The Phlogiston Theory Of Stocks

Image Source: Pexels

Way back when… during the Holy Roman Empire (which is often described by history professors thusly: “it wasn’t holy, it wasn’t Roman, and it wasn’t an empire”) there was a man named J. J. Becher, and he was an alchemist and a physician. Now back in 1667, physicians thought bleeding was a great idea for addressing all kinds of diseases and maladies, so don’t be too hard on the mRNA folks if you’re Covid vaccine skeptical. Alchemists were looking for ways to turn lead into gold, and quite a few claimed they had accomplished that feat. Remember the “cold fusion” scam of the 1980s? If you consider the economic dimensions of it some theorized, it makes Elizabeth Holmes look like she was only selling Girl Scout cookies.

Becher came up with something entirely unique and it grabbed quite a few eyeballs. The phlogiston theory. The general idea of it was that “phlogisticated” substances contain this thing called phlogiston and that they “dephlogisticate” when burned, and that plants absorb this "stuff," which is why air does not spontaneously combust but plants burn very nicely. It also explains why the ashes left in the fireplace after burning a log or two don’t weigh what the logs did to begin with. The difference is the result of this dephlogistication and thus you have some semblance of a concept of a conservation of energy and matter, only it’s all theoretical and totally ignores the concept of oxygen being a necessary presence in the process known as combustion, or what combustion actually is, and its results, CO2 and water. But you know what they said back then if you put up a fuss hearing all this? Same thing they say today. “It’s science.” And in fact, this theory Becher professed did spark a focus on combustion that eventually led to the discovery of oxygen and great gains in scientific understanding. After all, “science,” then and now, is about observing and explaining, and trying to come up with a story about your observations and explanations that “adds up.”

Becher knew that something was happening when the action in the fireplace resulted in a disappearance of significant substance (weight of logs vs. weight of ashes) but nobody could explain where that substance disappeared to. But the phlogiston theory made it possible to offer such an explanation that “added up,” and that makes it science, like the irrefutability of 2 + 2 = 4. Whether it’s right is another matter; it’s science and it gives us something to hang our hat on. So science by this view is nothing more, or less, than a means to validate a question that needs to be addressed as noted by our observations, in the explanations with which we try to make sense of those observations.

You might say that a guy like Becher contemplating what happens when logs burn wasn’t a lot unlike a technical analyst looking at stock market machinations. Take, for example, the inverted head and shoulders. Why should a man standing on his head have anything to do with a bullish environment prospectively? Is that anything more reliable than the phlogiston theory was to people from 400 years ago unable to conceive that solids subjected to heat and combustion could become gases, lighter than air and that great masses of wood could escape through your chimney up into the atmosphere?

Similarly, who cares if the inverted head and shoulders makes rational sense? If you can correlate identifying that pattern with the prospective price action that is historically demonstrable, all you need to know is that you have an exploitable correlation with some degree of measurable probability. You don’t need to know why. Just like kids sitting in the stands at Yankee stadium. Their favorite batter comes up to the plate and strikes out. Why? Because one of those kids has his legs crossed or was picking his nose with his left index finger instead of his right. Is it scientific? Who cares? Or as Bill Clinton once said during his grand jury testimony on the Lewinsky affair, "It depends on what the meaning of the words 'is' is." What counts is that we see a phenomenon, we confirm that observation, we try to explain it and we try to find a means to show a correlation (not to be confused with a causality, which is of no concern anyway if the correlation is enough to make a buck with). Who cares if it’s science if it works and you can trade it? The rest is academic BS.

The resonant frequency

When as a little boy sitting at my mother’s spinet piano after school listening to the sounds that came out of it when I applied my fingers and thumbs to the keyboard as I’d seen my music teacher do, you might say I became the J.J. Becher of upstate New York in the early 1960s. Listening to the sounds from that piano enchanted me, and I imagine that was what Becher felt as he looked at the logs burning in the fireplace, and the cold ashes that weighed less than the logs. Where did the weight go? Similarly, I wondered what happens when I press the keys. It doesn’t take a little boy long to let his curiosity get the better of him, especially if mom is in the kitchen reading the latest from Book of the Month. Soon the lid of the piano was wide open and there I was watching as best I could see without a flashlight what was going on with the action and the hammers and the resulting tones. Wow! Who came up with this? I wondered as my eyes lit up and widened. I was already en route to my own phlogiston theory, even though I didn’t know it. And at that point in my life I’d never heard of either The Holy Roman Empire or J.J. Becher, nor did I have a clue about alchemy, the Medicis, or why a barber pole has red and white colors and what that means. But none of that stopped me. I was a “scientist” hurtling through space with inexorable momentum.

