The Continued Sorry Math Of Bonds

Last week an investor asked us what he should do with his bond portfolio.

We started with a monthly newsletter in January 2010, which over the years evolved to a twice-weekly blog. The poor outlook for bonds has been a regular topic almost from the beginning. Through descriptions such as “returnless risk” and “pigmy yields” we have sought to convince investors what a losing proposition they face in fixed income. The partners of SL Advisors have not personally held any bonds since the firm was founded in 2009.

In a blog post in October 2011 (see The Sorry Math of Bonds) we made the case for replacing a bond portfolio with a 20/80 barbell of stocks and cash. Back then the 2% dividend yield on the S&P500 was close to the yield on ten-year treasuries. The logic of preferring stocks is that their dividends grow over time, and their tax treatment is better. These two features mean that the investment return on $100 in a ten-year bond yielding 2% can be achieved with a lot less in stocks – we suggested $20 back then, with the rest sitting in treasury bills. It’s not complicated to build a model comparing the two – the most sensitive assumption is that dividend yields are unchanged at the end of the ten-year investment horizon.

Other blog posts on the topic include A New Approach to Bonds, Stocks Are the Cheapest Since 2012 (see 3rd and 4th charts) and Stocks Are Still A Better Bet Than Bonds (see 4th chart).

Naturally, our response to this investor’s question was to dump bonds and create a bond-like portfolio of stocks and cash. We’ve been recommending this for over a decade.

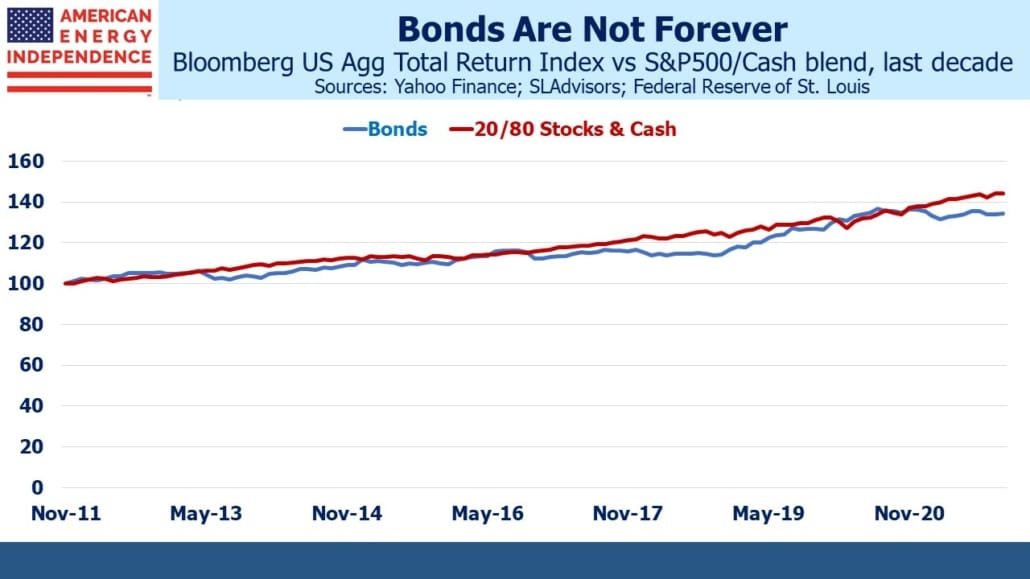

The charts show how this approach has worked. Since November 2011, bonds (defined as the iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF, AGG, which tracks the Bloomberg US Agg Total Return Index) have returned 3.0% p.a. This is considerably better than we would have predicted a decade ago and not something investors should expect over the next ten years. The S&P500 returned 16.2% p.a. over the same period. The 20/80 portfolio delivered 3.7% p.a., assuming the cash portion was invested at the Fed Funds effective rate. Cash didn’t always earn close to 0% over the past decade. Next year cash balances should once again start to receive a modest return.

