Business As Usual Is Not An Option For Tackling Climate Change

Time is running short for decarbonising the global economy

Keeping global warming below 2 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average — the level scientists say is necessary to avoid climate change tipping points that could have potentially catastrophic environmental, social and economic impacts — requires capping the cumulative total of carbon emissions within the global ‘carbon budget’.

Key takeaways:

- Business as usual will soon exhaust carbon budgets that would limit global warming to under 2 degrees Celsius this century

- Much higher carbon prices and massive green investment is required to cut greenhouse gas emissions

- Investors must understand the profound challenge ahead and the impact on economies and markets

Keeping global warming below 2 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average — the level scientists say is necessary to avoid climate change tipping points that could have potentially catastrophic environmental, social and economic impacts — requires capping the cumulative total of carbon emissions within the global ‘carbon budget’.

Even if emissions were cut to zero from today, the rise in global temperatures since the pre-industrial period will continue to cause long-term climate change, including rising sea levels. Business as usual is no longer an option.

Carbon emissions will have to be reduced dramatically over the next decade and eventually to net zero. This will require a sharp increase in the price of carbon, which is yet to be reflected in the price of goods and services and in asset values.

The Amazon rainforest deforestation is a stark example of market failure from externalities – when the price of an activity does not fully reflect its costs and benefits. Land there is effectively economically worthless until it is cleared for farming. Yet its true economic value

lies in its function as the world’s most important carbon sink.

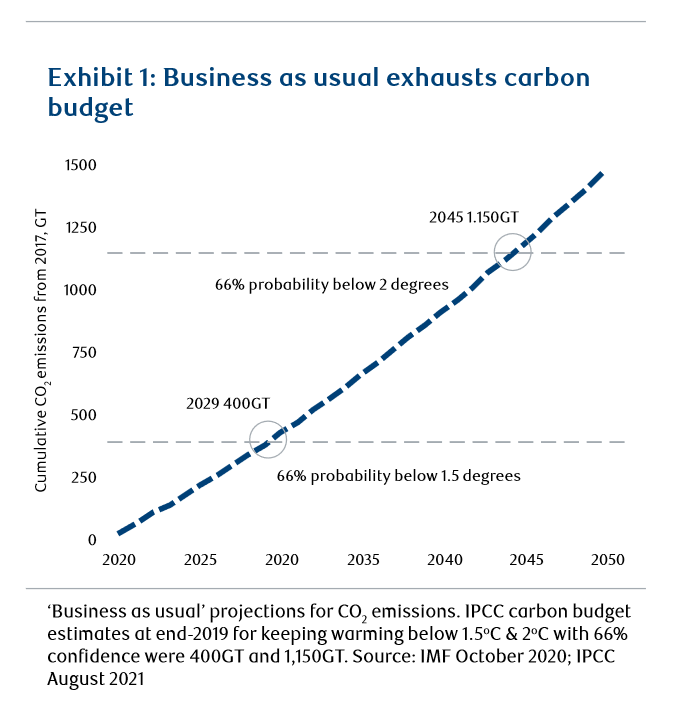

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that ‘business as usual’ will exhaust the carbon budget for keeping warming below 1.5 degrees by the end of this decade. Even the budget for keeping it under 2 degrees will be used up by 2050 (Exhibit 1).

