Simplifying The ‘Fed Model’ To Determine Fair Valuation

Image Source: Pexels

Investors have plenty of choice in what to buy—whether it be stocks, bonds, real estate, gold, you name it. They’re buying these assets with the expectation that they’ll be worth more in the future.

If investors are thinking rationally (a big assumption), they should demand a higher return for taking on higher risk.

At the risky end of the spectrum are stocks. Stocks are risky for many reasons, one of which is their position in the capital structure of a company. They are the most junior claim after all other creditors. There is no guarantee or assurance that you’ll get your money back after buying stocks. Therefore, investors demand a return for taking on this risk. As an investment, stocks are not risk-free.

At the other end of the spectrum are US government bonds and bills. This is risk-free investing. The US government will always pay its debts and interest.

Returns on Stocks and Bonds

The Fed model, a market timing tool for determining whether the US stock market is fairly valued, looks at the relationship between these two investment choices: stocks and US government bonds. It does this by comparing the return profile, based on an equation that compares the earnings yield of the S&P 500 with the yield on 10-year US Treasury bonds.

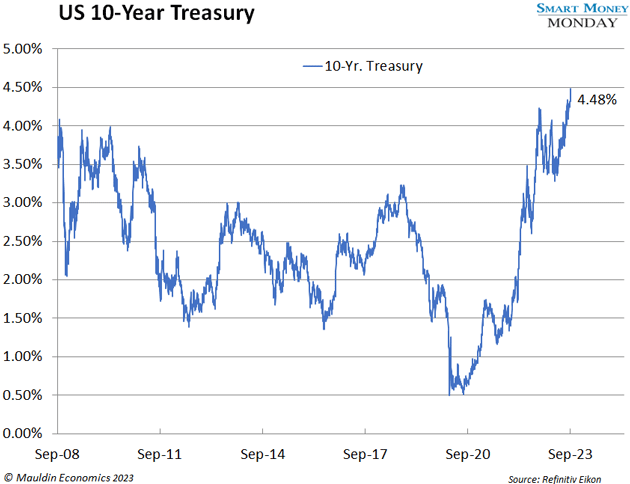

The return on a 10-year Treasury bond is simple. What’s the interest rate? Buying a 10-year US Treasury bond today at par will pay around 4.48% per year for 10 years. That’s your return.

And interestingly, right now, 4.48% is one of the juiciest returns we’ve seen for a 10-year bond in over 15 years.

The return for stocks is a little trickier. It requires some estimation—or rather, using what other analysts are estimating.

Looking at the S&P 500, it currently trades at a forward multiple of earnings of around 18.5X (i.e., it trades for 18.5 times what analysts are forecasting for earnings over the next 12 months). Inverting this, the S&P 500 trades for an earnings yield of 5.4%.

The Fed model then takes these two data points and compares them. Right now, investors are only getting around 1%—or 100 basis points—of excess returns by purchasing the S&P 500. It’s really that simple of a concept.

The Fed model further goes on to suggest that stocks become overvalued when the 10-year yield equals, or exceeds, the S&P 500 earnings yield.

Right now, we’ve seen some multiple expansions on the S&P 500. But what’s really compressed this spread between stocks and risk-free bonds is the bond piece of the formula.

The rate on US 10-year government bonds has soared from under 1% to 4.48%. Does it have further to go? Maybe.

The Fed model today suggests that stocks—specifically, the S&P 500—are approaching overvalued levels.

The Counterpoint to the Fed Model: the ’90s

Let’s look back to the 1990s…

The 10-year US Treasury bond had a higher interest rate than the S&P 500 earnings yield for much of the decade.

The S&P 500 traded at around 20X earnings for much of the 1990s. In contrast, the 10-year Treasury had a yield of around 6.5%.

An investor buying a 10-year US government bond in January of 1990 clipped an 8.6% coupon for the next 10 years. That same investor who bought the S&P 500, which, again, was signaled as “overvalued” based on the Fed model, outperformed bonds in a dramatic fashion.

From the beginning of 1990 to December 1999, an investor saw their S&P 500 investment grow by over 300%. On a compounded basis, that penciled out to over 15% per year.

So again, despite the Fed model signaling overvaluation, stocks still outperformed.

Today, There Is an Alternative

The Fed model is an interesting theoretical exercise. But for the 1990s, it just didn’t matter.

The big picture, the takeaway here is that finally, after 15 years, we can get a decent return on risk-free government bonds. Again, the 10-year bond is at its highest level since 2007.

The narrative post-financial crisis was TINA: “There is no alternative.” That is, investors must buy stocks if they want to get a positive return.

Today, there is an alternative. Bonds are finally interesting, and they deserve a place in a balanced investment portfolio.

More By This Author:

Is This Dog Of The Dow A Buy?Catastrophe Bonds - Are They Worth The Risk?

Is This Beaten-Down Utility A Buy?