Hard Or Soft?

Image Source: Pexels

A challenge in writing a weekly letter like this is that the economy never stops. Important data keeps accumulating, whether I write about it or not.

A lot happened in the last four weeks: an FOMC meeting with major policy changes, a surprising jobs report, important shifts in the bond market and yield curve, hurricanes, China, some geopolitical events, and a political race, just to start. I haven’t mentioned them because I was on other, also important topics. Now it’s catch-up time.

One popular narrative right now says the economy is slowly returning to normal following COVID disruptions and then a severe inflation wave. That’s not entirely a fantasy; many long-term trends do appear to be resuming their pre-2020 paths. But it depends heavily on how you define “normal.” Some things change, others don’t. Normality is always a moving target.

Many analysts expect a recession by next year. Then again, those who have been forecasting the US economy to continue on its growth path have been right for some time. With the stock market making all-time highs this week, it does look more than merely Muddle Through.

The real distinction is between the economy we have today vs. the hypothetical, unknowable economy we would have if that virus had stayed where it came from and Russia hadn’t invaded Ukraine. Today’s economy would probably look different. But that’s pure guesswork.

Can we still rely on rules forged in a world that no longer exists? Maybe. I’m more in the camp that we cannot—at least not without extraordinary caution. I believe with the government deficit and debt growing massively and the Fed’s aggressive policies, we have crossed a Rubicon, an “event horizon” where basing predictions on past data relationships is far more difficult. But since past data is all we have, forecasters still use it.

We do know one thing, however. The effects of 2020–2023—the pandemic, the Fed, the inflation, everything else—grow more distant with each passing day. The runway metaphor is overused but it fits: Planes can’t stay in the air forever. This one will land. The question is whether we passengers will feel a hard or soft landing.

Let’s Not Forget Helene

The headlines in the media this morning are all about Hurricane Milton. I have so many friends I’m communicating with in Florida. It is a big deal. But I also have friends (and I assume readers) in Western North Carolina where the situation is even more dire. The death toll is already in the hundreds and will certainly grow. Locals tell me it could be well over a thousand. Infrastructure in many mountain communities will be down for months, if there is a community left. Whole towns have been wiped out. Talking to locals, it doesn’t sound like there was much of an evacuation effort, as unlike Florida, they had no experience with hurricanes.

I have a longtime friend, Tricia Zehr, who moved from California to Western North Carolina years ago. She has been my eyes and ears into the situation there.

It turns out there is a small church in the area called Anchor Baptist Church that has been doing relief work for over 35 years (since Hugo) for disasters all throughout the South. They have a professional staff with warehouses and facilities and a volunteer network plus a network of hundreds of churches they worked with in other disaster situations. Now, sadly, the disaster has come to their local area. Those churches they once helped are now reciprocating with supplies and volunteers.

Food for thousands of families is literally a problem. The church has become a central source for people to drop off supplies (near the local private airport) but is also then sending those supplies on to other churches throughout the area where local pastors and volunteers know the people in their local communities. They are connecting with these pastors and churches and sometimes flying them in with helicopters to find out who needs help when roads are not passable. They’re working with the local police and fire departments in the small towns to give them what they need, often with volunteer helicopters and planes, as the roads if they still exist are blocked. There are volunteers who literally use mules or horses to get to people back in the mountains. They coordinate volunteers to cut trees and clear housing and roads. I can’t even begin to describe the phone conversations about the amount of work they are doing.

They are going to be supplying food for months going into the winter, when tens of thousands of people will still be without homes. The Appalachians can get cold, and it is mid-October.

I could spend an entire letter writing about this, but let me ask my generous readers to make a donation to Anchor Baptist Relief. You can see some of the work they do here. 100% of your donations will go to relief supplies and food.

New Direction

Back to the more mundane. The Federal Reserve started raising rates (way behind the curve) in March 2022 and stopped in July 2023. Then began the giant guessing game of when they would reduce rates. The answer turned out to be September 2024. We can debate whether the Fed waited too long or not long enough, but here we are.

While every cycle is different, this one seems particularly so. We are not following the “standard” sequence, which goes like this:

- An overheated economy makes demand outstrip supply, causing price inflation.

- Central banks tighten policy, discouraging credit-financed activity.

- Employers reduce payrolls, leaving workers with less spending power.

- Producers have to cut prices to maintain sales, ending the inflation.

- Another growth phase begins and the cycle repeats.

