How Bible Sales And Chipotle Explain The Economy

Image Source: Pexels

Today is my 22nd day (!) on the road for work this month - seven states so far, ten cities, eleven days to go. Every conversation starts with the economy. Interest rates, permits, expanding water and sewer infrastructure, AI initiatives, generational wealth transfers. In New York, I got into a cab to go speak at a conference. The driver asked where I was headed, I told him to go talk about the economy, and he said “Can you fix it for me?”

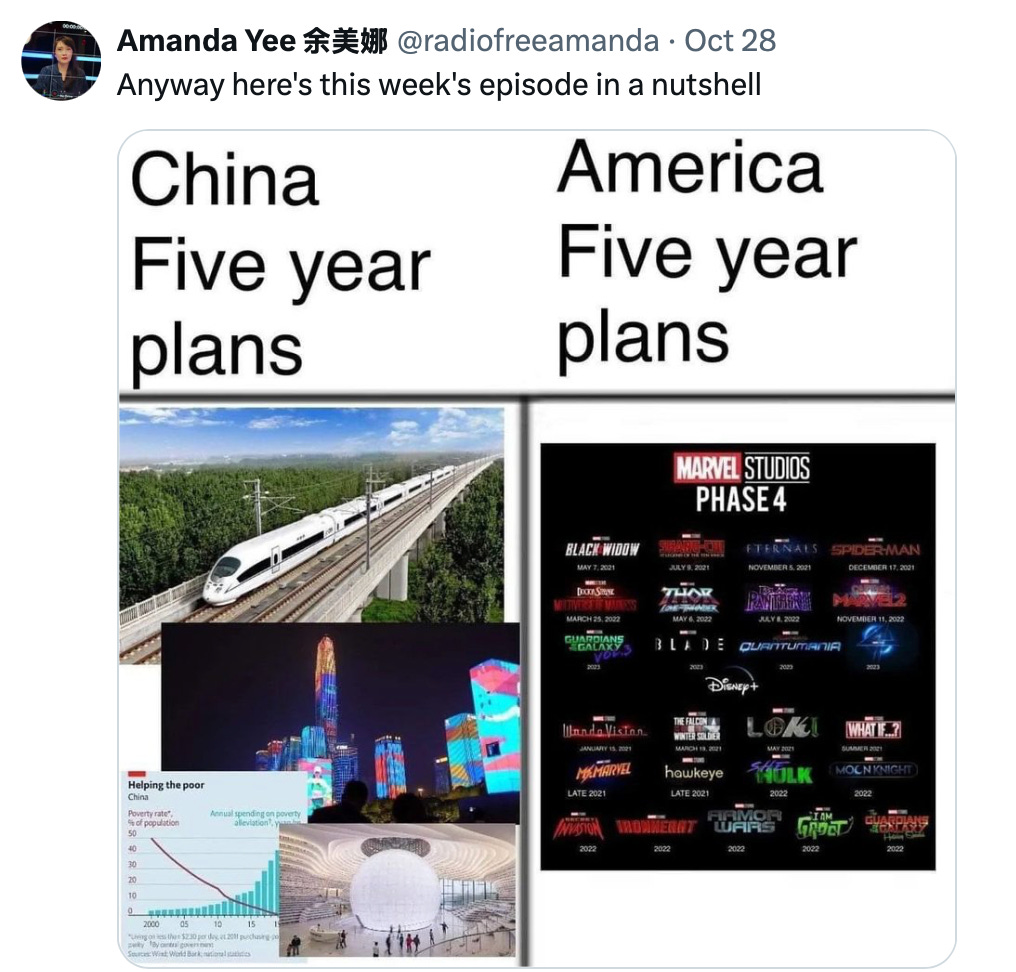

I wrote about the casino economy in the New York Times on Sunday, arguing that it has now infiltrated both private and public markets at unprecedented speed. It’s in the stock market, it’s in fiscal policy, it’s in the investments that venture capital firms are making, it’s in prediction markets - it’s everywhere. It’s nothing new1! But it’s accelerating.

And that’s why it sometimes feels like the economy isn’t “good” or “bad” anymore as much as it’s just… tradable? Half the country is barreling toward recession, 40 million people might lose access to food stamps because of the continued government shutdown, and meanwhile the stock market is acting like we’ve boarded onto a 24/7 all-access party cruise or something. Apparently, the invisible hand also deals cards.

