The Inflationary Energy Transition

Ominously for President Biden, opinion polls consistently show voters are unhappy with his economic stewardship. The surge in inflation in 2022 didn’t help, but after believing it to be transitory the Fed responded and it’s now back down.

Wednesday’s 3.4% CPI figure isn’t yet at the Fed’s 2% target but is close enough that the difference shouldn’t be discernible for the typical consumer.

And yet 22% of voters identify inflation/prices as their most important issue, according to a recent Brookings poll. Inflation feels higher than 3.4% to many people.

Part of the reason is that inflation calculations assume a basket of goods and services of constant utility. This anodyne term means the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) adjusts for quality improvements. A better iphone gives you more utility. More iphone for the same money is a price reduction under this construct.

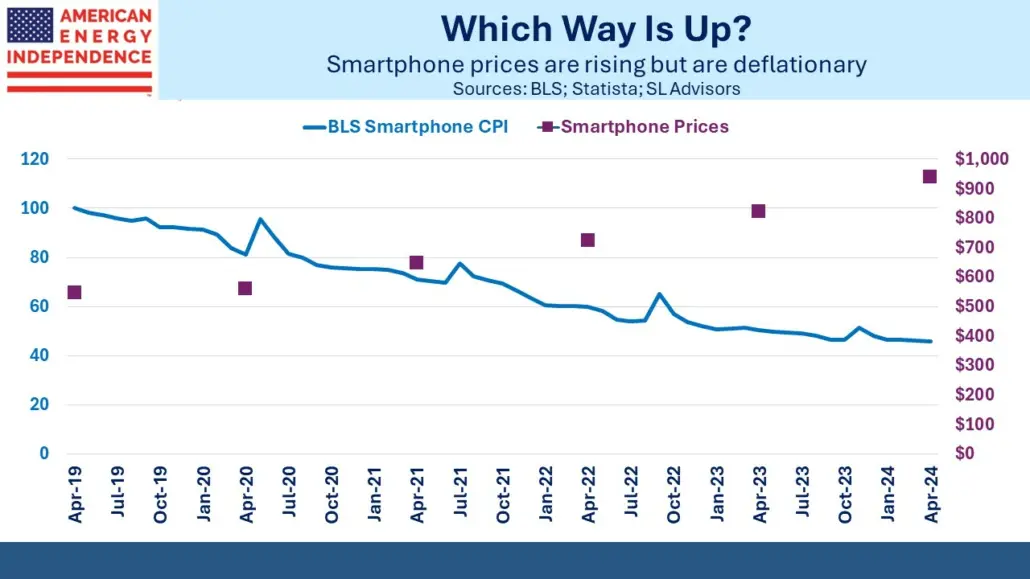

The chart shows the difference. Average smartphone prices are up 72% over the past five years. But adjusted for their enormous quality improvements, the BLS find that they’re down 54%. They’re called hedonic price adjustments.

This is an extreme example, but it illustrates the point. Household income isn’t up 72% over the past five years, and since it’s impossible to live without a smartphone they are commanding an increasing share of disposable income. We’re all benefitting from increased utility since today’s smartphones are better, but few of us recognize that increased utility or can figure out what to do with it.

It just means that what the BLS is measuring doesn’t correspond with how we experience the purchase of goods and services. We have written on this subject before (see Why You Shouldn’t Expect A Return To 2% Inflation, Why It’s No Longer Enough To Beat Inflation and Why You Can’t Trust Reported Inflation Numbers).

The energy transition is inflationary. It’s taken a long time for this to become clear because Democrats have long clung to the shibboleth that moving towards renewables would create well paid union jobs while exploiting the fact that solar and wind are cheaper than natural gas.

It’s now clear this was never true.

