil exporters are favored when oil prices are high; oil importers are favored when oil prices are low. The relative values of currencies can change quickly, as commodity prices change.

Another part of this distribution problem is growing wage and wealth disparity, as more technology is added. If there is too much wage disparity, low-paid workers often cannot afford adequate food, homes, and transportation for their families. Their lack of demand for goods made with energy products (because of their low wages) tends to work through the system as low commodity prices. This happens because (a) there are so many of these workers and (b) these workers tend to purchase a disproportionate share of goods and services that are highly energy-dependent.

[6] Debt-like promises play a major role in making the economy operate.

Taking out a loan allows an individual or business to purchase goods without saving for the purchase in advance. To some extent, taking out a loan moves up moves up the timing of purchases. At times, it even permits purchases that otherwise would not be possible. For example, if a young person tries to decide between (a) working at a low wage until he has saved up enough to afford to go to college and (b) taking out a loan and going to school now, so his wages would be higher in future years, his optimal choice will often be scenario (b). The time would likely never come when the low-paid individual could save up enough wages to afford to go to college. If the young person strongly desires high wages, his optimal strategy would be to take the loan and hope that his future wages will be high enough to repay it.

If the goal of the economy is to produce an ever-increasing amount of goods and services, growing debt can very much help this growth. This happens because, with more debt, more individuals and businesses can afford* to buy the goods and services that they want now. In a sense, debt acts like a promise of the future energy needed to make future goods and services with which the loan can be repaid. Thus, adding debt acts a somewhat like adding energy to the economy.

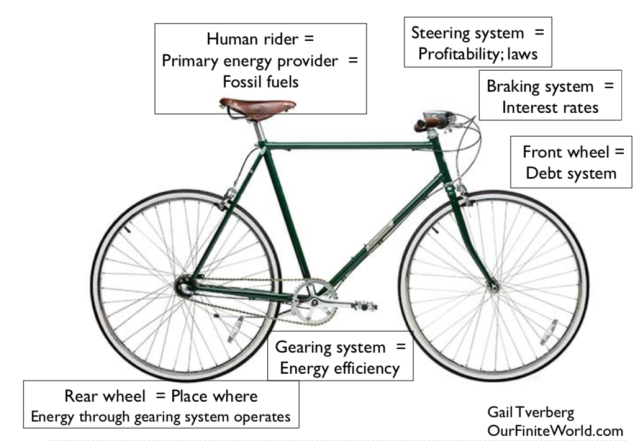

Because of the way debt works, the economy behaves much like a bicycle, with growing debt pulling the system forward. If the economy is growing too slowly, the tendency is to add more debt. This solution works if a rapidly growing supply of cheap-to-produce energy is available; the additional debt can be used to create a growing supply of affordable goods and services. If energy costs are high, the goods and services produced tend to be unaffordable.

Figure 2. The author’s view of the analogy of a speeding upright bicycle and a speeding economy.

A bicycle needs to operate at a fast enough speed (about 7.5 feet per second), or it will fall over. Similarly, the world economy needs to grow fast enough, or it will not be able to meet its obligations, including repayment of debt with interest. If the economy grows too slowly, debt defaults are likely to grow, pulling the economy down.

[7] It looks like it should be possible to work around energy problems with improved technology, but experience suggests that this approach represents only a temporary “fix.”

There are two issues that make improved technology less of a solution than it appears to be. The first is diminishing returns. For example, if a business faces a choice between (a) paying a worker to perform a process and (b) adding a machine to that can perform the same process, the business will tend to make the changes that seem to provide the largest cost savings first. At some point, as more technology is added, capital costs can be expected to become excessive relative to the human labor that might be saved. The issue of the diminishing returns to added complexity (which includes growing technology) was pointed out by Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies.

The second reason why added technology tends to be only a temporary solution is because it tends to lead to wage disparity. Wage disparity has a tendency to grow because of the greater specialization and larger organizations needed to coordinate the ever-larger projects. The reduced purchasing power of those at the bottom of the hierarchy can eventually bring an economy down because it can lead to commodity prices that are below the level needed to maintain the extraction of fossil fuels. Fossil fuels are required to maintain today’s economy.

[8] Renewable energy has been vastly oversold as a solution. What is needed is an ever-increasing quantity of inexpensive energy in forms that match the energy needs of current devices.

The wind and solar story is far different from the story presented in the press. Essentially, wind and solar are extensions of today’s fossil fuel system. The evidence that they are truly beneficial to the economy is shaky at best. We know that if energy sources are truly transferring significant “net energy” to the system, they generally can afford to pay high taxes. The fact that wind and solar require subsidies raises questions regarding whether standard calculations are providing accurate guidance. The press rarely mentions the high tax revenue that high oil prices make possible, worldwide. Tax revenues largely support many oil exporting countries.