Source: Mark Zandi

So - what’s going on beneath the party lights? What is the economy actually doing?

Monetary Policy

The Fed cut rates by 25bps again. The vote wasn't unanimous - Steve Miran, the most recent appointee, voted for a 50bps cut. Jeff Schmid voted for zero cuts. Everyone else settled on 25. It shows how strained managing the dual mandate has become.

Powell said tariffs were giving him a giant headache, which yeah. Imagine spending 4 years to get post-pandemic inflation down to 3% and then someone was like “wow… what if I just… undid all of that by enacting a tax on imports that companies would immediately pass along to the consumer…”

Powell also warned that another 25bps cut might not happen this year. The government shutdown means the Fed is flying blind - they don’t have the data they need. The shutdown has cost $18 billion so far (if anyone’s counting). Inflation isn’t totally fixed (2% is the goal, not 3%) but the labor market is increasingly wobbly, especially now thanks to sweeping job cuts that might be due to a correction from overhiring during the pandemic… or automation.

The market became immediately enraged when Powell said hey maybe not December, demanding that actually no, financial conditions should actually be even easier as Nvidia hit $5 trillion in market cap and as OpenAI, a company with $20b in revenue, potentially prepares for a $1 trillion IPO after shedding their nonprofit status in a way that feels questionably legal2. Even easier!

Monetary policy has become a mood ring - the Fed is trying to keep markets and consumers feeling confident, but the two groups need very different things. Some of it is structural.

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy is responsible for fixing the structural issues. As such, there seems to be no clear path out of the government shutdown? On November 1st, 40 million people could lose access to SNAP benefits3, ~60% of which are children and the elderly. It’s illegal for the government to withhold this money, since Congress pre-appropriated $3 billion to cover situations like this.4

The US is also paying troops (which is good and everyone in the government should get paid5) and just sent $40 billion to Argentina, but somehow can’t find money to feed retirees and kids, so this really feels like it’s about priorities, not constraints.

And while all this unfolds, President Trump also announced that the newly-titled Department of War would begin nuclear testing, which is a great way to plunge us into a Cold War with China. Nuclear brinkmanship is fiscal and industrial too, demanding resources that could crowd out the domestic repair that the US needs (and that which was promised).

As Jeffrey Lewis wrote in Foreign Affairs, America’s nuclear advantage exists because China and Russia stopped testing. If they start again (and they will, if we do), that edge disappears.

The US has two global advantages right now (to extend the metaphor, the only two chips America has left on the table): (1) Trust and (2) Technology.

-

Trust comes from the dollar, from the Federal Reserve being not politically manipulated to cut rates, from being a good trading partner etc. All of that is, you know, wildly unstable.

-

Technology comes mostly in the form of AI and weapons manufacturing (nuclear as mentioned above). The AI story parallels it. Nvidia (the $5 trillion company) is lobbying to sell its best chips to China. Everyone is like hey maybe don’t? The IFP has a great piece analyzing the consequences of selling the chips to China, and several analysts have already spoken out against the deal. The logic is “what if we, Nvidia, sold our really cool chips to China and therefore the technological edge of the US for one more trillion in valuation?” The topic didn’t come up directly in Trump and Xi’s trade deal conversation, but when there is a lobby, there is a way.

