The Time Has Come

I remember traveling as a young boy on long trips and asking my parents, “Are we there yet?” I was later punished for this annoying behavior by having my own children ask me the same question over and over.

On a national scale, we have been asking the same of the Fed. Now I think we can confidently say, “We’re here.” Barring unusual events, the Federal Reserve will finally start loosening its grip this month. Jerome Powell himself, speaking at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference, all but promised rate cuts are imminent.

Powell’s iconic line, “The time has come for policy to adjust,” grabbed all the headlines but his speech had other interesting points. It was also admirably free of the Fed doublespeak that often leaves us even more confused. Powell seemed to relish the chance to finally deliver what he feels is good news.

He wasn’t wrong. Inflation, while still too high, is much improved. Unemployment is up almost 1 percentage point from last year’s low, but still lowish. The Fed has room to lighten up a bit. Yet it won’t change our path toward a severe debt crisis in the next few years. One problem may be passing but a much greater one lies ahead.

To me, the most interesting part of Powell’s speech was his review of this inflation cycle’s origin and the Fed’s response. Some of it has a “victory lap” feel I’m not sure is justified. It’s still an interesting glimpse into his thinking and, I suspect, his desire to shape how history will record this period. Today we’ll review Powell’s address and compare it to what else is happening in Washington.

First, let me thank David Bahnsen for jumping in while I was away fishing last week. His thoughts on Your Portfolio and the Election further highlighted how a debt crisis is all but locked in, no matter how the election turns out or what the Federal Reserve does.

Whose Confidence?

I’ve given Jerome Powell a lot of grief, along with a few plaudits. Ditto for all past Fed chairs. So, at the risk of surprising longtime readers, I recommend his Jackson Hole speech even if it is somewhat revisionist. This is his core thinking and will reflect what he does over the next 17 months of his tenure. You may want to read the transcript first and then come back here to read my comments.

Keep in mind, Powell and his staff knew this speech was critical. You can bet they debated every word. Powell thought carefully about what to say and how to say it, then said exactly what he meant to say. Some of it may be wrong but it’s not accidental.

He began by talking about the near-term economic outlook.

“Inflation is now much closer to our objective, with prices having risen 2.5 percent over the past 12 months. After a pause earlier this year, progress toward our 2 percent objective has resumed. My confidence has grown that inflation is on a sustainable path back to 2 percent.”

Note the pronoun change from “our objective” to “my confidence” on inflation falling toward that objective. Why say it that way? Maybe he knows other policymakers don’t share his confidence.

As noted, Powell’s “the time has come” line got most of the press coverage, but the following sentence got less attention.

“The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.”

I think this is a subtle but important shift. The FOMC members have gone from “We haven’t decided what to do” to “We’ve decided what to do unless something changes.” They’re on track to loosen but still arguing over details.

Note also how Powell mentions “the timing and pace” of rate cuts. That signals the possibility that whenever rate cuts start, they could happen in something other than 25-basis-point steps. (More on when they move to possibly cut more below.)

Finally, one more small but telling note in the way Powell describes current policy.

“We have held our policy rate at its current restrictive level since July 2023.”

It is true that the federal funds rate has been at its current level since July 2023. But Powell goes further, characterizing it as a restrictive level.

Not So Transitory

Powell spent most of his brief Jackson Hole appearance reviewing the latest inflation cycle. In his telling, the Fed had little to do with inflation’s rise and a lot to do with its fall.

Talking about the Fed’s aggressive COVID response, Powell said:

“At the Fed, we used our powers to an unprecedented extent to stabilize the financial system and help stave off an economic depression.”

I haven’t checked, but I’m pretty sure sitting Fed chairs don’t often use the word “depression” in the sense he did. Powell says depression wasn’t just possible but imminent in early 2020, and that the Fed’s actions helped prevent it. That last part is debatable, but the important part here is that Powell not only believes it but has no regrets. He went on:

“After a historically deep but brief recession, in mid-2020 the economy began to grow again. As the risks of a severe, extended downturn receded, and as the economy reopened, we faced the risk of replaying the painfully slow recovery that followed the Global Financial Crisis.”

If the risk of repeating that “painfully slow recovery” was foremost in their minds, it makes the Fed’s policymakers look like generals fighting the last war. In fact, COVID was not at all like the Great Financial Crisis. It was a different animal that needed a different approach.

One sign of this should have been that, unlike the post-GFC period, this era quickly turned inflationary. Powell described its appearance.

“After running below target through 2020, inflation spiked in March and April 2021. The initial burst of inflation was concentrated rather than broad based, with extremely large price increases for goods in short supply, such as motor vehicles. My colleagues and I judged at the outset that these pandemic-related factors would not be persistent and, thus, that the sudden rise in inflation was likely to pass through fairly quickly without the need for a monetary policy response—in short, that the inflation would be transitory.”

Oops. But in Powell’s version of events, the Fed wasn’t fooled for long.

