Energy Transition: The Challenge For Oil-Producing Countries

The Sixth Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, presents a stark environmental reality check. If this year’s record-breaking weather conditions are indicative, there is good reason for concern, particularly, where rapid developments in science and technology have enabled the attribution of specific global events to climate change.

Image Source: Unsplash

Carbon dioxide and methane gas emissions are major drivers of the current climate change process; oil and gas (55%) and coal (40%) account for the largest proportion of carbon dioxide emissions that are unrelated to land use, the group Global Carbon Atlas reports.

Countries as well as country groupings have been setting up climate change mitigation protocols. Accord de Paris for example, which was adopted in 2015 by more than 190 countries, set legally binding provisions for limiting global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2050.

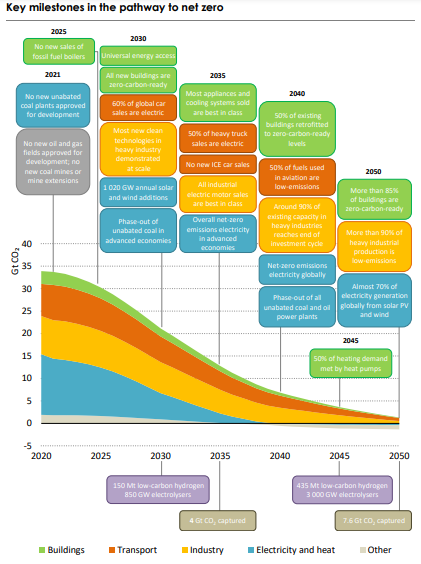

The International Energy Agency in its global energy roadmap for a net zero by 2050, finds that a precipitous decline in global crude oil demand from 90 million barrels per day (MMbpd) to 24 MMbpd would be necessary if that goal is to be met. And that would inevitably lead to a lot of “stranded assets”, assets on which significant financial resources have been expended to acquire, but which, for regulatory and economic factors, may have to be abandoned.

Analysts’ estimates of revenue losses to oil-producing countries in that scenario range from 65% to 80%, with most of them being countries reliant on oil and gas for quite significant proportions of their export revenues.

Structural Adjustment

Such oil-producing countries, particularly those that have not instituted adequate diversification and restructuring programs, would most likely face severe challenges as the global economy transits from fossil fuels to more environmentally-friendly energy forms.

Commodity prices are highly volatile, and countries that are very reliant on them for budgetary revenues would come under macroeconomic pressures when they fall. This is particularly true of oil.

Norway is a significant oil producer (1,712,937 barrels per day in 2020 according to Energy Information Administration, EIA), however, due to her diversified economy, oil and gas export proceeds make up only a comparatively small share of her total export. Oil and gas revenue accounts for an even smaller share of her fiscal revenue.

Nigeria is also a significant oil producer, churning out 1,775,940 barrels per day in 2020, according to EIA. For Nigeria however, oil and gas proceeds account for significant proportions of her total exports and fiscal revenue. When falling oil prices were compounded by the global pandemic in 2020, the country came under substantial economic pressure. The country’s budget for that year was based on an oil price of US$53 per barrel; oil prices plunged and for some time, prices for the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) grade fell below zero. The country has since become heavily leveraged, recording a debt service to revenue ratio of 98% between January and May 2021. Economic development under such terms would be difficult.

Countries with such high dependence on external revenue unwittingly prioritize the unsustainable collection and distribution of rent over enabling conditions necessary for economic viability. Many of such countries have for decades touted their economic diversification policies, but are at present, not any closer to that goal than they were then.

Market Fundamentals

There is little disagreement among most scientists on the reality of energy transition; the disagreement is in the rate of that transition. Indeed, different underlying assumptions in their analyses have given rise to different transition rates. That said, their estimates for the onset of peak oil demand, which range in the main, from 2025 to 2040, present real investment risks on both demand and supply sides.

On the demand side, that estimated peak in oil demand is being driven by the increasing rollout of electric vehicles (EVs) as well as regulations mandating increased engine efficiencies and other climate change mitigation provisions.

Global sales for EVs were up 160% in H1 2021, Canalys reports. The report shows that EVs accounted for 15% of all new cars sold in Europe over that period while for China, the value was 12%. Analysts expect those proportions to keep increasing.

Automobile manufacturing companies are also committing to phasing out Internal Combustion Engines (ICEs) in the near future. Both the VW and GM brands for example are planning to phase out ICEs by 2035. In addition, some EU countries are proposing a zero-emissions mandate by 2035.

In developing economies, particularly those with low per capita incomes, used cars imported from Europe or Asia are in the majority; very few cars are purchased brand new. With the planned phase-out of ICEs in Europe and Asia, the low purchasing power would make brand new, imported EVs beyond the reach of most; and inadequate operational infrastructure, such as battery charging portals, would make the use of such EVs impracticable.