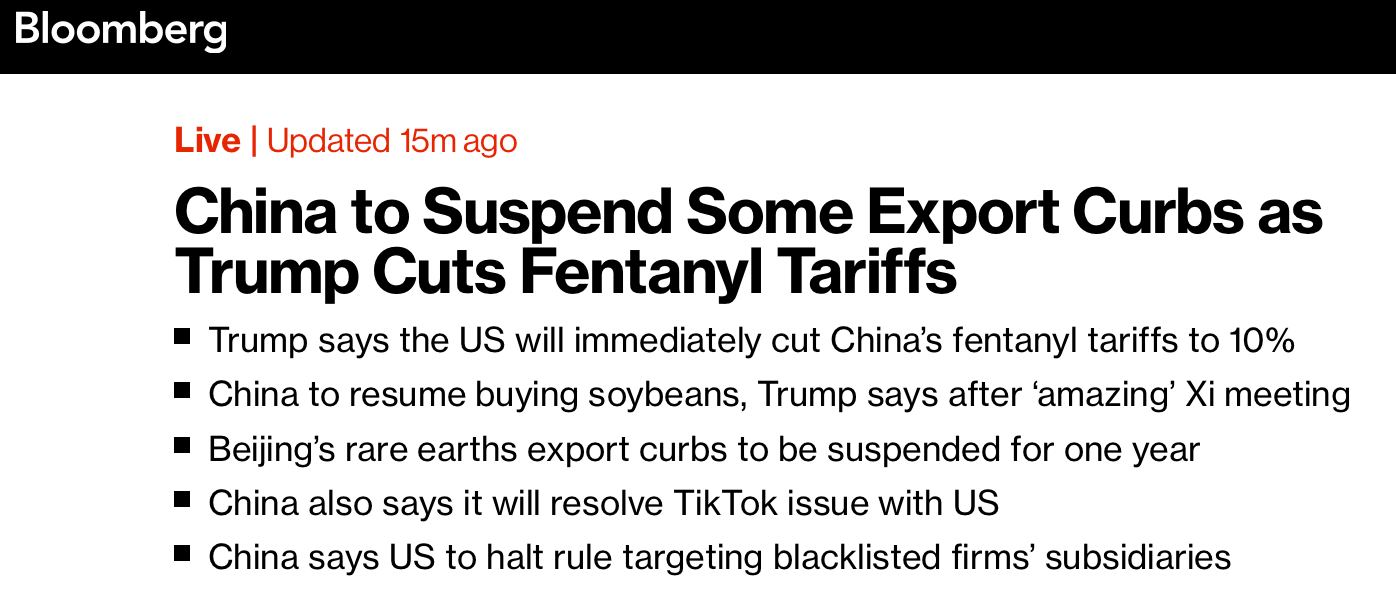

The trade conversation went well it seems. A TikTok deal is also in the works, which Xi has called ‘spiritual opium’. The tariffs on China have also been cut to 10%. It appears we have never left the month of April.

The Senate has also overturned Trump’s 50% tariffs on Brazil, which is cool because I totally forgot there was a third branch of government. All of the tariffs might be illegal, depending on the Supreme Court. This specific ruling still has to pass the House and then Trump himself, which won’t happen, but you know, it’s nice, to know that the Senate exists.

The K-Shaped Economy

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been on a lot of panels that are essentially like “Why Gen Z is Doing That”. I wrote a piece a few months ago about “Gen Z and the End of Predictable Progress” but it really should have been titled “Why The Economic Ladder Has Completely Changed For Everyone Due to Policy Choices”.

One driver of our changing economy is demographics. We talk about it in generational terms because that makes it easier, but it’s impacting everyone. The population is aging, and policy increasingly favors some of the elderly (don’t forget 43% of boomers have no retirement savings) over the young.

Across the country, states are slashing property taxes, which is the source of 70% of local revenue. Florida, which already has no income tax, wants to get rid of property taxes entirely. Illinois wants to exempt homeowners who’ve lived in their houses 30+ years. It’s unclear where replacement revenue to keep these economies going for our future would come from - or whether voters even care.