“For a time, the data were consistent with the transitory hypothesis. Monthly readings for core inflation declined every month from April to September 2021, although progress came slower than expected. The case began to weaken around midyear, as was reflected in our communications.

“Beginning in October, the data turned hard against the transitory hypothesis. Inflation rose and broadened out from goods into services. It became clear that the high inflation was not transitory, and that it would require a strong policy response if inflation expectations were to remain well anchored. We recognized that and pivoted beginning in November. Financial conditions began to tighten. After phasing out our asset purchases, we lifted off in March 2022.”

The data turned inflationary in October and the Fed pivoted in November. Really? That’s not my recollection. But this section may explain at least part of the delay. Powell seems to be saying the Fed had to stop its asset purchases before it could raise rates. He doesn’t explain why they needed six more months to do so.

Nevertheless, Powell says it all ended well. Having skillfully navigated the inflation cycle, “the time has come” to let off the brake. And that’s what they will likely do this month. Then what?

This speech was clearly a “victory lap” but the actual history is rather revisionist. They waited too long to raise rates and let inflation get out of hand, as I and others were writing at the time. Yes, much of that inflation was due to fiscal incontinence, but the Fed didn’t help.

Powell also didn’t mention how the Fed isn’t the only player. Something curious is happening just a few blocks away.

Opposing Forces

Last week we sent Over My Shoulder members a note on something few have noticed. The Fed may be poised to loosen short-term rates, but the Treasury is doing the opposite. Possibly because it has little choice as the debt continues rising. Let me explain.

Borrowing as efficiently as possible is important when you are the world’s largest debtor. The Treasury has a lot of discretion on how it manages the federal debt. It needs to raise certain amounts but can borrow short-term, long-term, or anywhere in between. Treasury can also repurchase its own debt, replacing that amount with newly issued securities at a different maturity. All this activity becomes more important as the amount of debt increases, as it has been and will continue to do.

Two important things are happening right now. First, the Treasury has been shifting a larger part of its new issuance to short-term Treasury bills. That’s a bit odd since the yield curve is still inverted, although the 2–10 spread is now flat. (That’s what happens when the yield curve starts normalizing. Typically, this is followed by a recession.) They are borrowing mostly in the zone with the highest rates. But there’s a reason for it, which I’ll get to in a minute.

The other new development is the Treasury has been buying back longer-term Treasury securities. This seems to have started in April and is an ongoing effort. For example, Wolf Richter reported last month they had repurchased $2 billion in 20-year bonds that had been issued in 2020 at 1.25%.

Again, this seems odd, if not foolish. If your debt is at a historically low fixed rate, why give it up? We are unlikely to ever see such low rates again. To me this seems like an “own goal.”

The net effect of Treasury’s activity—borrowing more at the short end, injecting liquidity into the long end—is to push long-term interest rates lower. It’s a form of economic stimulus, which might be okay but could also add inflation pressure… just as the Fed thinks it has inflation on the run.

Shifting more debt to the short end means that debt will mature sooner, maybe letting the government refinance at lower long-term rates. That seems to be the bet, at least. We’ll see how it works out. But they are likely right. Lacy Hunt thinks that the Fed needs to cut about two points over the next year. The market seems to think that as well. But if Lacy is right, it also means the economy will soften more than we now think.

But the bigger point is we now have not just the Fed, but the Treasury working to push interest rates in a desired direction. And not necessarily the same direction, though we should hope they at least try to coordinate. Powell and Yellen have worked together before.

Paradox of Negative Savings

Lacy Hunt in his latest note for Hoisington pointed out that net national savings is now negative and has been for some time. Personal savings are still positive, but the massive fiscal deficit is draining the potential for growth from the economy. Here’s what he said in his recent letter:

“Amidst a widespread deterioration in the economic landscape, it is crucial to underscore the current detrimental roles of monetary and fiscal policy. The sharp deceleration in detrended real M2 money supply growth, a fundamental cause of aggregate economic fluctuations, is a stark reminder of the past. Prior to nine of the 10 recessions since the early 1950s through the start of the pandemic, monetary restraint has consistently reduced inflation, economic activity, and short- and long-term bond yields.

“The worsening fiscal policy condition, as measured by the existing status of negative net national saving (NNS), reinforces the contractionary influence of monetary restraint. The premise of J.M. Keynes, founder of the Keynesian school of economics, was that excessive saving is the cause of major economic downturns. When individuals do the right thing (i.e., save for future needs and contingencies) consumer spending is insufficient to prevent economic slumps, which Keynes called the "paradox of thrift." Negative saving, however, means that Keynes' paradox no longer applies because no surplus exists. Thus, Keynes' solution of enormous deficit spending to drive the economy disappears. Indeed, it suggests just the opposite. Deficit spending must be reversed or net national investment, a requirement for future growth, will not exist.”

And there you have it. We are on the path to a no-growth economy which will make the deficits even worse. But if the deficit and the debt are causing the low growth, the standard “grow ourselves out of it” solution won’t work. Call it the Paradox of Negative Savings.