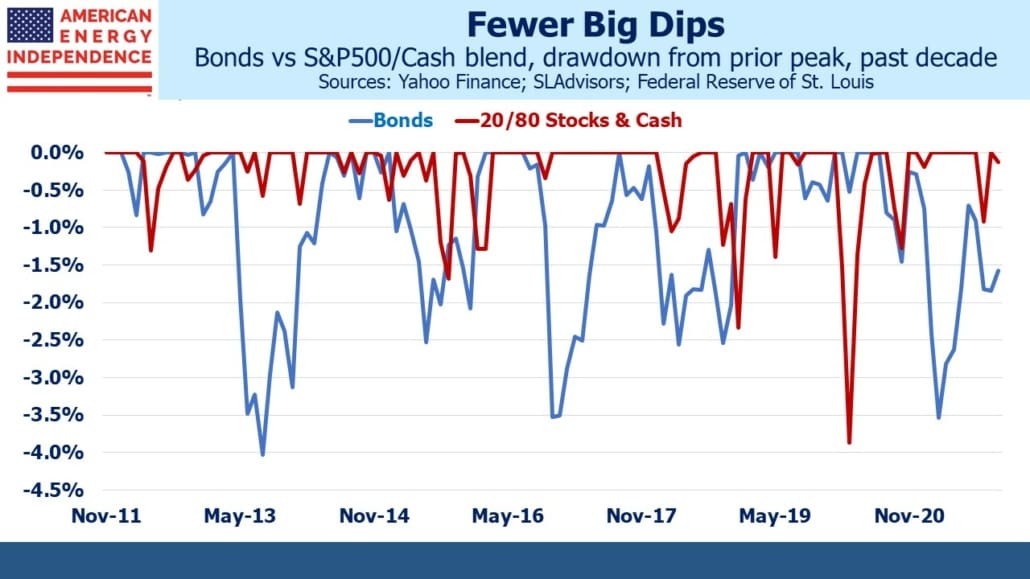

The two portfolios tracked each other quite closely as well, although the stocks/cash mix was marginally less volatile. Its monthly returns had a standard deviation of 0.8%, versus 0.9% for bonds. The maximum drawdowns were also similar. Bonds suffered a 4.0% loss of value in 2013 during the “taper tantrum,” an experience that is behind the current FOMC’s measured (we would say very overdue) withdrawal of their bond buying program. The stocks/cash portfolio fell 3.9% from its previous high in March 2020 because of COVID. Bonds suffered two other drawdowns in excess of 3%, while the stocks/cash portfolio did not.

The 20/80 stocks/cash portfolio beat bonds with less risk over the past decade. Remember, past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