Now my Dad was a REAL scientist and he hated it when I did these things, but he also encouraged it, often without realizing he was doing so. He would come home with stuff he had either purchased or constructed himself to amuse and stimulate my curious mind. Returning from a business trip to the city, he brought me a clock he found at F.A.O. Schwarz (remember Tom Hanks and the “stompable” piano in “Big?”). And you could take this clock apart into about 50 pieces and put it back together, including a complete wind-up spring action with weights and pendulum and gears and cogs, thus learning how a clock works. One time he made me a simple little toy that was just a small wood pad with a small mast, and on that mast were two magnets with holes drilled in them to fit around the mast, and one magnet was floating above the other magnet because the like poles were aimed at one another. I took that one to school and put it on my desk and all my friends wanted to play with it. But when dad saw I had taken a hack saw to a piano string, or strewn around tools in his workshop, he was not so pleased with the monster he created. Fortunately, my mom stepped in to remind my dad that science marches on and not to get in the way.

My dad was a very good violinist, and the violin is a very difficult instrument to get the hang of. One day he was playing and our pet cat let out a mewl of major distress proportion. Not all cats do this but some do and it’s because catgut strings have a very personal impact on living creatures who share those components. You might say our cat was horrified feeling that inside her. “Hey, those are my ancestors, you butcher!” she might have been saying were she human. I could feel it in my heart.

A similar thing happens in less animated fashion when a violinist plays middle C and someone sitting at the piano holds down the sostenuto pedal. The middle C string on the piano will vibrate when subjected to the sound wave energy from the violin, doing through the air what the hammers do directly. That’s called a resonant frequency. This is when cats, violins and pianos, and humans are all on the same wavelength. As a little kid discovering this, it seemed like some kind of miracle, and I could feel it. Something bigger than us.

The RLH Volatility Model

The volatility model I started working on many years ago is based on all of these things in a kind of collective goulash sort of way. It is also dedicated to the principle I noted above that correlation is all that matters, if you can find it. If you find a correlation and it works, if it is reliable in its occurrence, that’s the goal. You are not trying to explain the mysteries of the universe, you are out to make a buck. Science is not a fixed concept, it is a platform for noting things, having observations and explaining observations. It is not sacrosanct. Yesterday’s scientific fact is today’s fodder for stand-up comics. One day Einstein’s work will look as foolish as Becher’s already does. But we will also still be able to appreciate the great things Einstein did just as we see what Becher’s work led to. This is how human beings make sense of their world and their lives. As E.B. White said, “there is no such thing as good writing, only good rewriting.”Scientists should say, “There is no such thing as good iteration, only good reiteration.”There is really no such thing as a scientist or a writer. I mean that in the sense of a writer can be a farmer, a doctor or a teacher, and all these things overlap and involve testing and mistakes.

Just like E.B. White wrote Charlotte’s Web, but he also wrote Elements of Style to teach us how to use the language. White cared enough about people to create a story for kids, making it credible that a shrewd spider had a heart big enough to save a pig from slaughter. Many mistakes, as well as progress, were made. Many kids learned compassion from Charlotte’s Web and the surprising places we find it.

What I saw in stocks was what they had in the financial pages of the newspaper. Just like you get in Yahoo Finance (YHOO) historical data. Date, open, high, low, close and volume. Reams of it. The Yahoo data go back to 1927 on the SPX. For years I have been staring at this data, absorbed. Did you ever see the movie Pi? That’s me.

You can operate on very small data arrays in myriad combinations and permutations. Remember, there is no such thing as good iteration, only good reiteration. You can move the parts around, tweak it, even take a hacksaw or a hammer to it. Remember, all that matters is correlations and reliable probabilities.

