The Performance Of Listed Private Equity

Private equity (PE) involves pooling capital to invest in private companies either in the form of venture capital (VC) to startups or by taking over and restructuring mature firms via leveraged buyouts (LBOs). Attracted by the glamour and potential for lottery-like returns, global PE assets under management had reached $4.2 trillion by 2022. Investors that use PE believe the benefits outweigh the challenges not present in publicly traded assets—such as the complexity of structure, capital calls, illiquidity, higher betas than the market, high volatility of returns (the standard deviation of private equity is in excess of 100%), the extreme skewness in returns (the median return of PE is much lower than the mean (the arithmetic average), lack of transparency, and high costs. Other challenges for investors in direct PE investments include performance reporting data that suffer from self-report bias and biased NAVs, which understate the true variation in the value of PE investments.

Because of minimum net worth requirements, most individual investors don’t have direct access to PE. For such investors, an interesting question is whether investing in the publicly traded (listed) private equity (LPE) of PE firms (such as Blackstone, KKR, and The Carlyle Group) would be an attractive way of accessing the PE space indirectly. It’s an interesting question in light of the fact that investors in LPEs earn both a fund management fee and a performance fee (referred to as the carry), while investors in direct PE earn a risky performance return but pay a yearly management fee. In addition, in times of crisis, while LPE investors still earn management fees but don’t receive a performance fee, investors in direct PE pay yearly management fees while receiving negative returns.

Using the backtest tool at PorfolioVisualizer, we will examine the performance of two ETFs that invest in a diversified portfolio of LPE: the Invesco Global Listed Private Equity ETF (PSP) and the ProShares Global Listed Private Equity (PEX).

PSP Performance

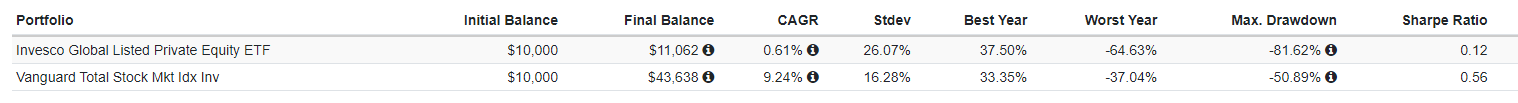

Over the full period for which data is available, November 2006-June 2023, PSP returned just 0.61% per year, underperforming the 9.24% return of the benchmark Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX) by 8.63 percentage points a year. And it underperformed with volatility that was 60% greater (26.07% vs. 16.28%). Its much greater risk can also be seen in its maximum drawdown of almost 82%, 60% greater than the 51% maximum drawdown of VTSMX.

For illustrative purposes only.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Using the regression tool at PortfolioVisualizer, we can also analyze the performance of PSP on a risk-adjusted basis. Using AQR factors including quality, over the period November 2006-April 2023, the fund generated an annualized alpha of -5.75%. As you might expect from a firm investing in private equity, the beta of the fund was 1.28 (28% greater than the market), and it had a statistically significant loading of 0.16 on the value factor. Also of interest was that the fund had statistically significant negative loadings on both momentum (-0.12) and quality (-0.26).

Perhaps surprisingly, given its shockingly poor performance over more than 16 years, according to Morningstar the fund still had almost $200 million of assets under management.

PEX Performance

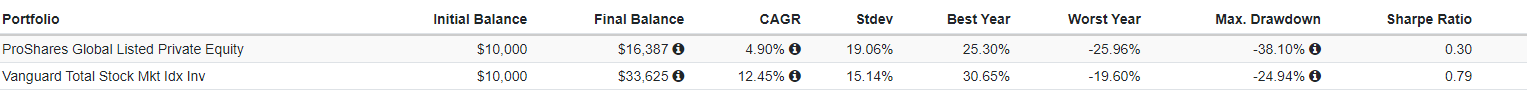

Over the entire period for which data is available, March 2013-June 2023, PEX returned just 4.90%, underperforming the return of 12.45% of the benchmark VTSMX by 7.55 percentage points a year. And it did that with volatility that was 26% greater (19.06% vs. 15.14%). Its much greater risk can also be seen in its maximum drawdown of 38%, 52% greater than the 25% maximum drawdown of VTSMX.

For illustrative purposes only.

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged and do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

Over the period March 2013-April 2023, the fund generated an annualized alpha of -3.64%. PEX’s factor loadings were similar to those of PSP: The beta of the fund was slightly greater than the market at 1.03; it had a statistically significant loading of 0.29 on the value factor; and it had negative loadings on both momentum (-0.07) and quality (-0.12), though neither loading was statistically significant. Given its poor performance, it’s no surprise that the fund had only 9.5 million of assets under management.

To summarize, investors who thought they could achieve attractive returns by indirectly accessing private equity through investing in LPEs have been greatly disappointed.

