Persistently Disappointing

If you’ve ever read a prospectus (or, for that matter, an S&P DJI research report), you know that “past performance is no guarantee of future results”. At one level, if you understand that, you understand the most important thing about S&P DJI’s Persistence Scorecards. For the U.S., Europe, Latin America, and Canada (with Australia coming soon!) our recently released Persistence Scorecards are unanimous in showing that historical outperformance is not a predictor of future outperformance.

At a deeper level, why do we care? We know from SPIVA® and other data that most active managers underperform most of the time. But even in the most challenging years, there is a range of active performance results; some managers will always do better than others, regardless of how many outperform passive benchmarks like the S&P 500®. Do the top performers get there because of genuine skill or merely because of good luck?

There is, after all, no theology that precludes the existence of a (presumably small) subset of genuinely skillful active managers. If such a group existed, how would their abilities be evidenced in performance data? As a thought experiment, we can consider a hypothetical set of managers who achieve above-median performance in a particular period, and ask how they perform in subsequent periods.

If every above-median manager in period one got there simply by being lucky, we would expect half of them to be above median again in period two. If the repeat-success rate were substantially above 50%, we might begin to suspect that the above-median managers were genuinely skillful. But if fewer than 50% of the period one successes were above median in period two, that would support the view that their period one success was due to luck. If we understand something about persistence, we may be able to make inferences about manager skill.

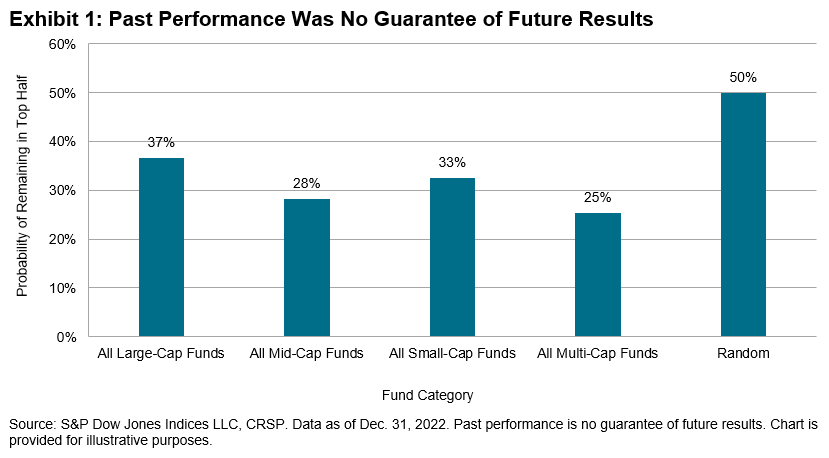

And that is exactly what the Persistence Scorecards let us do. Exhibit 1 illustrates, using 10 years of U.S. equity data and asking to what degree above-median performance in the first 5 years predicted above-median performance in the second 5 years. The answer is: not at all. In every fund category, the winners in years 1-5 were unlikely to repeat their success in years 6-10.

There are, of course, other ways to test for persistence. We could examine performance relative to a benchmark rather than to a peer group, with different lookback periods (one year or three years rather than five years), with different cutoffs (quartiles rather than halves), and for different asset classes (bonds as well as stocks). Our Persistence Scorecards do all of these things and, mutatis mutandis, the results are the same.

Results produced by genuine skill are likely to continue, while those due to luck are likely to prove ephemeral. The data suggest that good active performance often owes more to luck than to skill.

More By This Author:

A Quick Look At Key USD Indices And Fixed Income ETF Flows This Year

Combining Sectors And Sustainability

The S&P GSCI Cooled In April As Inflation Cooled

Disclaimer: See the full disclaimer for S&P Dow Jones Indices here.