In this case, the price inflation that began in 2021 wasn’t growth-induced. It was more about supply disruptions, though fiscal and monetary policy did spark some unwise speculation. Then a war caused Europe to reduce its dependence on Russian energy supplies, with global spillover effects.

Central bankers have few ways to solve those kinds of problems, but they had to “do something” about inflation. Higher rates didn’t slow consumer demand or raise unemployment, at least not initially and not much even now. GDP kept rising, rolling merrily along and surprisingly higher. The inflation rate came down in most categories, housing being the prime exception. Wages rose, even adjusting for inflation.

That sounds a lot like the “soft landing” most of us thought unlikely… but it’s not over yet. Much depends on how the economy responds to the new direction in interest rates. Here, we must talk about which rates are going in which directions.

Here’s the question: Who is going to be helped by modestly lower short-term rates? What activity are they going to stimulate that isn’t already happening? And who will be hurt?

The Fed’s power is mostly over short-term rates, primarily the overnight federal funds rate. The last year or so has been wonderful for savers, i.e., retirees or anyone holding a lot of cash. They’ve enjoyed nice, (almost) risk-free returns on money market funds, Treasury bills, etc.

Meanwhile, millions of homeowners who locked in low, fixed mortgage rates during the pandemic also have more spending power. This probably helped consumer confidence.

I suspect the Fed thinks its rate cuts at the short end would be accompanied by similar but slower declines at the long end, eventually restoring the yield curve to its normal shape. This would also bring down mortgage rates and reduce housing costs. If that was the theory, it’s not happening yet. Long-term Treasury and mortgage rates are actually up since the Fed began cutting.

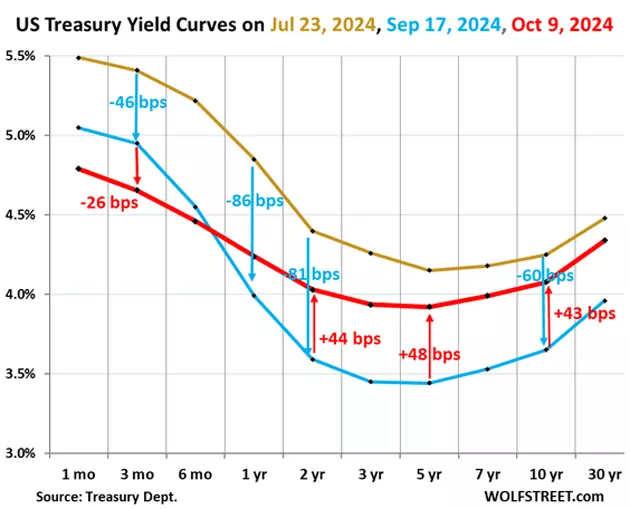

Consider this chart from the invaluable Wolf Richter.

The blue line is the yield curve on the day before the Fed’s cut. Notice how it compares to the red line 3+ weeks later. Rates at the short end fell, as expected. But debt maturities of a year and longer actually rose. Rates on the 10-year bond actually have risen 43 basis points. The difference is even greater since July (the gold line).

Mortgage rates (not shown here) generally take their cue from the 10-year Treasury yield, and indeed they rose, too. My friend Barry Habib of MBS Highway noted this isn’t unusual (even if it seems to be a surprise to some business media). Here’s Barry:

“This is not an unusual phenomenon—We have seen this happen in almost every rate cutting cycle except for 2019, and a lot of the reason why is investor psychology. Investors believe we have a greater chance of avoiding recession once the Fed starts cutting, which causes them to invest in the stock market at the expense of bonds. And the Fed cutting causes some to fear inflation rising once again, which causes bonds to temporarily sell off.

“But the Fed is cutting for a reason, and it’s because they are seeing the economy slow. And that helps the bond market and inflation come down. In each of the last instances where yields initially rose, they eventually fell much lower and we don’t believe this time will be any different.”

We will have to wait and see if Barry is right. I’m sure Jerome Powell hopes so; the Fed’s job will be a lot harder if long-term rates stay at these levels or rise further. It won’t be great for the federal debt problem, either.

Recession Brewing?

Speaking of the yield curve, we need to keep another historical pattern in mind. An inverted yield curve has long been one of the best recession indicators. In this case, the inversion happened in the summer of 2022. Why no recession yet? The indicator has been reliable but usually early. But two-plus years?

More By This Author:

Late Summer Sandpile

The Revolt Of The Public

The Time Has Come