Expecting A Market Downturn? Follow The “Noah Rule”

In his letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders for the fiscal year 2001, Warren Buffett made one of his now-famous pronouncements: “Predicting rain doesn’t count, building an ark does.”

Buffett admitted to forecasting some of the market turmoil that year, which was exacerbated by 9/11, and yet he failed to convert thought into action. Thus, he violated what some investors now call “the Noah rule,” named for the ancient prophet who saved himself, his family and a few million animals by building a ship in anticipation of a great flood.

Predicting a major economic or financial event—whether that’s a recession, market downturn or even your own retirement—requires that you also take action. Otherwise, your prediction was meaningless.

Alarming Number of Americans Unprepared for Retirement

Unfortunately, an alarming number of Americans aren’t saving for retirement. They may have “predicted the rain,” but for whatever reason—and there are many we could point to—they haven’t gotten around to “building the ark.”

And according to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decision Making, four in 10 Americans are so short on cash right now that they wouldn’t be able to afford a $400 “emergency expense.”

This is despite a stellar jobs market and booming stock market.

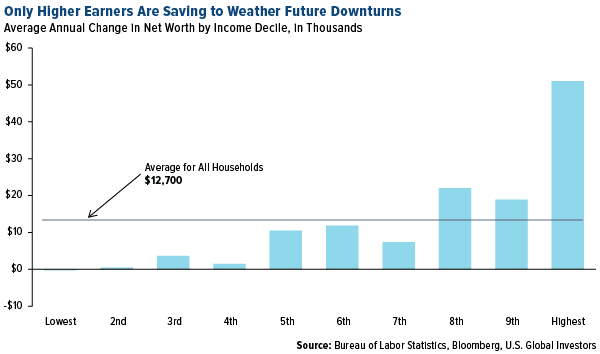

So who’s saving in America, and who isn’t? A recent report by Bloomberg’s Aaron Brown tackles this very question by breaking down U.S. households into 10 separate income brackets. Unsurprisingly, it’s the earners at the top who are able to save the most, with the very highest earners’ net worth growing an average $51,000 on an annual basis. Households in the bottom decile, meanwhile, end up losing an average $300 year-over-year, as they must borrow or sell assets to support spending. This group is most vulnerable and “will face problems in the next recession,” Brown writes, adding that “they may find it difficult to climb to financial security.”

(Click on image to enlarge)

What can be done about this to ensure more people are able to save and invest for when the “rain” starts to fall?

Interestingly, Brown makes the case that expanding entitlement programs isn’t the answer. Nor is a wealth tax such as what presidential contender Elizabeth Warren has proposed.

“The U.S. already redistributes enough income to allow low-income households to spend more per earner on average” than many higher-income households, Brown says.

Instead, a “better path to reducing economic insecurity” would be to shore up government pensions and Social Security, among other strategies.

Singapore: A Masterclass in Fiscal Responsibility

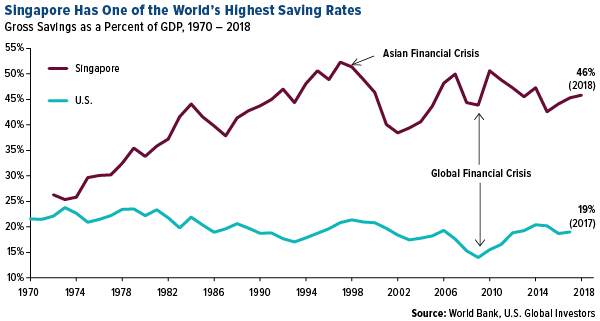

Brown’s idea is incredibly similar to what Singapore already does, starting with its Central Provident Fund (CPF)—a sort of Social Security-401(k) hybrid that all Singaporeans are required to participate in. The CPF not only provides participants with retirement earnings but can also be withdrawn before retirement for specific housing and medical expenses. Both employees and employers are responsible for making contributions—20 percent of income on average for the former, 17 percent for the later—which are then invested to earn about 5 percent annually.