On the supply side, there have been recent and massive additions to the global oil reserves. Following the frenzied growth of shale output in the United States, the Guyana Basin has in the past few years recorded discoveries of several billion barrels of oil; ExxonMobil (NYSE: XOM) and partners just recorded their twentieth discovery there.

Several other large discoveries have been recorded offshore Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Senegal in recent years.

The conjunction of falling demand and rising supply presents the real risk of “stranded assets” which has had a significant impact on oil and gas investment. Many oil majors are divesting “peripheral” assets to focus on core and sustainability assets. Even the very dynamic shale oil producers in the United States exercised operational caution instead of cashing in on the post-pandemic oil price rebound.

For countries that rely substantially on oil for revenue, the necessity for economic diversification is now even more acute.

Environment, Sustainability & Governance (ESG)

Many financial institutions and investors are currently reviewing their investment models. Some are completely exiting the fossil fuels business while others are predicting their involvement in business’ compliance with ESG protocols.

A group of 23 major insurers is ending its underwriting of coal-related businesses. While those insurers have been slow to exit the oil and gas sector, it is expected that mounting costs and alternative revenue streams would force that move. For example, the estimated damage from last month’s flooding in central Europe is about US$7.6 billion; and while premiums from ensuring oil and gas activities amounted to US$1.7 billion in 2018, that value was only 0.1% of those from property and casualty, Bloomberg reports.

Earlier, Axa announced restrictions on services to oil sands and Arctic drilling projects, just as Swiss Re intends to stop services to carbon-intensive producers by 2023.

The recent judgment against Royal Dutch Shell (RDS-A) by a district court in The Hague, on a case filed by environmental activists, will have wide-ranging implications for the oil and gas industry. The court found not sufficiently “concrete”, Shell’s declared policy of 20% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030, while aiming for net-zero by 2050. It ordered the group to reduce its global carbon emissions by 45% relative to 2019 by 2030.

The major's BP (BP) and TotalEnergies (NYSE: TTE) have already reconfigured their business models to reflect the energy transition, while a growing number of oil companies is following.

For National Oil Companies (NOCs), particularly in oil-dependent economies, the process of managed diversification is even more critical.

Saudi Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s NOC, is the world’s largest fully integrated oil company; in 2018 and 2019, its pre-tax income stood at US$212.7 billion and US$177.8 billion respectively (Saudi Aramco 2019 Annual Report). The oil price shocks of 2015 prompted the country to launch an economic diversification program, Vision 2030, to reduce its lopsided dependence on oil revenues. According to the International Monetary Fund, IMF, oil proceeds accounted for 85% of the country’s total exports while non-oil revenues accounted for 5% of her Gross Domestic Product, GDP, in 2015. However, by 2019, those diversification measures helped reduce oil revenues to 67% of the total, while increasing non-oil revenues to 8% of GDP (Oxford Institute For Energy Studies, January 2021). The country is aiming for a strategic balance between its oil resources and renewable energy.

For NNPC, Nigeria’s NOC however, the status is somewhat different. According to the company’s recently-released accounts, its liabilities exceeded assets by N4.6 trillion (US$10.7 billion) as of 31 December 2020; and that, compared to N4.4 trillion for 2019. The rise in liabilities is in spite of the company making a profit for the first time in its 44-year history. Its independent auditor, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) finds “a material uncertainty” which may cast "significant doubt on NNPC's ability to continue as a going concern".

The country’s Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), was recently signed into law. It is expected to bring transparency to the company’s operations, and its current governance regime deserves some credit, but the act’s provisions would have stood the country in better stead if it had come two decades earlier. That said, the adage, “better late than never” is probably apt.

Disclosure: None.

Really, the push for "greener" energy is a big portion of pricing energy beyond the reach of much of the undeveloped parts of the world, forcing floks to continue using far less healthy, more labor intensive, and more polluting sources of energy. In addition, expensive and unavailable energy results in continuing health problems and much shorter life spans for a whole lot of people.

Perhaps we should rather learn to live with a slightly warmer climate, such as the world had back in the previous temperature cycle. Consider that there must have been a lot of trees and jungle in the areas where all that coal is located underground. And it is rather obvious that trees do not grow in ice.

It needs to be understood that even if the emission of carbon dioxide were reduced to ZERO, that would not do anything at all to reduce the quantity already present.

Fortunately there is a system for removing it and releasing oxygen, which is green forests. Unfortunately, aggressive deforesting has been going on for quite a while. So the only "fix" is reforesting.

One more problem is that all the other sources of energy cost a lot more, and so by removing the less expensive source it is condeming the much less developed areas to reamain much less developed. Improved living requires energy for things like light and pumping clean water. BUT that is evidently not important to those who are removing cheper enery sources. What a shame!!