World decarbonisation pledges don’t go far enough

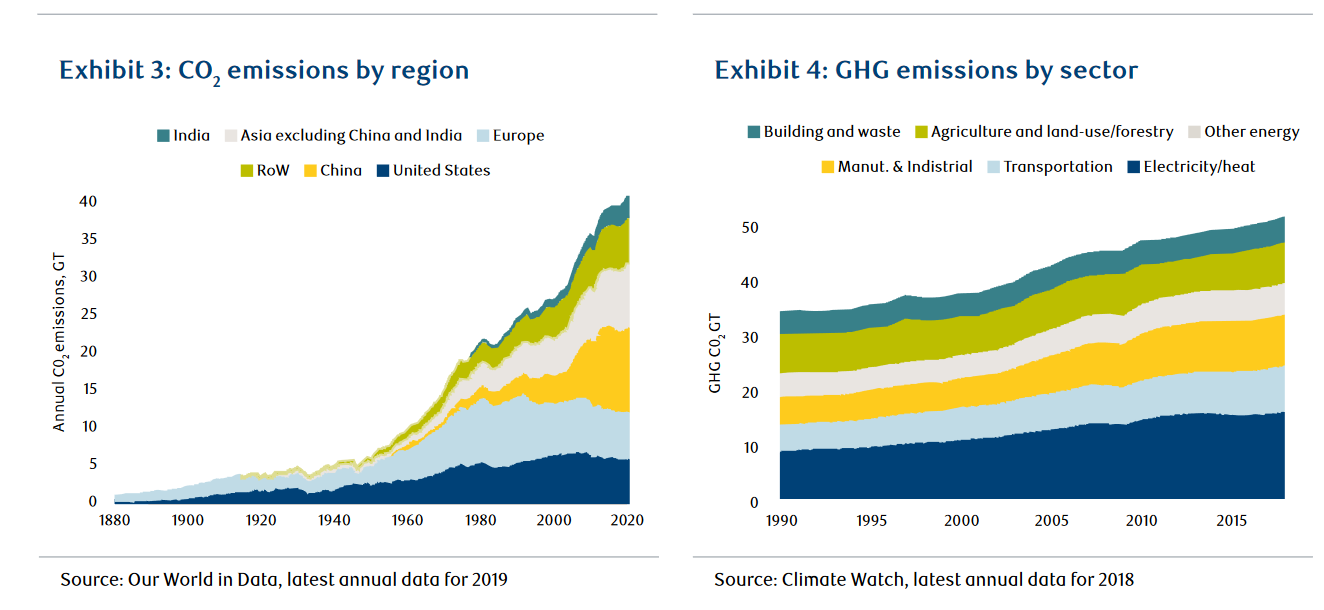

More than half of all annual greenhouse gas emissions come from China, the US, Europe and India. Falling emissions in developed economies are more than offset by increases in emerging markets, notably China, India and other Asian economies. That said, the developed world still accounts for most of the cumulative CO2 emissions since the pre-industrial era and of annual emissions on a per capita basis.

All signatories to the 2015 Paris Accord committed to carbon neutrality by the second half of the century – an extraordinary breakthrough. But developing countries have more time and flexibility reflecting their socio-economic development needs. India, for example, has pledged to cut carbon intensity of GDP by 2030 rather than cut emissions. Financial and technical support for developing economies is essential if they are to meet more ambitious greenhouse gas emission targets and mitigate climate change, a key objective of the recent UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow.

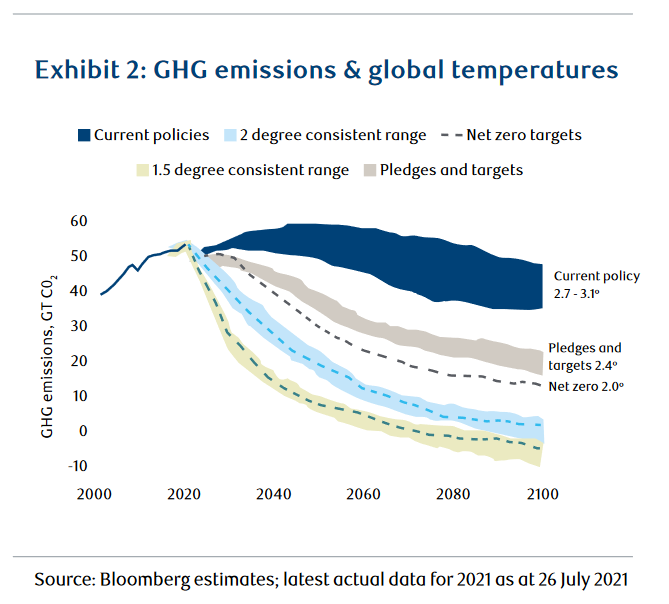

Independent scientific analysts Climate Action Tracker estimate that under current policies, the rise in global temperatures could approach 3 degrees by the end of the century. Even if countries honour current pledges and targets, the rise would be 2.4 degrees (Exhibit 2).

Some three-quarters of greenhouse gas emissions are energy-related, from electricity, heat and transport, and about one-fifth arise from agriculture (Exhibits 3 and 4).