Payroll Conundrum

The ADP jobs August report came in at 99,000, well below the expected 161,000. The ISM reports we have been in a manufacturing recession for at least six months and lost 24,000 more manufacturing jobs last month. Higher income sectors like travel and hotels are busy. Auto sales are soft. Housing is getting softer as people are either balking at the high rates or waiting for lower rates in the future.

The BLS payroll number for August was 144,000, versus expectations of 160,000, and expect significant downward revisions (which I documented the reasons for a few weeks ago). June and July’s job gains were both revised down substantially, by a combined 86,000 jobs.

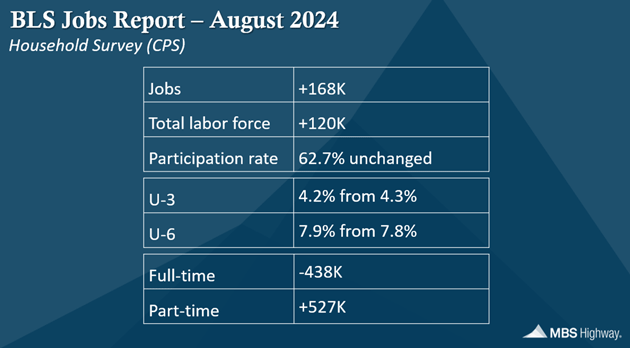

Headline unemployment was down 0.1% to 4.2%, but it was all part-time jobs, as we lost 438,000 full-time jobs. The household survey showed 168,000 jobs added, comprised of 369,000 from those aged 55 and over, offset by a fall of 383,000 for those aged under 25. Just ugh. The broader U-6 unemployment rate rose to 7.9% from 7.8%, the highest since October 2021.

From Barry Habib at MBS Highway:

Source: MBS Highway

Five of the last six rate cutting cycles began with 50-basis-point rate cuts. Powell and the FOMC can read this report any way they want, in terms of deciding whether to cut by 25 or 50 basis points. They are behind the curve, but the payroll data is not a screaming problem, but was still ugly. Powell in his speech left himself open for anything.

There is no clear direction from the futures market. It was 50–50 on Thursday and as I write is slightly favoring a 25-basis-point cut. That is offset by 100 bps of easing priced in by end of this year, and another 125 bps by the end of next year. Which gets us to Lacy’s suggested endpoint, if not as fast. If the economy weakens more, expect that rate cut cycle to accelerate. Let’s hope it doesn’t.

This is one more twist in what I believe will be a years-long run-up to the real crisis, when the bond market finally imposes some discipline on our free-spending ways. For now, I expect they can keep things reasonably stable, the Fed’s next move and election results notwithstanding.

By 2028? I think we’ll be in a darker phase. It could last awhile… but there will be light at the end of the debt tunnel.

Longevity Is Here

Over the next month, my publishing firm, Mauldin Economics, after lots of surveys and a great deal of thought, will launch two new initiatives. I want to introduce the first today. We are completely revamping our biotech information resources. A great deal of this will be focused on longevity and practical things that you can do to increase not just your lifespan but your healthspan. Chris Wood will be leading this effort with a new letter geared to help you.

Longtime readers can remember our old friend Patrick Cox. The depth of his research and knowledge on biotech is stunning. He went to work for Dr. Mike Roizen over the last four years doing primary work on all the information around various longevity research efforts. He has written over 100 different papers on a vast variety of topics around peer-reviewed research on what you can do to improve your own health and longevity, many of them simple and inexpensive (and others that are complex and expensive). He has become one of the premier “biohackers” in the world and is going to work with Chris.

We will make these available to you in the coming months and hopefully healthy years! There’s so much more but you can sign up here for the list of those interested in longevity and health. You really want to start from the beginning with us!

Dallas and Food for the Soul

I will be in Dallas Wednesday night for Thursday meetings with Mike Roizen and our team, flying back Friday. If you are practicing doctor in the Dallas area and have experience in multiple outpatient clinics and an interest in Longevity, drop me an email at business@2000wave.com and we will try to set up a meeting with Mike this Thursday. And yes, for those who are curious we will be making announcements in another 45 days or so. It will be exciting.

The weekend in the Haida Gwaii islands in far northwest British Columbia at a true 5-star fishing resort was simply over the top. Fabulous fishing with 29 of my readers. It was food for the soul. I really haven’t taken a lot of vacations lately, and I realized that I need more “time off” but even more I need face time and interaction with people. I used to get that with all my travel, but COVID changed that. Watching the 30 of us bond quickly gave me so much pleasure. Spending time in the boats having deep conversations was precisely what the doctor ordered. There was a general consensus that we will do it again next year. I will let you know.We are entering a time I think will include a deep crisis. We are going to need each other. We really do need to “find our tribe.” Watching my fellow fishermen and women convinced me that we need to do more to facilitate this. Stay tuned.

More By This Author:

Your Portfolio And The Election

Unemployment, Inflation And The Fed’s Choice

A Head Fake, Maybe