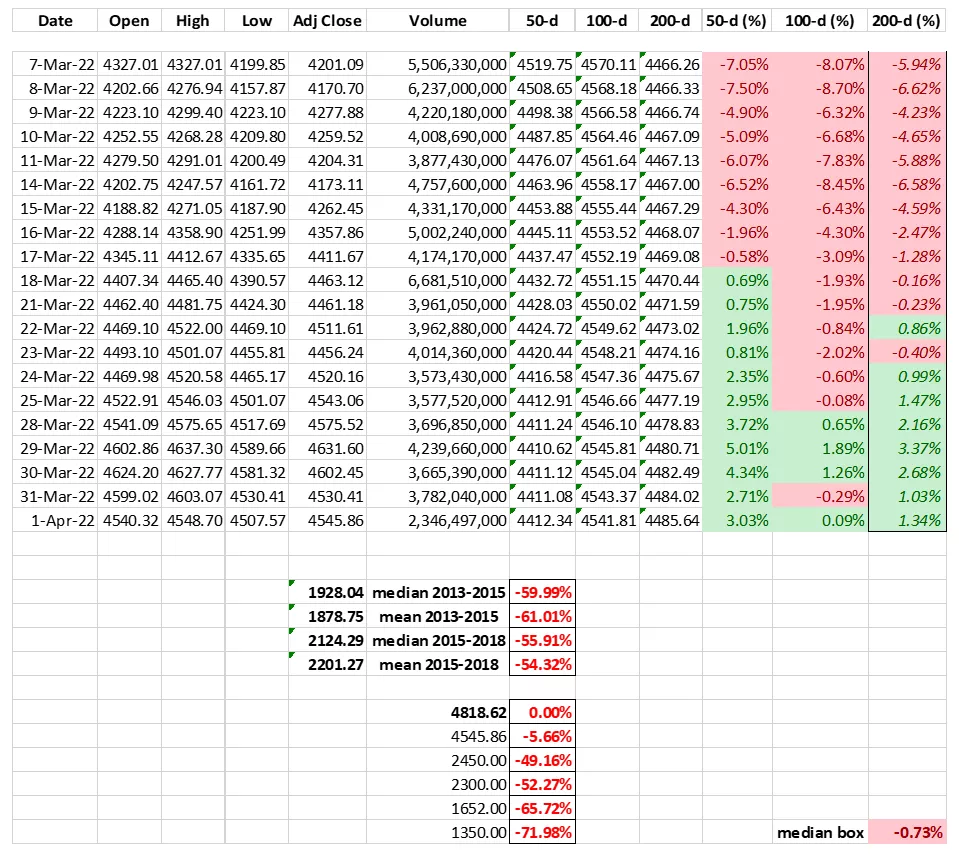

Here is a simple spreadsheet you can create with almost a century of SPX data (I am just showing the last few lines in it here):

(Click on image to enlarge)

There is nothing revelatory about what you are seeing above. Just data and a few simple operations. But you can play with this kind of stuff for hours on end and see what stocks do cycle after cycle. And you can invent your own operations.

Here are some examples:

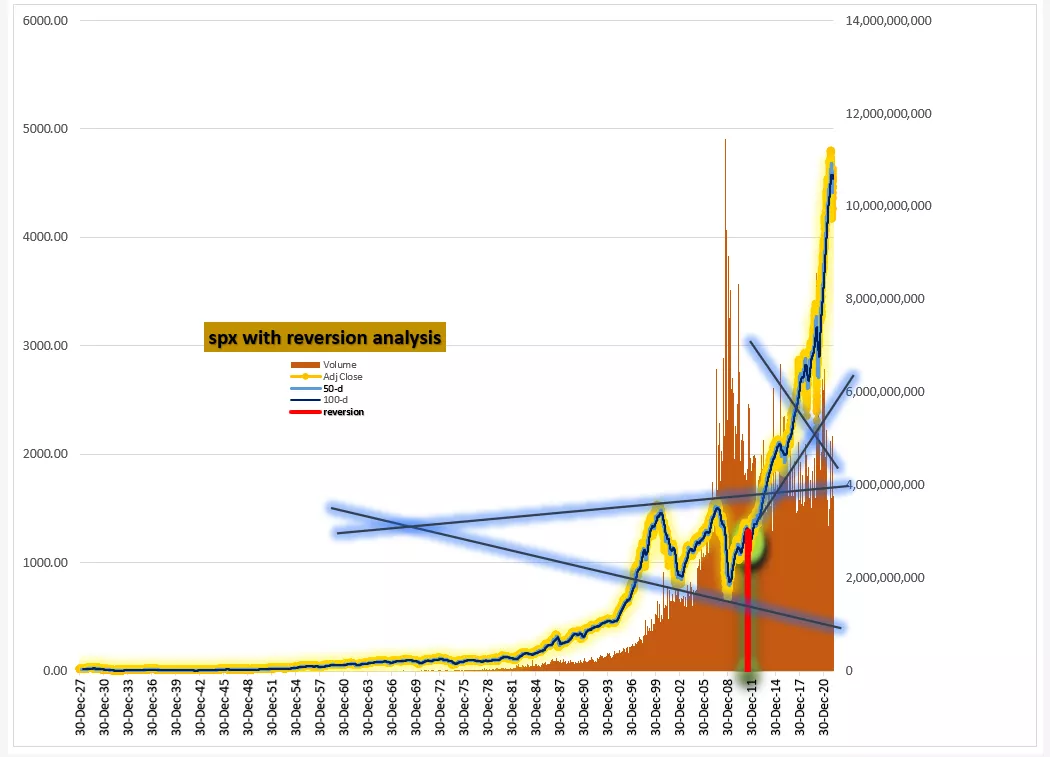

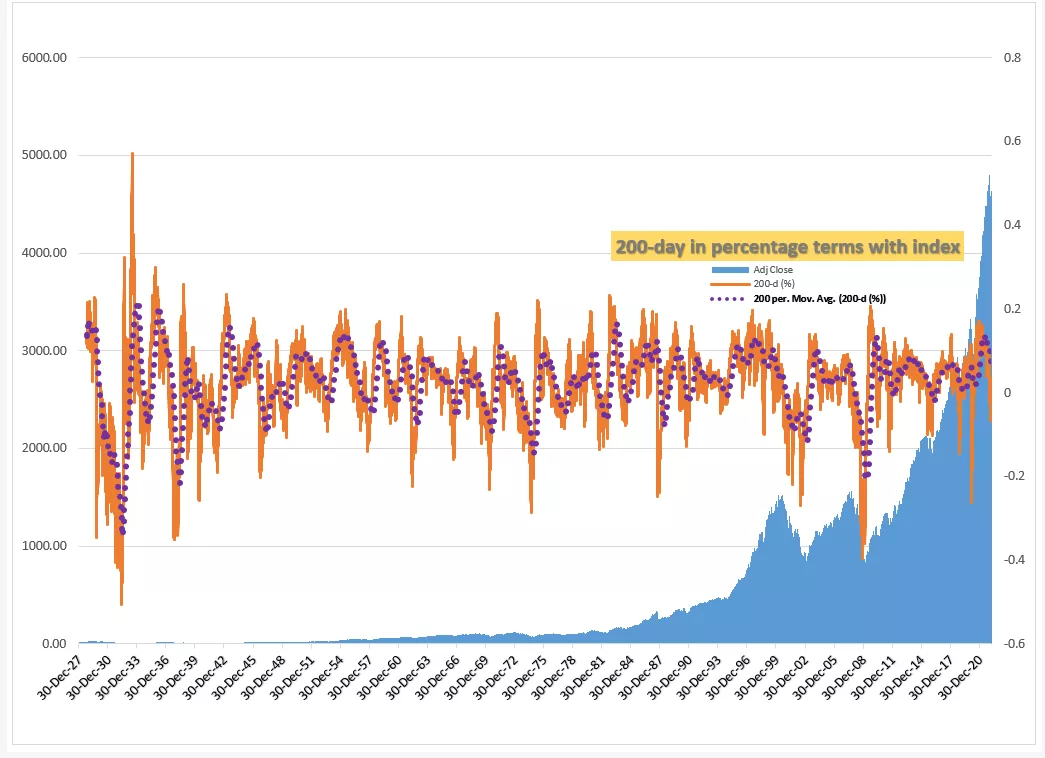

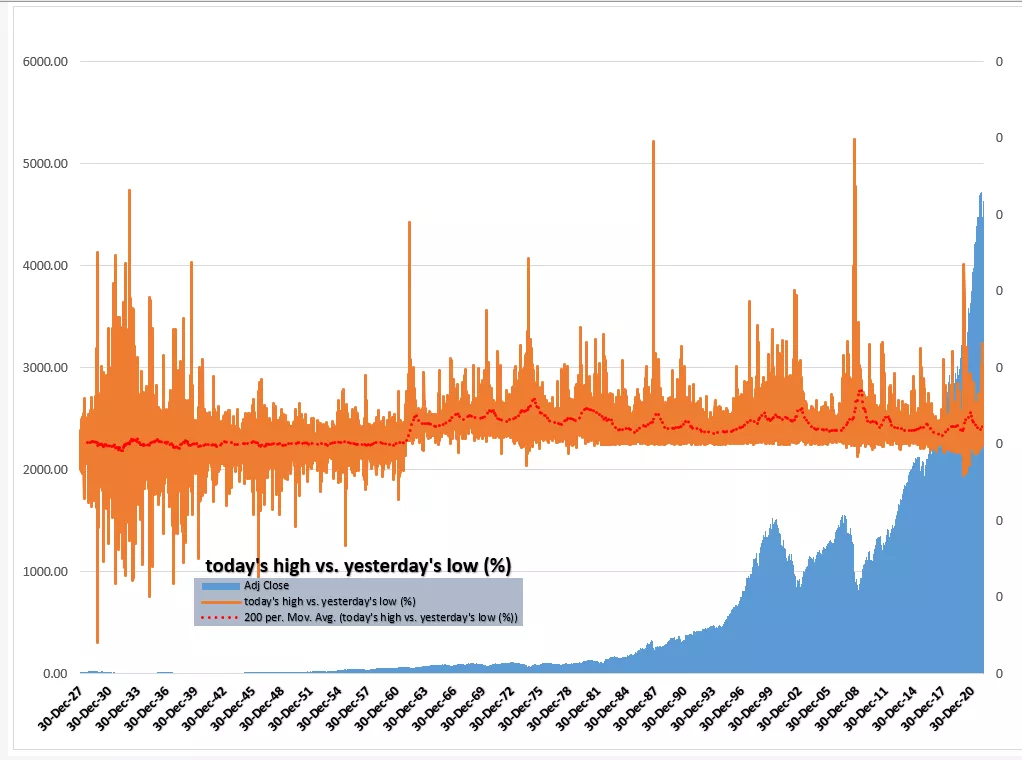

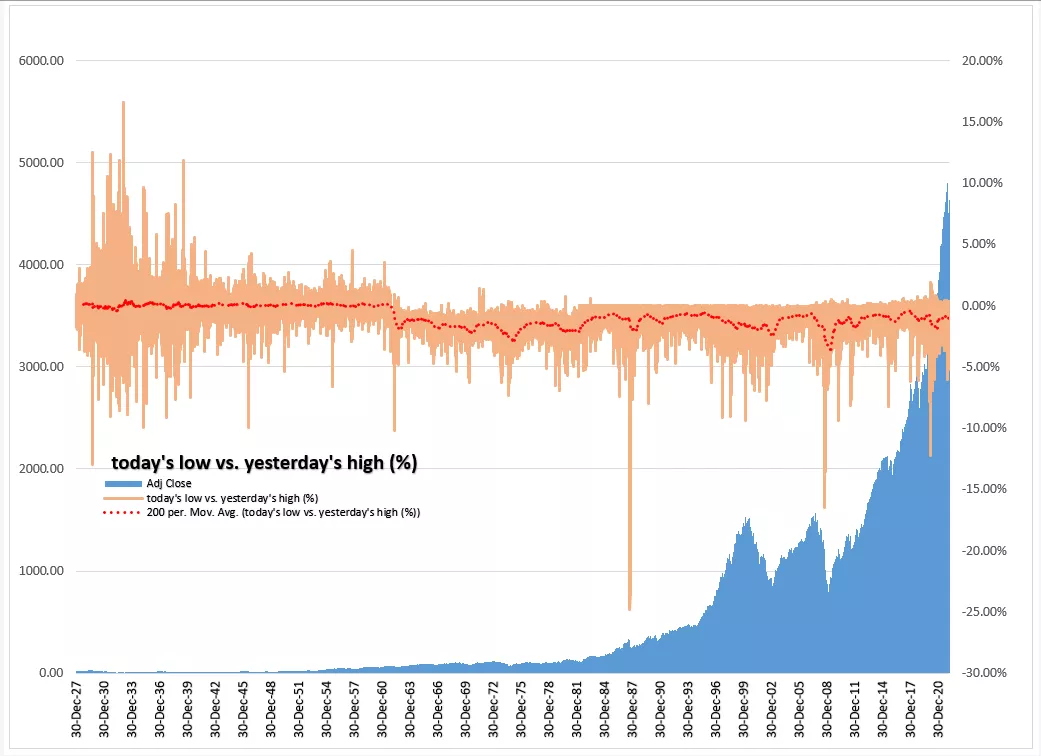

(Click on image to enlarge)