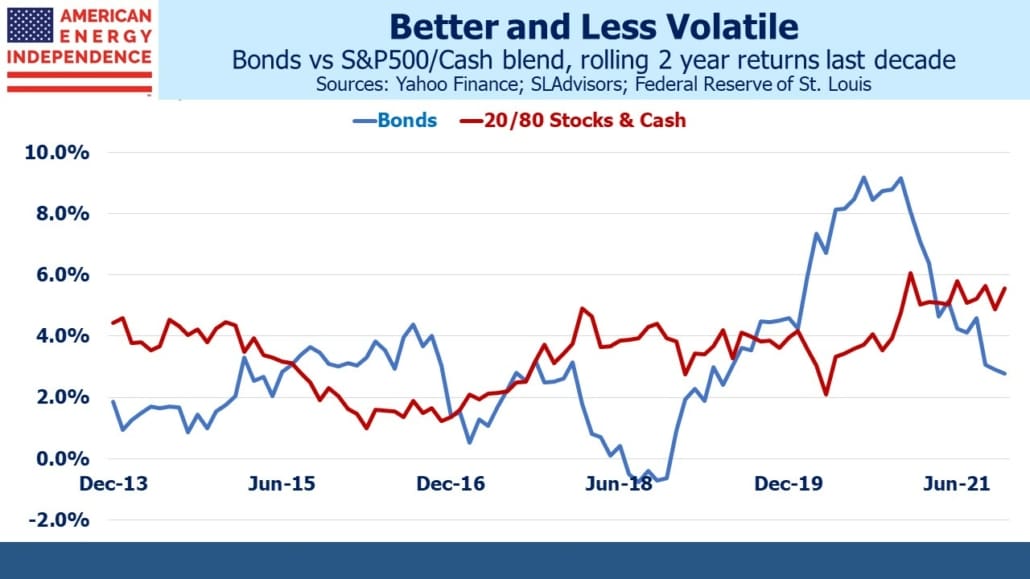

Although monthly returns had similar volatility, rolling two-year returns varied more for bonds than their synthetic substitute. The point of a fixed income allocation lies not just in its lower risk profile but also its diversification. Clearly, a 20/80 stocks/cash portfolio will be correlated with stocks and provide no diversification, albeit with 80% less volatility.

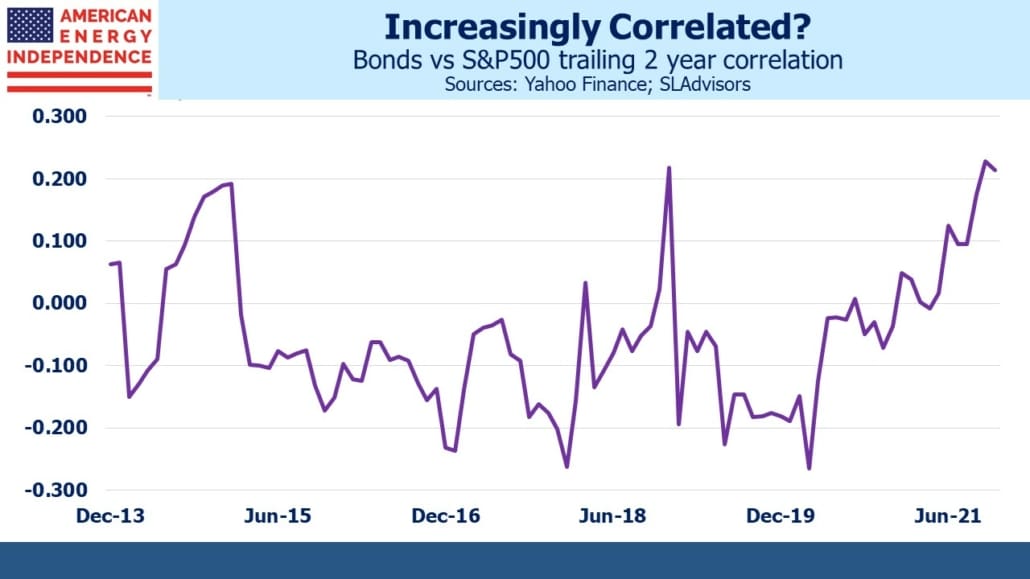

Over the past three years the correlation between stocks and bonds (calculated using trailing two years’ monthly returns) has trended up, although it remains low. Diminutive bond yields have underpinned equities for years. A sharp drop in bond prices remains a major risk for stocks, even if it’s hard to predict what might cause that. In such circumstances, a conventional stock and bond portfolio would likely not enjoy much diversification.

In my 2013 book Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors I looked at the stocks/cash substitute for bonds in more detail (Pp 195-8).

The case for replacing fixed income with the stocks/cash barbell is stronger today than it was in 2011 when we first suggested it. US government bond yields are held down by $TNs of demand from return-insensitive buyers such as foreign central banks, and others with inflexible mandates such as pension funds. With real yields of -1% dragging down returns throughout fixed income, the only prospect buyers have of a decent return is if these trends continue. It’s a bit like owning gold (GLD) — you’re hoping someone else takes you out at a sillier price than you paid.

The conventional belief that investors should retain a fixed income allocation is being undercut by negative real yields. The government’s response to COVID shows that massive fiscal stimulus will be deployed against a recession, and the Fed’s balance sheet will be used to monetize debt. This new paradigm makes inflation more likely than deflation following an economic downturn. It’s time to leave the bond market to those not in need of a return on their investment.

Disclosure: We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that ...

more