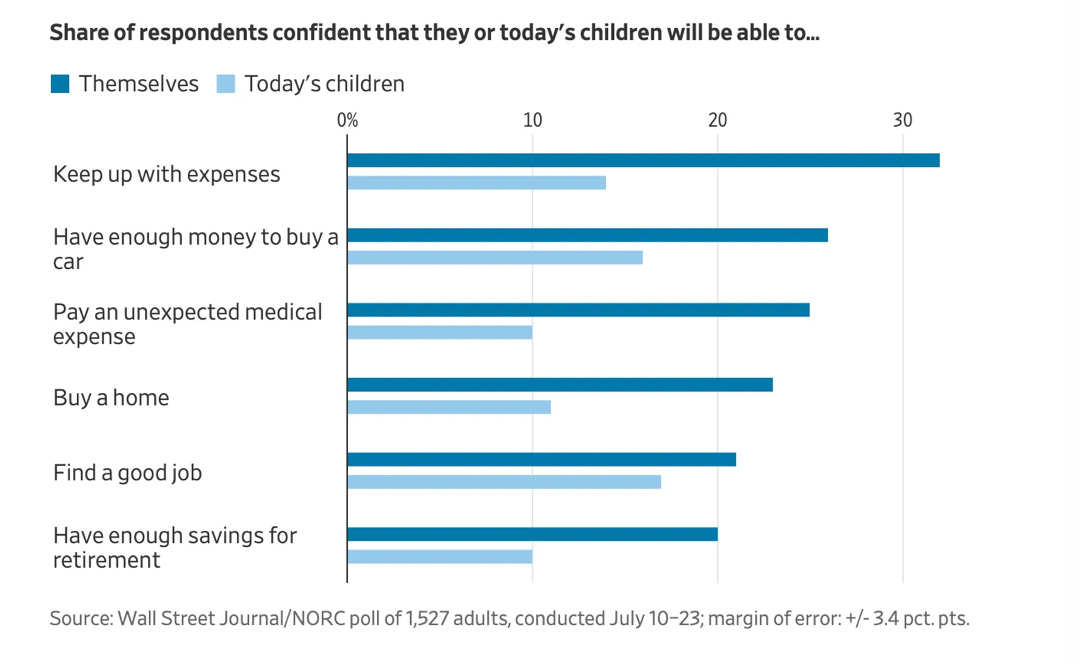

A lot of young people are very worried. The WSJ put it neatly: The Economy That’s Great for Parents, Lousy for Their Grown-Up Kids, highlighting how a generation that came of age during zero rates and rising asset prices is now facing a ladder that’s missing several rungs. Young people - and their parents - don’t believe that upward mobility will be there for them.

(Click on image to enlarge)

According to the New York Fed’s Labor Market for Recent College Graduates tracker, unemployment for new college graduates up 30% since the pandemic versus 18% for all workers - the highest level in a decade, outside of the pandemic unemployment spike.

And that’s part of the reason that people are turning to the stock market - over half of Americans who make below $80k a year have taxable investment accounts, with half of those investors entering the market within the last five years. People are trying to create their own financial foundation. Markets feel more stable than institutions.

And that ties into the financialization of everything. In industrial capitalism, firms existed to produce and expand. Carnegie and Ford (for all their flaws) understood the ecosystem: workers were also consumers, so paying them well was good business.

But now… we don’t seem to think of it that way. That’s a part of financialized capitalism.

-

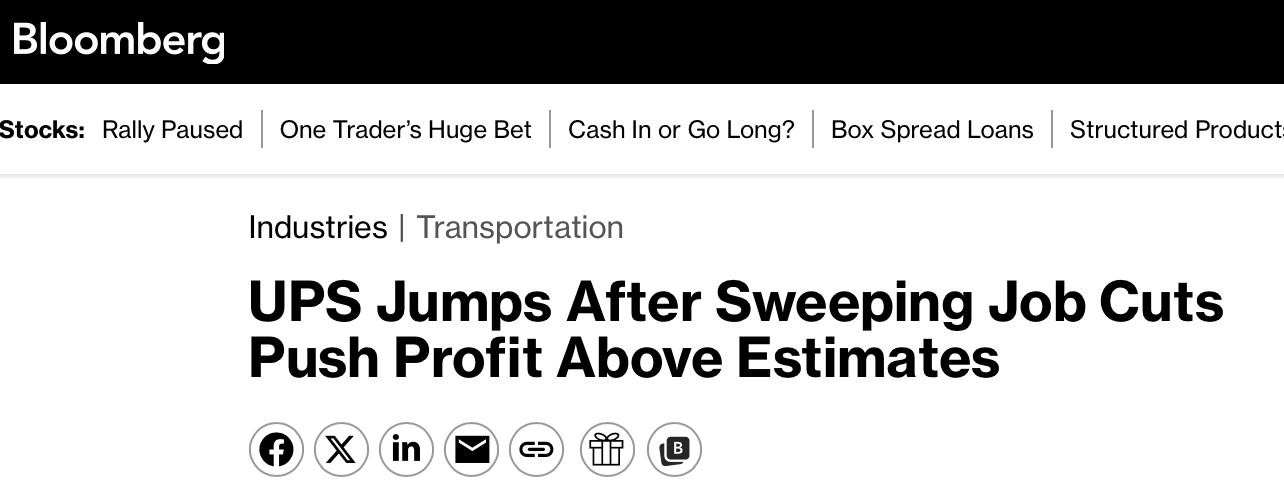

Now, companies grow by firing, not hiring. Now, it’s like, well what if we had a robot that’s actually operated remotely by a guy in Pacific Heights do everyone’s job.6 That would be cool, right?