Decarbonising the global economy will be costly and many options involve uncertainty:

- Planting forests will absorb CO2. But can this be done on a sufficient scale?

- Carbon removal technology is relatively new. Can it be scaled to have a meaningful impact?

- Protecting natural carbon sinks, such as the Amazon rainforest, which absorb about half of global emissions, has economic side effects.

Carbon taxes still too low

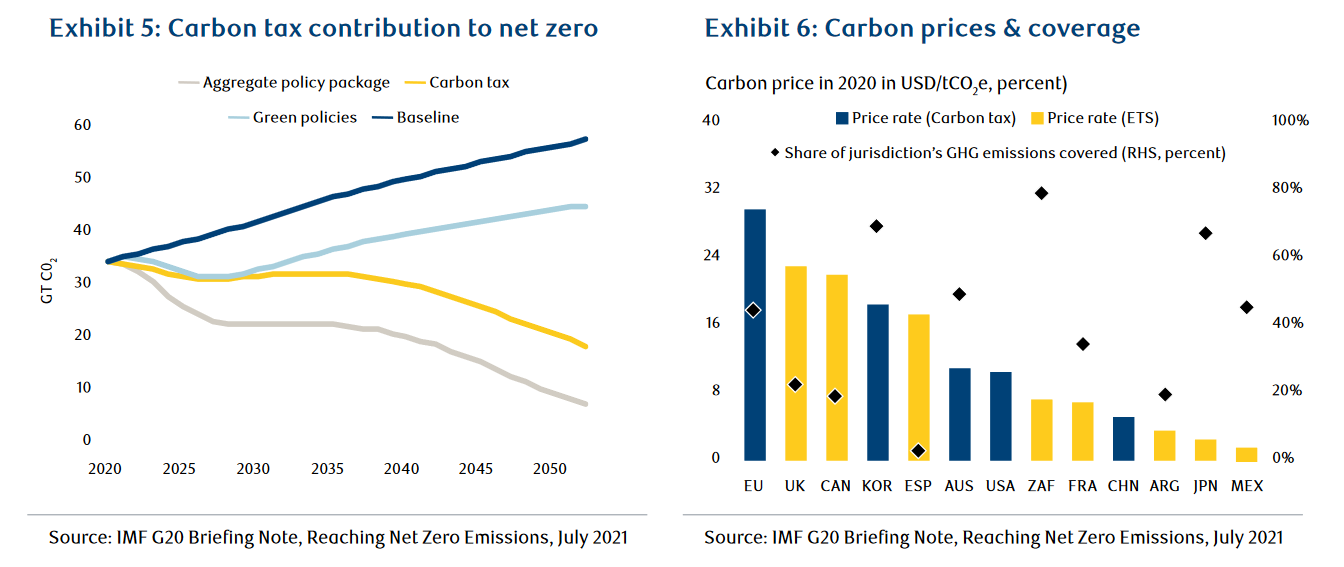

Carbon pricing is a cost-effective way of reducing emissions – principally carbon taxes and government-run emission trading systems (ETS) (Exhibits 5 and 6). Some countries may also impose carbon-related tariffs, but that risks sparking climate-related trade wars.

Carbon taxes and markets are becoming more widespread, but the price of carbon is still far too low to reallocate resources from high to low carbon economic activity and incentivise the scale of investment required to decarbonise the economy. Political resistance to higher carbon taxes, due to the impact it will have on household utility bills and transport costs, will impose even greater costs and higher global temperatures over the medium-term.

However, the IMF estimates that the economic hit from carbon taxes will be more than offset by the economic gains. Carbon taxes can do the heavy lifting of reducing emissions while green investment can stimulate technological innovation and will gains. Carbon taxes can do the heavy lifting of reducing

emissions while green investment can stimulatetechnological innovation and will generate jobs, offsetting the costs of transitioning to net zero. Tackling climate change and the transition to a low carbon economy will be the key investment theme of the next decade and beyond. Those that dismiss climate change as a long-term issue beyond their investment horizon will fail to benefit from the opportunities it will present as well as the risks it presents.

Disclaimer: For Bluebay Assest Managements' full disclaimer, please click here.