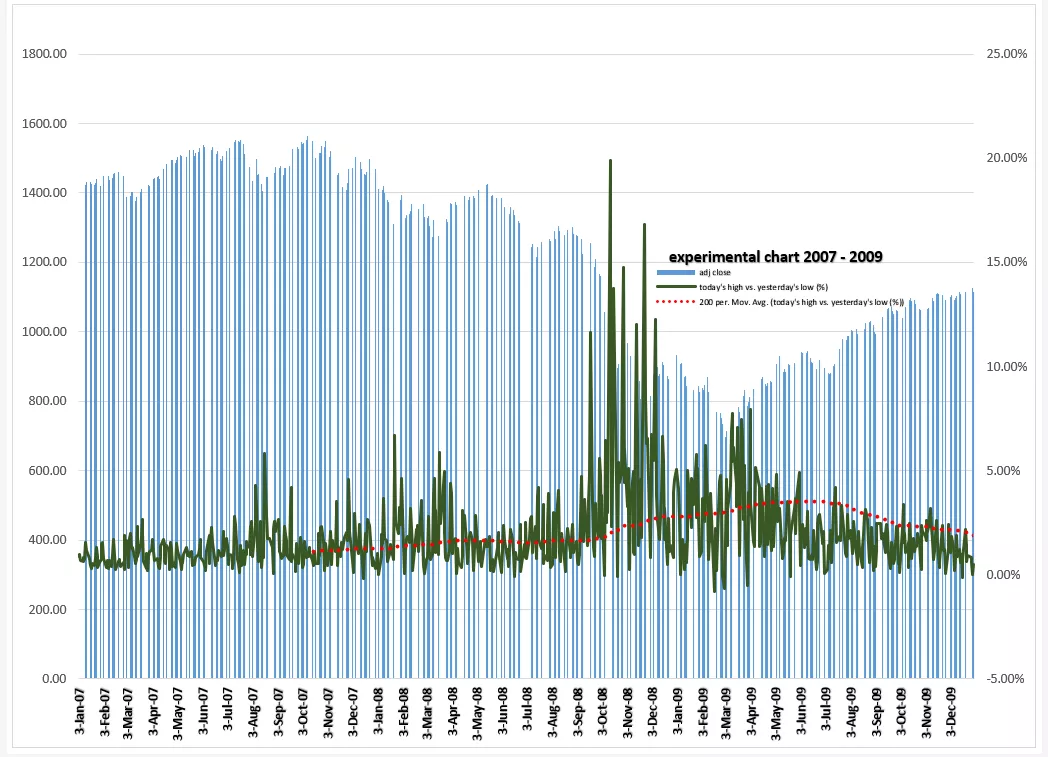

Once you have studied simple data like the above and put numbers to pictures, you will get additional ideas. The work above led to a knockoff data sheet that looks like this:

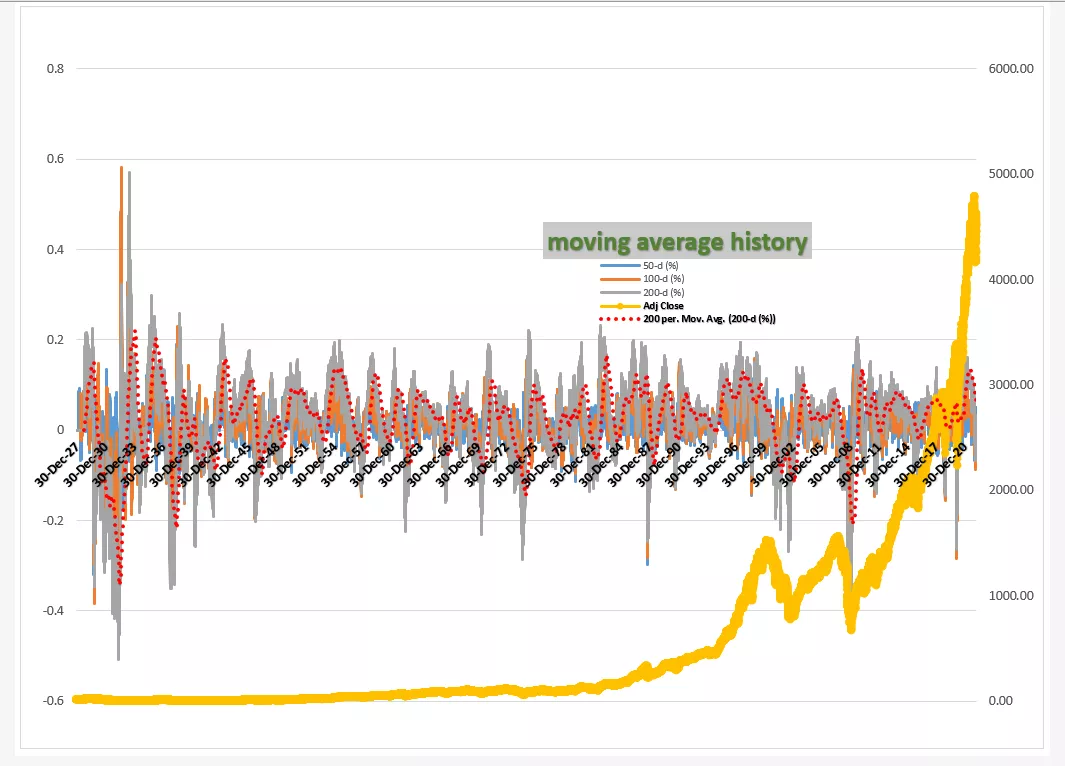

(Click on image to enlarge)

![]()

This is a little hard on the eyes even though it’s not that complicated. But it is really just some iterations of volatility viewed in the sense of how high was the high vs. how low was the low and doing multiple simple operations of this to produce quantities and examine them over time. Remember, it does not matter if this has logical or meaningful causality; it is correlation that counts. If crossing your legs gets four runs batted in in the seventh inning, and it is a reliable probability, and you can trade it, nothing else matters.