-

UPS got a huge thumbs-up from the market for cutting 34,000 jobs (and outsourcing jobs to USPS?), a focus on efficiency instead of expansion. Why build or invent when you can just optimize?

-

It’s also a part of a broader inversion of values. In America, we now treat the jobs that keep the world running like teachers, sanitation workers, nurses, delivery drivers as failures of ambition, while the real prestige lies in moving capital or manufacturing hype.

Efficiency has replaced expansion as the primary growth narrative, which creates a feedback loop - fewer workers, weaker training, and less innovation.

It’s a form of the AI Becker problem, as detailed by Luis Garicano. Automation erases the “training ground” work that once created experts. When machines do the junior tasks, no one learns the senior ones. Apprenticeship collapses. CEOs, driven by short-term preservation, hype AI as salvation because it buys them another quarter.

Beyond AI-hype, Chipotle CMG had some interesting data in their earnings call, noting that people 25 to 35-years old have started dining out less. They cite “unemployment, increased student loan repayment, and slower real wage growth” as the primary headwinds. The whole call was essentially like “yeah, it’s not our burritos, it’s the economy”. Kraft Heinz KHC stated in their earnings call that “we now have one of the worst consumer sentiments we have seen in decades” (which might reflect GLP1s more than anything).

But it isn’t the burritos. We do have a K-shaped economy7 - the top keeps rising as the bottom falls. That means that the really wealthy (the top 10% driving 50% of spending, for example) are doing quite well. Their credit-card spending and travel budgets have surged alongside stock and home-equity gains (they are celebrating the new 100% tax write-off by buying private jets).

For everyone else, the economy has become something to believe in rather than participate in, a system that promises meaning through motion. That’s the real mood of the economy right now - everything is a trade. Money, work, meaning, even faith.

