Why Does Demand Affect Prices?

Unfortunately, macroeconomists lack a common framework for thinking about how the macroeconomy works.

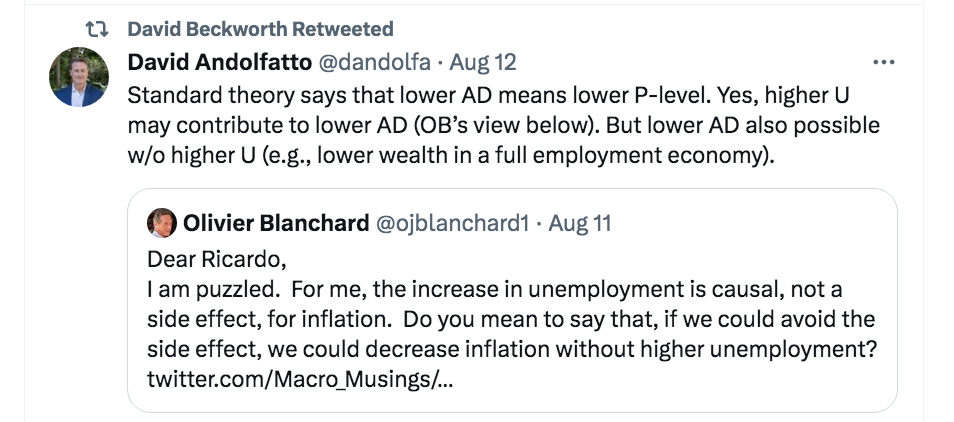

David Beckworth directed me to a tweet that nicely illustrates this problem:

First, let me agree with Blanchard on one point. I would certainly expect a decline in inflation to be associated with a rise in unemployment. But his claim about the causal mechanism seems so strange to me that I even have trouble thinking of a way to explain why we disagree. If a student asked me “why does Blanchard think higher unemployment would reduce inflation?” I’d have trouble answering the question. That doesn’t mean he’s wrong, (he’s a far more distinguished economist than I am), it’s just that our approaches are so different.

Instead of starting with a sort of extreme Chicago/monetarist argument, let me start with an idea that once had strong support among Keynesian economists—incomes policies. Back in the 1970s, left-of-center economists in places like the US and Europe favored “incomes policies” (basically wage/price controls, with an emphasis on wages) as a way of reducing inflation. They didn’t believe this policy would do the job all by itself, rather they argued that it would allow other policies that slowed the growth in aggregate demand to reduce inflation with less of a side effect of high unemployment. So why did they believe this?

At the time, I assumed that incomes policy proponents bought into the “sticky wage/price” theory of macroeconomics. This is the idea that demand shocks have real effects because wages and prices are sticky in the short run. (Some argue that in the long run money is neutral and output returns to a natural rate. But that claim has no bearing on this post.)

So Keynesians seemed to believe that demand-side policies that reduced the growth rate of nominal spending would involve more output and less inflation if wages and prices could somehow be made more downward flexible. Incomes policies (if effective) were supposed to do this:

Lower NGDP —> Lower inflation & stable output

Here I have no interest in the question of whether incomes policies were effective; rather I’m focused on the mechanism by which they were supposed to work. It seems to me that that mechanism is completely at odds with Blanchard’s view of the problem.

I agree with Ricardo Reis, we should think of unemployment as an unfortunate side effect of policies that restrain demand to control inflation:

1. Contractionary demand side policies –> falling nominal spending

2. Sticky wages and prices

3. Reduced inflation as well as lower employment/output

Aggregate nominal spending is P*Y. If nominal spending falls by 10% and prices only fall by 4% (due to sticky wages and prices), then output and employment will necessarily decline. But that employment decline doesn’t seem causal.

When people talk of a causal role for unemployment I see:

1. Lower employment

2. ???

3. Lower inflation

To some people, that causal relationship might seem obvious. But to me it seems much more natural to see unemployment as a side effect. If wages and prices were completely flexible, it’s hard to see how changes in nominal spending would have any real effect on employment or output. In that case, what would be the causal mechanism between nominal spending and inflation?

You might argue, “But wages and prices are not completely flexible in the real world.” Yes, but that’s not the point when trying to understand the causal mechanism. If it were really true that unemployment is the causal mechanism, then in a world where wages and prices were 100% flexible and the economy always stayed at the natural rate there’d be no way to slow inflation with contractionary monetary policies. Does anyone believe that?

Recall that a lower price level is equivalent to a higher value (purchasing power) of money, the unit of account. Blanchard is basically saying that the only (demand-side) mechanism by which we can give money more value is by creating unemployment. Now consider a microeconomic analogy to his claim:

Assume a shock to the apple market that raises the equilibrium price of apples, such as a change in consumer preferences or a crop failure. That rise in apple prices might be associated with a situation where grocery stores were temporarily out of apples. Maybe they didn’t immediately raise the posted price, and consumers exhausted the existing stock.

Even if there were a temporary apple shortage, I think it would be weird to view the shortage as causing the higher apple prices—it was the reduction in supply an/or the increase in demand that caused the higher apple prices. There might be a temporary shortage if apple prices were sticky. But I can also imagine a scenario where apple prices were flexible, and there were no shortages during the transition to higher prices. In that case, in what sense would shortages be the causal factor for higher prices? You can reverse this example for surpluses of apples when the price declines.

When overall inflation declines, it’s the reduction in AD and/or the rise in AS that causes the decline. Unemployment might rise as a side effect, but it’s hard to see how it’s the causal factor. It’s an unfortunate side effect of sticky wages and prices leading to disequilibrium. But disequilibrium doesn’t cause the lower inflation; indeed inflation would actually fall faster if the real economy stayed at equilibrium when nominal spending slowed. In that case, a sudden 10% fall in NGDP would immediately reduce prices by the full 10%.

Here’s another example. Apartment rents often decline when there are a lot of vacancies. But building a lot of new apartment buildings should reduce rents even if the vacancy level never rises. Vacancies aren’t a causal factor; they are evidence of a market out of equilibrium. It’s the supply and demand for housing that drive the process.

Even if the correlation between lower inflation and higher unemployment were 100%, if wages and prices were always sticky, it still doesn’t make unemployment causal. If you told me that 100% of people with Covid had a fever, I still wouldn’t believe that fevers cause Covid.

Update: Ricardo Reis has an excellent thread on this issue.

PS. I have a related post at Econlog.

PPS. As an aside, the 1971-74 incomes policy failed in the US because policymakers failed to enact contractionary fiscal and monetary policies during the control period. So the proposed policy was never actually tried. NGDP growth remained very high and (not surprisingly) inflation rose after the controls were lifted. I’m not a fan of incomes policies, just pointing out that this outcome has no bearing on the issues in this post. I mentioned incomes policies only to better understand the thought process of its Keynesian proponents.

More By This Author:

Bubbles Don't Exist - Example No. 761

A Tale Of Twin Cities

The Actual Phillips Curve