TBT: My Best Inflation Play Ever

Inflation Today

The largest holding in our Investor's Edge model portfolio is an ETF that I believe is guaranteed to rise in the coming years. "Guaranteed" is a strong word. Here is why I believe it to be accurate:

The ETF that I am talking about is an inverse ETF on US Treasury bonds. These are not like the potentially dangerous inverse equity funds, which reward you if stocks decline but punish you if stocks soar. These ETFs move more slowly, but I believe while their rise might be slow, I see it as both steady and inevitable. My personal favorite is the ProShares UltraShort 20+ Year Treasury ETF (TBT), a 2x leveraged short ETF.

TBT's approach is the pinnacle of simplicity. Instead of holding 20-year US Treasury bonds, this ETF enters into Treasury Index Swaps with investment banks like Societe Generale, Citibank, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. These swaps give the ETF the opportunity to sell back positions to these investment banks at a profit if the bonds fall.

I have chosen this ETF because it is leveraged 2x to the underlying investment. That is how confident I am that inflation will once again rear its ugly head. If, in the interim, all the jawboning by Fed and Treasury talking heads makes this ETF cheaper, good for me. I will buy more.

What is in it for the investment banks engaging in this swap? They receive all the interest on the bonds and a fee from the counterparty to the swap - that would be, in this case, TBT. The big investment banks are betting that rates will not rise too far or too fast.

This arrangement allows the holders of this ETF to benefit if rates rise (or suffer if rates fall.) As new debt is created at higher rates, these older Treasury bonds, to remain relevant, must pay the same effective yield as the new ones. By being "short" the 20-year Treasury bonds, this ETF makes money if rates rise, meaning prices of these bonds must fall.

I think those who do not believe rates will rise are blind to the massive amount of Treasury and agency bonds that must be issued to fund the current and future deficits that result from the spend, spend, spend (then tax) policy we currently see from our national government.

The investing theme here is the very model of simplicity. If US inflation declines, these funds will lose value. If US inflation continues to rise, TBF will rise as well.

I accept that the Fed et al may be correct that "the current" inflation fear is transitory. That is, it may last only until the supply chains expand their pipelines of product and more people rejoin the labor force, removing wage inflation.

But over the longer term of months and years, I fully expect my Anti-Treasury investment in ETFs like TBT to fully protect my purchasing power and my portfolio.

(By the way, if you prefer no leverage other than the natural decline of the dollar, the ProShares Short - not "UltraShort" - 20+ Year Treasury ETF (TBF), is more for you.)

It is eminently fair to question Fed Chairman Powell and Treasury Secretary Yellen for their remarkable inability to speak the Queen's English. For some reason, they cannot seem to formulate sentences which ordinary, extraordinary or off-the-charts geniuses can readily understand. The obfuscation may be intentional. Perhaps there are special postgraduate courses for economists who must also function as politicians which teach them to bloviate and to muddle and befuddle. (Whereas politicians have the much easier job; bloviation seems enough for them.)

Still, in this case, the continued emphasis on the word "transitory" in the pronouncements from Chairman Powell and most of his colleagues may indeed be correct -in the very short term. Inflation was once described by Milton Friedman as "too much money chasing too few goods." In the current case, goods stopped being produced when Covid-19 ensured no one was buying anything but essentials. In addition, too much money was and still is being distributed as a perverse incentive leading to jobs going unfilled.

Dr. Friedman's analysis of "too much money chasing too few goods" was a gem of understandability. In today's case, there are in fact two very strong components which might provide greater granularity into our current concern with inflation.

The first of these is supply constraint. This one is clear to us all. When we feared the worst before the heroic effort by pharmaceutical companies to protect us against this virus, we reined in our spending. (Except, of course, for toilet paper. For that, we not only spent like drunken sailors but fought like them over the last roll of Charmin.)

By not eating out, restauranteurs had to lay off staff and stop or radically slow their purchases from food companies. Farmers might not have planted as many acres. Travel companies went out of business or scaled back hugely. Fewer cars were produced. Fewer boats. Fewer airplanes. Fewer barbecue grills, beach balls, bingo machines and bikinis. Now we want all of that again, and we want it now. (Well, maybe not bikinis. There may be a delay there until the "Covid 15" extra pounds come off.)

We have the money, thanks to all the stimulus largesse, and we are now chasing those "too few goods." This will shake itself out, and soon. Factories have reopened, manufacturing lines are being re-started, and goods from all over the world are slowly making their way to the places with willing and anxious consumers. The supply constraint will one day be behind us and, as we approach that date, this one key component of the current rise in inflation will be no more. In that sense, this may mean that this surge in inflation may well be "transitory."

The other is wage inflation. Wage inflation means employers are not able to hire anyone who will work for only the cost-of-living difference from the same wages they worked for a year ago. After all, they have become accustomed to making so much money by not working, they are now demanding a premium, not just over last year's salary but also a hefty chunk over what they can now make by spending the day playing video games and yammering on Facebook.

A local restaurant owner tells us he has raised wages to a minimum of $18 an hour to wash dishes and still can't get anyone to apply for the job. (Heck, I did it at Pearl's Supper Club for $1.75 an hour and all the French Fries I could eat. Of course, in today's dollar terms, that would be about $12.50 an hour. But at $12.50 an hour, no one is willing to take the job.) His only alternative, having survived the pandemic, is to now - now, after all that belt-tightening! - close his doors or raise prices yet again. Dining patrons, already upset over how much everything costs, will not eat there if he raises prices one iota. He is caught between a rock and a hard spot. However, I see this dynamic changing soon, as well.