The CPF program, launched in the mid-1950s, is often cited for helping residents of the Asian city-state become among the world’s most fiscally responsible. Compared to people in most other developed countries, Singaporeans save a much larger portion of their earnings as a percent of GDP. A recent study, in fact, found that six in 10 Singapore millennials—those aged 25 to 34—currently save over 20 percent of their salary. Most are not just well on their way for retirement, but they’re even more prepared for retirement than their middle-aged counterparts, according to the study.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Singapore has managed to do this without levying huge taxes to support entitlements.

Personal income is taxed progressively between 2 percent and 22 percent, and because there’s no capital gains tax, dividends paid by Singapore-resident companies are completely tax-free.

Corporations pay a reasonable 17 percent on average, and there’s no payroll tax.

What this means is that Singapore’s tax revenue as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) stands at only 14.1 percent, about two and a half times lower than the OECD average of 34.2 percent.

Some might initially think that lower taxes would result in a lower standard of living, with crumbling infrastructure and services. On the contrary, Singapore’s infrastructure is regularly regarded as the best in the world, with the World Economic Forum (WEF) ranking it first in quality of roads, railroad density and efficiency of air transport and seaport services. The city-state came in first overall in the WEF’s Global Competitiveness Report 2019, followed by the U.S. Hong Kong, the Netherlands and Switzerland rounded out the top five.

Majority of CFOs Believe a Recession Will Strike in 2020

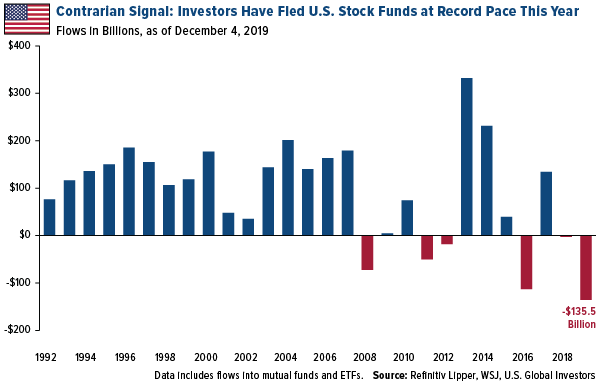

But back to the idea of preparing for rain. The latest quarterly release of the Duke University/CFO Global Business Outlook shows that a majority (52 percent) of chief financial officers (CFOs) in the U.S. believe a recession will strike in 2020. Fifty-six percent say they’re already taking steps to prepare for a downturn, including raising cash levels and reducing debt.

This is in line with investor behavior right now. So far this year, investors have pulled as much as $135.5 billion from U.S. equity-focused mutual funds and ETFs. That’s the biggest 12-month withdrawal on record going back to 1992, even as stocks have had a phenomenal year, increasing 26 percent.

(Click on image to enlarge)

A lot of this money has turned up in “safe haven” investments such as bonds and money market funds, but as I said last week, with yields so low right now, investors might be better served by overweighting gold.

Besides, I think a lot of investors will end up regretting not participating in this market, which has largely shrugged off the political noise and responded positively to the news that the U.S. and China have finally reached a major agreement in their ongoing trade spat.

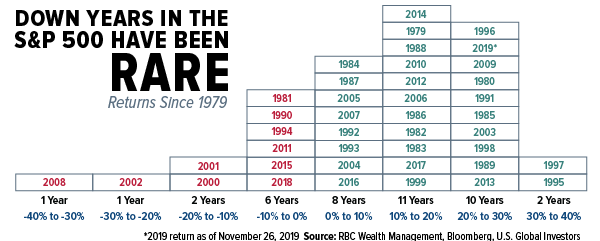

On a final note, I’d like to share with you a table that illustrates just how rare down years have been in the S&P 500. In only 10 out of the past 40 years, or 25 percent of the time, stocks ended in the red for the year, and of those instances, only four had losses greater than 10 percent. Three-quarters of the time, the market was up for the year, with healthy returns of between 10 percent and 30 percent occurring about half the time.

(Click on image to enlarge)

A recession or market pullback always seems to be right around the corner, but it’s worth remembering that, historically and statistically, stocks have gone up far more often than they’ve gone down. The amount of money that’s been taken off the table this year may be overdone, not to mention premature.

Disclaimer:

The S&P 500 Stock Index is a widely recognized capitalization-weighted index of 500 common stock prices in U.S. companies.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation ...

more