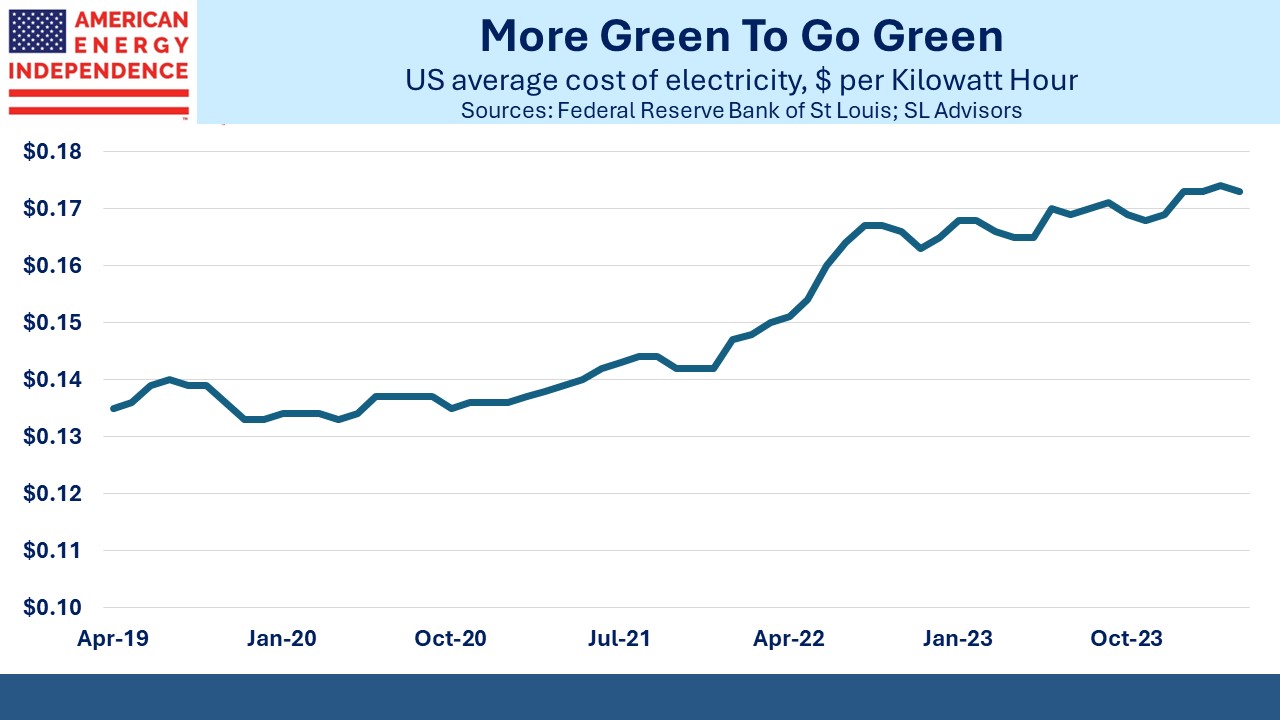

US electricity prices have moved sharply higher over the past two years, from 15.1 cents per Kilowatt Hour to 17.3 cents.