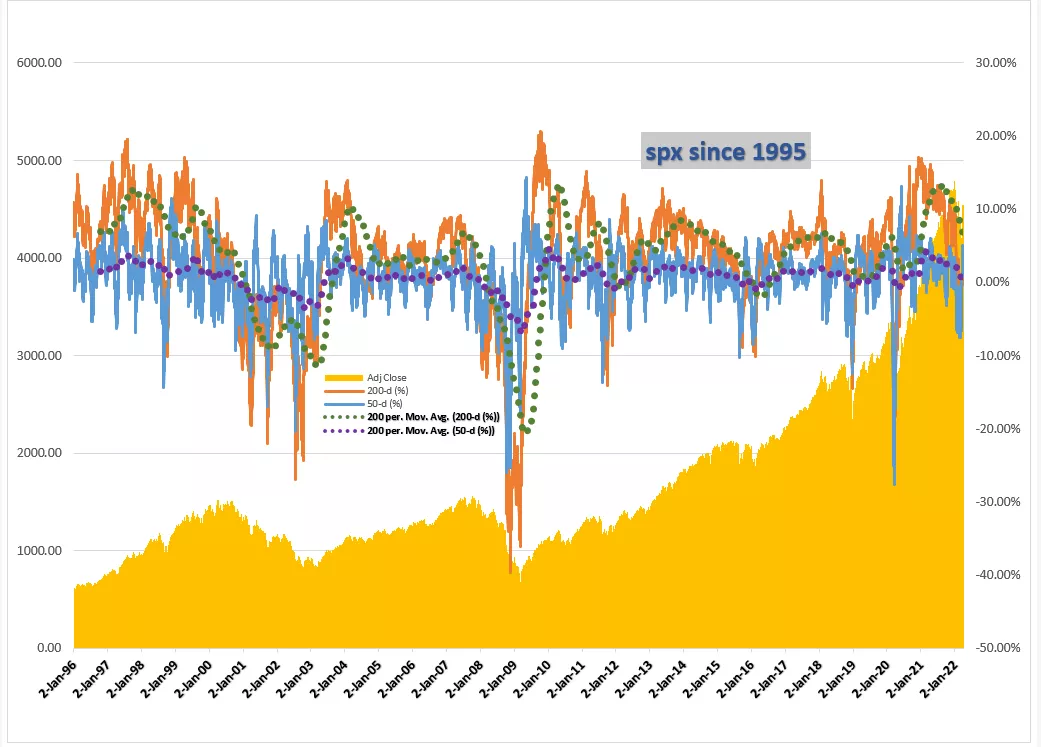

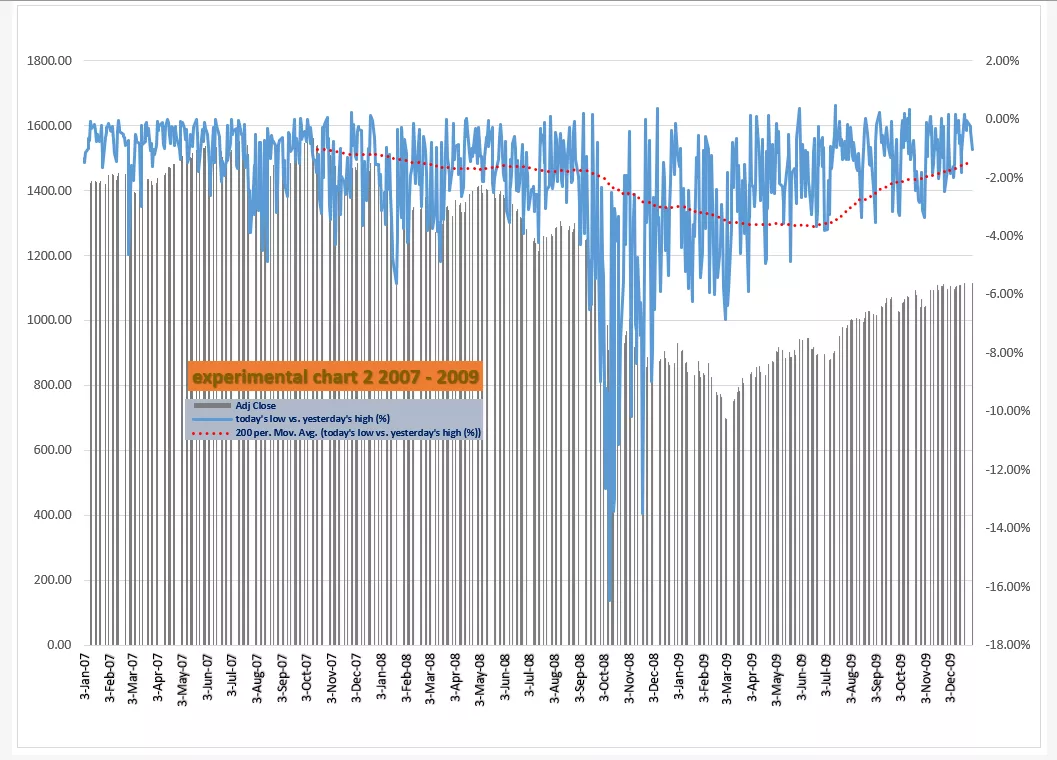

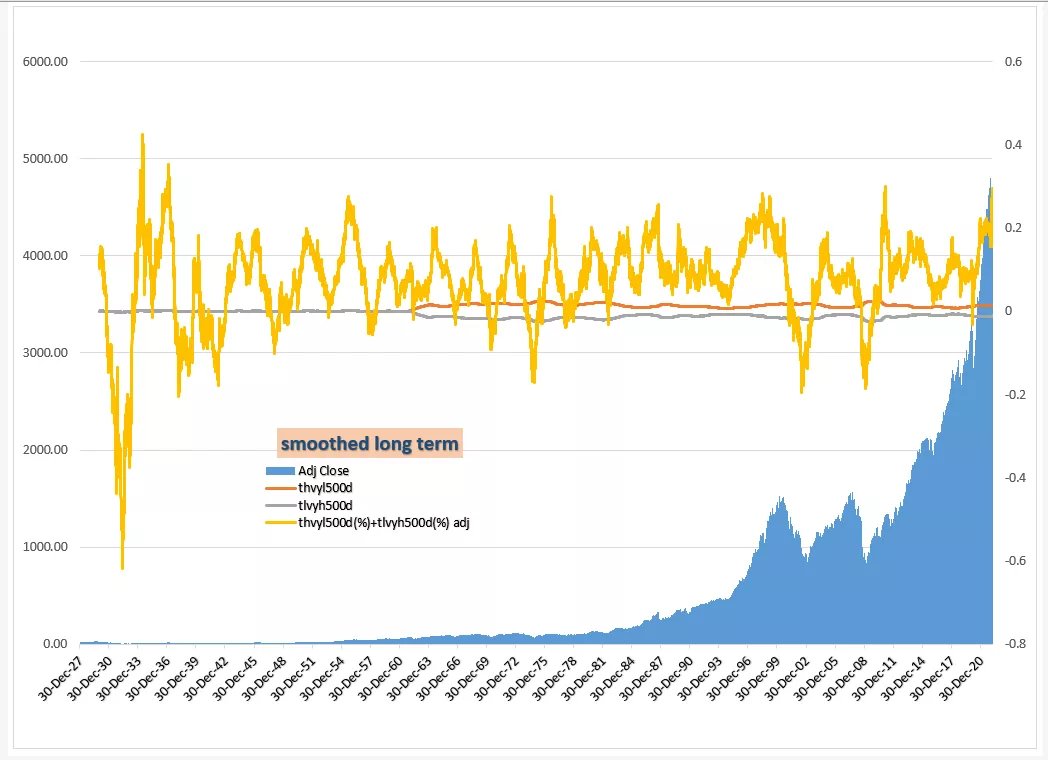

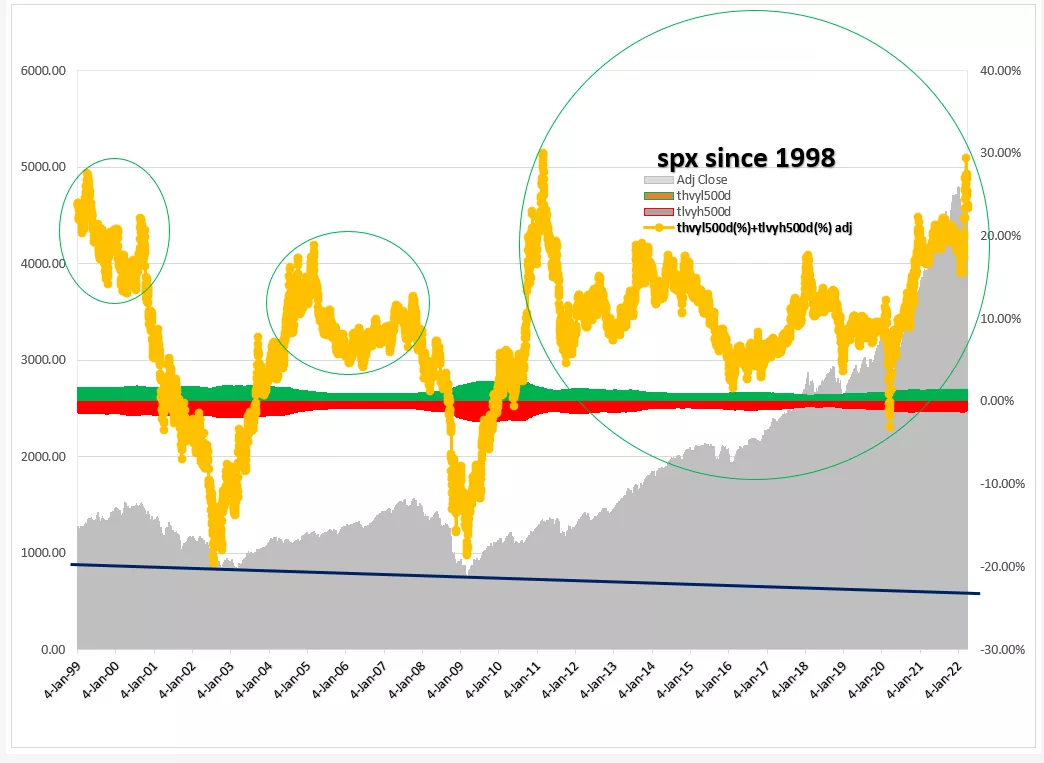

So here’s what you can convert to the world of images from that:

(Click on image to enlarge)

These are just a few examples of basic ways to operate on readily available data and convert them to images in creative ways. The sky’s the limit. What do I think I learned about volatility? Well, the motivation was hearing how the experts describe it. They talk about implied volatility and realized volatility and orthodoxy has grown up around this; that is as powerful as the Knights Templar protecting the Holy Grail. In my view, this is not a good way to investigate and innovate. It’s not a fertile environment. It’s not a welcoming playground. You need to shake it up and move away from orthodoxy and do things people scoff at. And by “shake it up,” the pun is intended. Because in this case, the way my model works is to examine the literal “shake” of stocks moving up and down and how much and for how long and so forth in every way I can think of. I call this real volatility, not to suggest that what others say is unreal but to underscore the physical quality of something that vibrates—like a resonant frequency. I even had a website called “stocks that wiggle” at one time. And just like strings, horns and woodwinds have similarities among differing instruments in each category, stocks within industry segments do the same thing.

The above is not the complete set of keys to the kingdom but it is the basic idea.

Very insightful.

Well Reid, that was an enjoyable read and certainly an amusing way to show the pitfalls of "scientific" market analysis.

Reid and read. Nice pun!

Great read, thanks.