We now turn to the findings of a new research paper that investigated the performance of LPE compared to that of direct investments in PE. Hrvoje Kurtović, Garen Markarian, and Patrick Breuer, authors of the study “The Risk and Performance of Listed Private Equity” published in the Summer 2023 issue of The Journal of Alternative Investments, used the universe of LPEs on U.S. exchanges to analyze their performance. For their analyses they used Preqin’s database, which contains data on both PEs and LPEs. Their U.S.-based sample started in 2010 and ended in 2019. They chose this time frame to exclude effects related to the 2008 financial and COVID-19 crises.

The authors focused exclusively on LPEs that had buyouts as their main strategy. Their sample comprised 48 distinct U.S.-based LPEs and large PE firms such as Blackstone (IPO in 2007), KKR (IPO in 2010), and Apollo Global (IPO in 2010) but also many small ones whose values ranged in the hundreds of millions: “This large size dispersion makes our sample of LPEs comparable to privately held PEs.” They benchmarked LPE returns against the U.S. total market and the returns of direct investments in PEs. Here is a summary of their key findings:

- LPE performance and valuations were highly correlated with those of unlisted PEs and hence were a good proxy—the Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.501 for the internal rate of return (IRR) and 0.400 for the valuation.

- While direct investments outperformed LPEs in terms of IRR (13.9% vs. 13.2%), there was no statistically significant difference between unlisted and listed funds’ performance.

- LPEs had median leverage of 36.1%, almost double the leverage of the benchmark (19.3%). However, they showed no distinctive performance—LPEs significantly outperformed the benchmark in only three years out of 10.

- Controlling for standard determinants of returns, LPE firms underperformed market benchmarks.

- Controlling for industry effects, LPE firms underperformed.

- Using COVID-19 as an exogenous increase in tail risk, PE firms grossly underperformed, as markets penalized the riskiness and lack of transparency inherent in PE investments.

Their findings led Kurtović, Markarian, and Breuer to conclude:

“PE’s opaque nature complicates an investor’s decision to invest in PE. By examining LPEs, investors can observe direct market signals and rely on audited reports that are not available in the case of a traditional PE. This article provides evidence that LPE performance is highly correlated with PE performance. We conclude that LPEs have leverage double that of the broader market; hence, financial risk is markedly higher within LPEs. However, this increased risk does not translate to higher returns.”

They added: “Investors should be aware of the risks associated with investing in PEs and should consider the potential for underperformance in times of crisis.”

Private Equity Performance

My September 12, 2019, article for Advisor Perspectives provided a summary of the research on the performance of private equity. Unfortunately, it was not encouraging—in general, private equity had underperformed similarly risky public equities even without considering their use of leverage and adjusting for their lack of liquidity. However, the authors of the 2005 study “Private Equity Performance: Returns, Persistence, and Capital Flows” offered some hope. They concluded that the evidence suggests that private equity partnerships were learning—older, more experienced funds tended to have better performance—and there was some persistence in performance. Thus, they recommended that investors choose a firm with a long track record of superior performance.

The most common interpretation of this persistence has been either skill in distinguishing better investments or in the ability to add value post investment (e.g., providing strategic advice to their portfolio companies or helping recruit talented executives). The research does offer another plausible explanation for persistence: successful firms are able to charge a premium for their capital.

Robert Harris, Tim Jenkinson, Steven Kaplan and Ruediger Stucke confirmed the prior research findings of persistence of outperformance in their November 2020 study, “Has Persistence Persisted in Private Equity? Evidence from Buyout and Venture Capital Funds.” However, it was only true for venture capital (not the full spectrum of private equity), as they found that there was no persistence of outperformance in buyout firms.

Investor Takeaways

The late David Swensen, legendary chief investment officer of Yale’s endowment fund, offered these words of caution on private equity investing:

“Understanding the difficulty of identifying superior hedge fund, venture capital and leveraged buyout investments leads to the conclusion that hurdles for casual investors stand insurmountably high. Even many well-equipped investors fail to clear the hurdles necessary to achieve consistent success in producing market-beating, active management results. When operating in arenas that depend fundamentally on active management for success, ill-informed manager selection poses grave risks to portfolio assets.”

Those who choose to ignore Swensen’s warnings still need to understand that, due to the extreme volatility and skewness of returns, it is important to diversify the risks of private equity. This is best achieved by investing indirectly through a private equity fund rather than through direct investments in individual companies. Because most such funds typically limit their investments to a relatively small number, it is also prudent to diversify by investing in more than one fund. Unfortunately, the evidence we reviewed suggests that diversifying by investing in LPEs is not an effective strategy. And finally, top-notch funds are likely closed to most individual investors. They get all the capital they need from the Yales of the world. Forewarned is forearmed.

More By This Author:

The Quality Factor And The Low-Beta Anomaly

Social Media And Inequality In Venture Capital Funding

Gold As A Safe-Haven Asset

Performance figures contained herein are hypothetical, unaudited and prepared by Alpha Architect, LLC; hypothetical results are intended for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is not ...

more