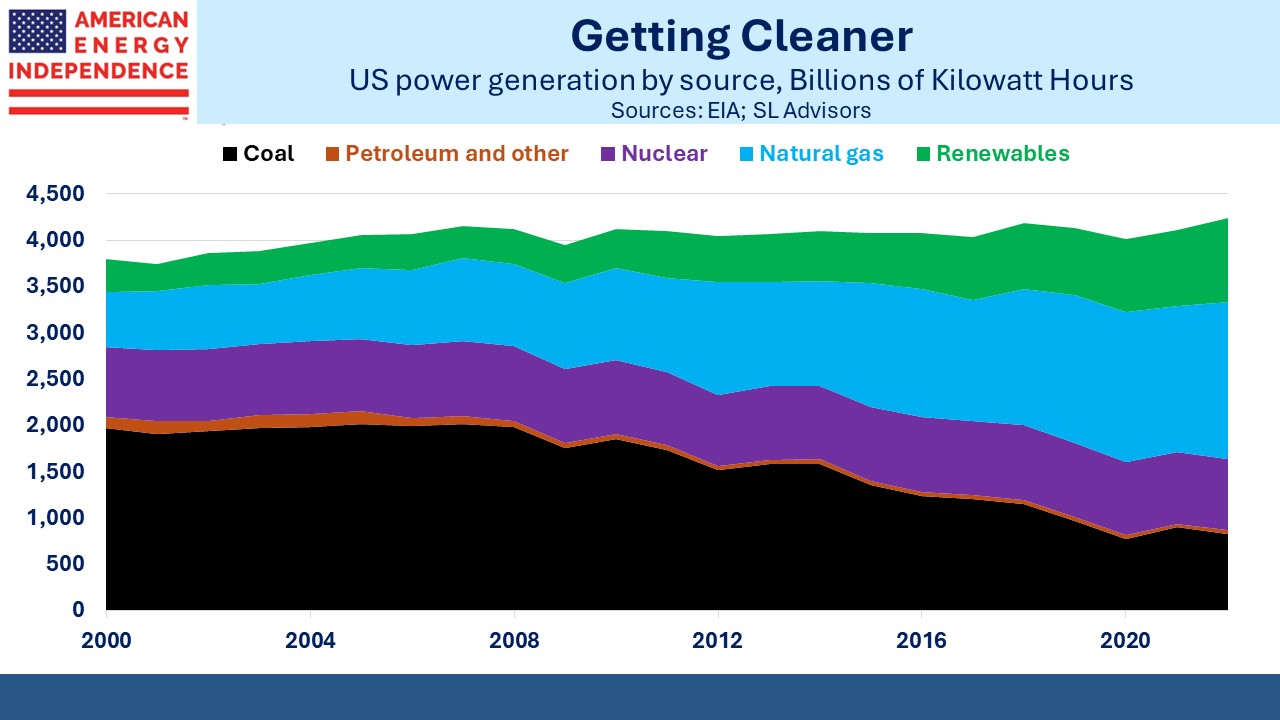

The trend over the past couple of decades has been for natural gas to displace coal, because it’s cheaper. Renewables have been gaining market share as a policy choice, often driving additional demand for natural gas to compensate for their intermittency.

Incidentally, the relative stability in annual electricity consumption of around four terawatt hours since 2000 is about to change as data centers for AI come online (see AI Boosts US Energy). This will also push natural gas demand higher over the next few years.

More weather-dependent electricity requires increased spare capacity for when it’s not sunny or windy. This reduces the capacity utilization of the grid (see Renewables: More Capacity, Less Utilization and Management Stumbles; Getting Less From Our Power Sources).

The energy transition causes inflation directly through higher electricity prices. The Inflation Reduction Act, which does the opposite of its title, is a huge source of energy subsidies. It’s intended to reduce CO2 emissions and is likely to cost over $1TN in fiscal stimulus.

Paying more for energy in order to reduce emissions isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Democrats have opted not to argue that green costs more because it’s good for you. But achieving lower CO2 underpins public policy in OECD countries to varying degrees. An economist might say that this brings greater utility. Carbon-free electricity that costs more might even cost less following a hedonic quality adjustment from the BLS.

It’s tempting to predict that the BLS will apply their statistical magic to energy prices, ameliorating price increases to reflect greater utility (ie lower emissions). A Democrat White House would surely love this, although it’s too late to make an impact before the election. But it’s unlikely, because the value of reduced emissions is unknown, and it would too easily appear politically motivated.

But it could provide a reason for the Fed to relax their 2% inflation target. There’s not much point in spending $TNs to reduce emissions if monetary policy responds by increasing the cost of capital for the long-lived assets the energy transition requires. Several years ago the Fed acknowledged an asymmetric inflation target, in that they’ll now tolerate it above 2% for a while. There’s no chance the Fed would then seek <2% inflation to bring the average lower. So we should already anticipate inflation above 2% over the long run.

This will also ease the burden of our looming fiscal catastrophe. The baby-boomer driven climb up the CBO’s steep wall of indebtedness has already begun. Tight monetary policy is making it worse via higher interest expense on outstanding debt (Our Darkening Fiscal Outlook).

Prudence dictates that investors plan for the Fed to accept inflation generally above their 2% target. All we’re waiting for is to see how they justify it.

We have three have funds that seek to profit from this environment:

More By This Author:

A Look Back At Energy Transfer

Pipeline Earnings Keep Climbing

Discussing Energy In America’s Heartland