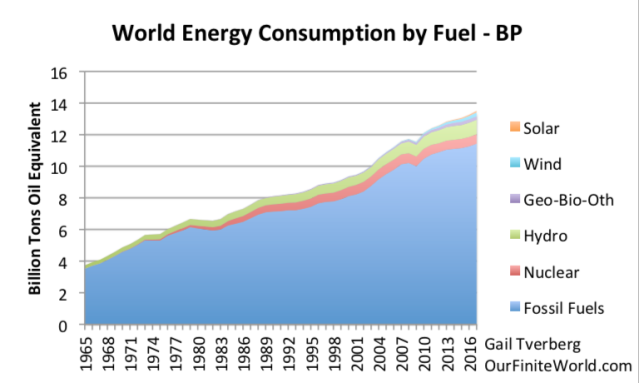

Furthermore, the share of the world’s energy supply that wind and solar provide is very low: 1.9% and 0.7%, respectively. They are shown in the almost invisible blue and orange lines at the very top of Figure 3. Fossil fuels contributed 85% of total energy supply in 2017.

Figure 3. World energy consumption divided between fossil fuels and non-fossil fuel energy sources, based on data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018.

[9] The world economy becomes very fragile as energy limits approach.

Energy limits seem to be affordable energy limits. Oil prices need to be high enough for exporting countries to obtain adequate tax revenue. In addition, oil producers need prices that are high enough so that they can make the necessary reinvestment, as fields deplete. At the same time, energy prices need to be low enough for consumers to afford goods and services made with energy products.

Much of the developed world’s infrastructure was built when oil prices were less than $20 per barrel, in inflation-adjusted terms. A rising price of oil will lead to a higher cost of replacing roads and pipelines. If these were built using $20 per barrel oil, even a current price of $40 per barrel would represent a significant cost increase. The world has experienced high oil prices for sufficiently long that we have collectively forgotten how low oil prices were between 1900 and 1970.

Most people know that the earth holds a huge quantity of energy resources. The problem is extracting these resources in a way that is both affordable to consumers and sufficiently high-priced for producers. Falling long-term interest rates between 1981 and 2002 allowed the world economy to tolerate somewhat higher oil and other energy prices than it otherwise could because these falling interest rates permitted ever-lower monthly payments for a given loan amount. For example, if interest rates on a $300,000 mortgage would fall from 5% to 4% on a 25-year mortgage, monthly payments would decrease from $1,753 to $1,584. The lower interest rates would allow more people to buy homes of with a given size of mortgage. Indirectly, the lower mortgage rates would permit additional new homes to be built and would allow more inflation in home prices. These benefits would at least partially offset the adverse impact of high energy prices.

Since the natural decline in long-term interest rates stopped in 2002, the world economy has become increasingly fragile; the Great Recession took place in 2007-2009 when oil prices spiked and long-term interest rates were already low by historical standards. It was only when United States’ program of quantitative easing (QE) was put in place that long-term interest rates could fall to even lower levels, helping the economy hide the problem of high energy prices a little longer.

The artificially low-interest rates made possible by QE have problems of their own. They tend to inflate asset prices, including both real estate prices and stock market prices. Thus, they tend to create bubbles, which are prone to collapse if interest rates rise. Artificially low-interest rates also tend to encourage investment in schemes with very low-profit potential. Artificially low-interest rates also encourage cross-border investments to try to take advantage of interest rate differences. If interest rate relativities change, the money that quickly would enter a county can almost as quickly leave the country, causing major fluctuations in currency relativities.

Regulators do not understand the role that physics plays in making the economy operate as it does. They assume that they, alone, have the power to make the economy behave as does. They do not understand how important falling interest rates are in creating growing demand for goods and services. The economy, since 1981, has spent most of its time with falling interest rates; the most recent part of this decline in long-term interest rates has been made possible by QE. These falling interest rates have played a major role in disguising the world’s long-term problem of rising energy costs. These rising energy costs are taking place primarily because the cheapest-to-extract resources were produced first; the resources that are left are have higher costs associated with them, for a variety of reasons, such as being farther away from the user, deeper, or needing more advanced extraction techniques. These issues have not been sufficiently offset by improved technology to keep extraction costs low.

US regulators now want to raise interest rates by raising short-term interest rate and by selling QE securities. They don’t understand that they are playing with fire. They feel that they will have more power if they can raise interest rates now, they will have the flexibility to lower them later if the economy should later slow excessively. They don’t understand how much of the world’s economy may really be a bubble, created by the decline in interest rates since 1981.

[10] The adverse economic outcome we should be concerned about is collapse, as encountered by prior civilizations when their economies hit limits.