Once stimulus and unemployment benefits and all the other special benefits and stimulus begin to run out, people might be willing to work for merely good, but not necessarily corner office, wages. How long has it been since someone said, "I'll take any job that pays a fair wage?" We may be forced to do so if we still enjoy eating and having a roof over our heads. For this reason, I see wage inflation also subsiding significantly in the short to intermediate term, lasting until we face the inevitable reckoning for printing all that "free" money.

Yes, But What Comes After This Transition?

There will still be some mitigating factors to keep inflation a little restrained for a little while. For instance, workers now understand they do not need to live in an expensive urban residence in order to have a job with a company headquartered in that city. All these fancy upgrades to urban infrastructure (more trains, more subways, more highway lanes, more roads torn up for years,) will likely be provided to a smaller and smaller urban population base. This will allow those who opt to move to a lower cost of living locale to raise their savings rate and blunt inflation at the "personal" level.

But at the national level? The only way the federal government can repay the enormous debt they are saddling you, me, our children, and our children's children with, is to destroy the savings of many bond investors, especially those who buy long term US Treasuries. Sure, you will receive, let us say, 1.5% or 2% a year for 20 years, but along the way, bread may rise 5%, milk 7%, hamburger 9%, and so on.

The Fed wants inflation. The Treasury needs inflation. The US must pay all those debts we incurred as a nation with dollars that are worth less and less with each passing year. A $100,000 face value 20-year Treasury bond purchased today will certainly pay back $100,000 on maturity date - but that $100,000 might then buy a 10-year-old car and a loaf of bread.

My guess is that you will be fine buying a little of this and selling a little of that over the next few months, just as you are likely doing now. But you must remind yourself daily that you are doing so at ever-increasing valuation levels. I have a number of different sectors I favor and have placed them accordingly in our Investors Edge model portfolio. All are doing well.

But there is the other action I am taking that I keep adding to whenever there is a pullback. I take some of my profits and place them where I believe I can protect them even after the market enters its next decline.

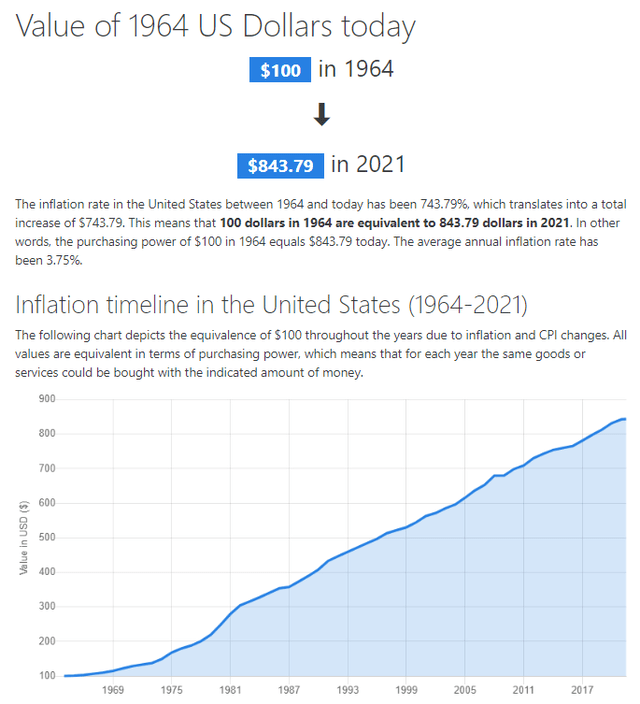

Markets go up and markets go down, but inflation is the one force I can depend upon to go up over the long term. We might soon enjoy a "transitory" abatement for a few months. Nevertheless, it will resume. It always does. Here is a chart of US inflation since 1964, the year of my after-school job pearl diving at Pearl's Supper Club on a lonely stretch of road between Las Vegas on what was then the little burg of Henderson, Nevada.

Source: USD Inflation Calculator - US Dollar (1956-2021)

The Buy I Make Regularly

I am quite pleased with the holdings in our subscribers' model portfolio. I am not ready to pull away from the current market with the holdings I consider perfect for the current times. But I need more than just that. I need to be thinking about what comes next.

Since I know I can trust my government to cheapen our money in order to repay borrowers less in real terms 20 years down the road, I also regularly add to my position in TBT, which I have dubbed "The Anti-Treasury."

(While I may have coined the name, the investment idea was first presented to me by my colleague Gray Emerson Cardiff, editor of the Sound Advice investment letter, one of the best-performing and best-written in the country.)

Some investments have a zero or negative correlation with the stock market, which in times of severe volatility and turmoil make them worth considering solely for that reason. However, if they also offer a profit via something that is far more certain than the short-term direction of the markets, that really shows their worth. The ProShares UltraShort 20+ Year Treasury ETF fills this need.

One other thing to remember. There is always "erosion" to consider when buying inverse or leveraged ETFs or open- or closed-end mutual funds. As a result of daily marking to market and the small fees involved when entering a swap, such funds will decline minutely day by day.

This erosion factor is nothing but a minor annoyance to me. First, I believe rising rate pressure will build enough to ensure we only have to consider erosion for a relatively short time. Second, I have great faith in my national government to do whatever it takes to repay Treasury bonds with dollars worth less and less.

TBT, my Anti-Treasury, will rise as the value of 20-year Treasury bonds decline. When bond yields rise, prices decline. Simple math, smart move.

Disclaimer: I do not know your personal financial situation, so this is not "personalized" investment advice. I encourage you to do your own due diligence on issues I discuss to see if they ...

more