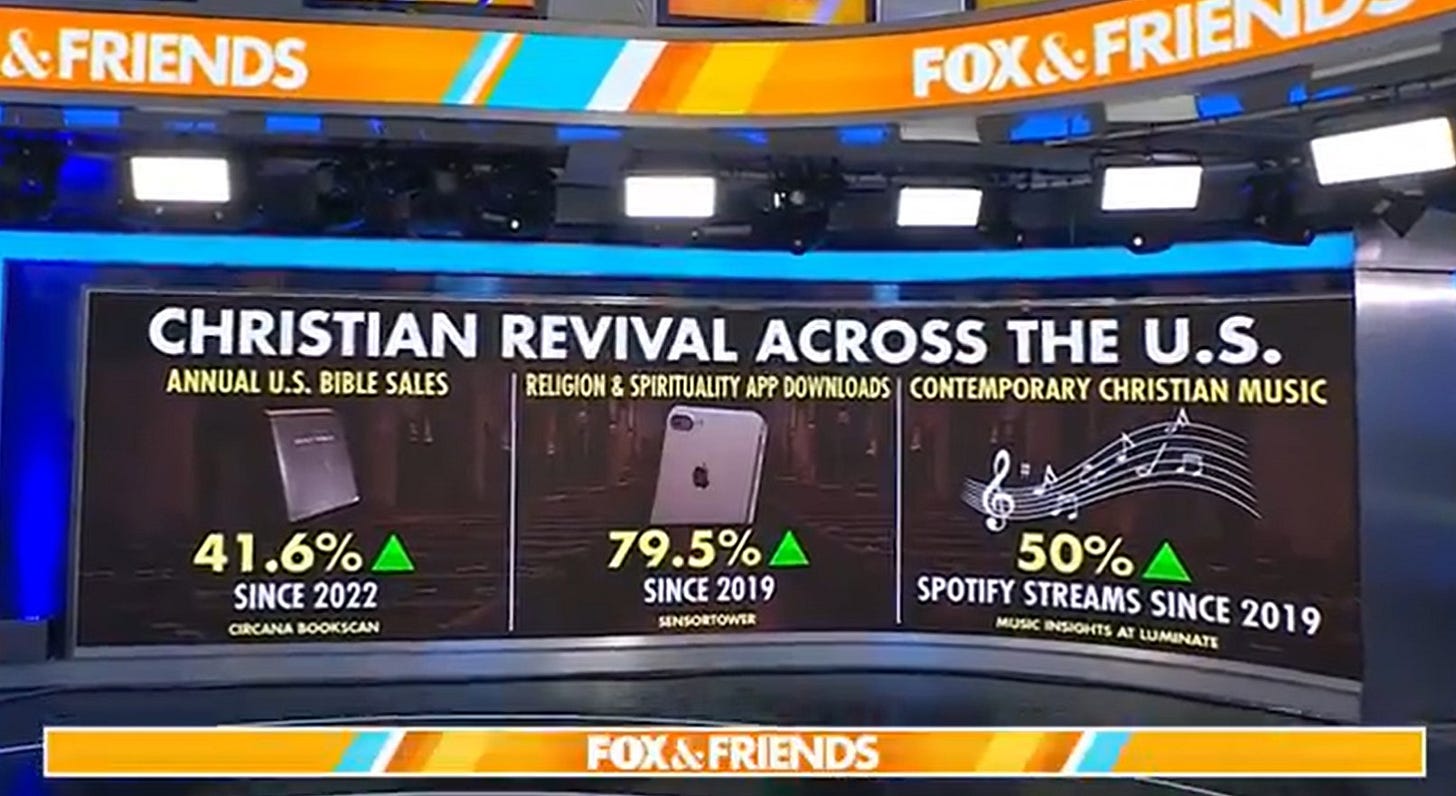

Bible sales are up roughly 40% since the pandemic, but church attendance is down to 30% from 42% two decades ago and 38% ten years ago. It’s aesthetic in a way - aesthetic spirituality, aesthetic politics, Baudrillard and Debord would have a blast.

When belief itself becomes transactional, risk stops feeling like a financial concept and starts feeling like a moral one. People don’t just gamble with money anymore; they gamble with time, attention, identity - anything that might yield security or a sense of control. The markets are only the macro version of that instinct.

That’s why the economy feels both booming and brittle at once: we have extraordinary wealth concentration coupled with mass participation in markets. Wealthy households and large firms transfer risk through diversification, hedging, political insulation (like donating to a ballroom maybe). Everyone else absorbs risk through gig work, debt, market exposure, and health costs. It is the logical outcome of labor precarity + 401(k)ification + income volatility. Risk always rolls downhill, but lately it looks like belief too.

The fixes for some of this aren’t complicated (it’s ideas that many have been talking about for a long time). Create portable benefit pools that follow workers between gigs. Build a public infrastructure corps that provides an employment floor. We have examples as to what works, like Singapore’s sovereign wealth model, Germany’s apprenticeship programs, and Denmark’s flexicurity system.

The goal is probably to not ban the casino but rather to build something slower beside it. Every speculative boom eventually exhausts its own attention span. Markets will always trade. The invisible hand will keep dealing. The work is to make sure the table doesn’t collapse.

1. A lot of people thought that I thought it was something new, which I sure don’t

2. They are still being sued for ‘defrauding investors’ about its commitment to a charitable mission. I guess a $1 trillion IPO can muddy that.

3. Walmart takes 25% of all SNAP dollars

4. Isaiah 58:7 and Matthew 25:35 and Proverbs 14:31 if we want to get technical here

5. I do believe that Air Traffic Control should be privatized at this point

6. I actually think this company means well and is trying to create something that really can help people but Joanna Stern’s video on it… underscores how complicated it is

7. Peter Atwater has been talking about this concept for years and years - if you’re interested in more, definitely read him

More By This Author:

6 Economic Lessons From Books About Power, Propaganda, And Decline

AI That Works For Workers: Survey Results

How AI, Healthcare, And Labubu Became The American Economy

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, ...

more