The stories in the press have been so focused on oil “running out” and finding alternatives to oil that few have stopped to ask whether this is really the correct story. Instead of creating a new story, it might have been better to look more closely at history. Based on the historical record, collapse seems to have be associated with situations where populations have outgrown their resource bases. In other words, collapse can be considered an energy consumption per capita problem. The oil problem (and other fuel problem) we are facing today can be viewed as an energy consumption per capita problem, as well.

We know from research that has been done by Peter Turchin, Joseph Tainter, and others how collapse has played out in the past. The situation is different this time, however, because the world economy is very interconnected. Oil consumption depends on electricity consumption and vice versa. Our financial system is also extraordinarily important. For these reasons, a collapse may occur more quickly than in the past.

Differences Between My View and the Standard View

One of the big differences between the way I see the economy and the standard view of the economy is the answer to the question of “Who is in charge?” The standard view is that politicians and economists are in charge. They have all of the answers. The dire collapse outcomes that afflicted early civilizations could not possibly affect us. We are too smart. We know how to adjust interest rates correctly. We can even make QE available to lower long-term interest rates. We can also add more technology and other complexity than has ever been added in the past.

The answer I see to the question, “Who is in charge?” is, “The laws of physics are in charge.” Politicians play a fairly minor role in directing the fate of economies. If there is not enough energy available of the type needed (inexpensive and matching the current infrastructure), the economy may very well collapse. It is nature and the laws of physics that call most of the shots.

Another big difference between my view and the standard view is the observation that a decrease in oil supply (or total energy supply) affects both the supply and demand of energy. Because both supply and demand are affected, we don’t know which direction oil and other energy prices will move. They may move erratically, as interest rates are adjusted by regulators. A more complex model is needed.

Climate change becomes less of an issue in my view of the future, for several reasons. First, humans don’t really have very much control over the direction of the economy, so talking about anthropogenic climate change doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. The laws of physics that allowed human population to rise are also allowing climate change to happen. Second, we seem to be limited in our ability to use renewables to fix the situation. Furthermore, the possibility of collapse in the near future makes the various scenarios that hypothesize the use of large amounts of fossil fuels over many years in the future seem very unrealistic. Perhaps efforts to fix climate change should be focused in new directions, such as planting trees.

Help from Others

The subject matter of this post requires the knowledge of information from a wide range of academic areas. I could not have figured out all of this information on my own. I have been fortunate to have been able to learn from of a wide range of experts. Quite a number of academic groups have seen may articles, and invited me to speak at their conferences. In particular, I have had a long-term involvement with the BioPhysical Economics organization and have spoken at many of their conferences. I have learned much from Dr. Charles Hall, although at times I don’t 100% agree with him.

I have also learned from the many commenters on OurFiniteWorld.com. They form a self-organizing system of people from a wide range of backgrounds. Earlier, my involvement at TheOilDrum.com as “Gail the Actuary” allowed me to get acquainted with a range of researchers, looking at different aspect of the energy problem.

In future posts, I intend to expand further on the ideas presented in this post.

*Here I am using the term afford loosely. What borrowers can actually afford is the current required monthly payments.

Disclosure: None.

in energy statistics the past is prologue but doesn't determine outcomes. as technology improves developing countries CAN get electricity without carbon, for example in countries with lots of sun. We have a pick in India. And in western countries too even with oil prices falling it is not hard to fine alterrnative energy plays.

there are circumstances in hot developing countries where solar energy off the grid doesn't require subsidies. Where the background is right the same is true of wind power or tidal energy. In places like Iceland and Kenya geothermal power makes sense. It is wrong to assume that these alternatives to oil and gas won't grow more important. And I happen to think nuclear power also often is a suitable option.

Yes, nuclear may have its place. I just happened to be on the middle of a major earthquake out west and on the edge of another one. I think they should be avoided where the ground won't stay still.

Moon Kil Woong is right about the need to have a storage system for intermittant power like solar or wind. The sun doesn't shine for 24 hours and the wind doesn't always blow. I have a stock for this but it is a long-shot, a geothermal company from Nevada which also is developing storage systems, Ormat, ORA. It is not a global-investing.com pick because it is a US firm, and moreover its share has been beaten down over the volcanic eruption in Hawaii just down the road from its shut-in geothermal power plant. I take a long view.

Actually the world needs a cheap, dense, and hopefully safe electric energy storage system more than anything else. This would solve a lot. For energy production, the big hope is geothermal and/or fusion although modern nuclear power plants are much safer as well. Solar helps as does wind energy, but it won't solve our growing energy needs, especially without a dense efficient way of storing it.

I would not feel comfortable having nuclear power close to earthquake faults. Maybe it is just me. But there are other alternatives, but as the author says they are not necessarily enough to bridge the gap. So, energy affordability and proper pricing is very important to the economy. Americans are buying expensive large vehicles more and more. This could squeeze energy in the future.