Everything You Were Taught About Risk Is Wrong

In my experience, “Risk” is the single most misunderstood concept in finance. Volatility, risk and uncertainty are all terms that are used interchangeably on Wall Street. The confusion is in no small part due to the strong influence of “Modern Portfolio Theory”, which continues to live on despite the fact that it makes no sense. At the core of MPT is the (flawed) idea that risk is equivalent to price volatility. It’s remarkable to me that so much complex math has been built on the back of such a dumb assumption.

Risk = Volatility?

The willingness of the financial community to accept this assumption is astounding. Any reasonably intelligent person who stops to think about this for 5 minutes will realize how nonsensical it is:

- Volatility measures the extent to which a stock price has fluctuated historically, both upward and downward over an arbitrary time period (e.g. a month). Risk, on the other hand, has more to do with the future possibility of a permanent loss on your investment. How did we end up equating these two very different concepts?

- In any case, volatility measures the fluctuation in the market share price, not the underlying value. As with any market, the price can fluctuate quite independently of the underlying value.

Accepting the academic definition will logically lead you to some bizarre conclusions, as Warren Buffett explains:

“For owners of a business— and that’s the way we think of shareholders— the academics’ definition of risk is far off the mark, so much so that it produces absurdities. For example, under beta-based theory, a stock that has dropped very sharply compared to the market— as had Washington Post when we bought it in 1973— becomes “riskier” at the lower price than it was at the higher price. Would that description have then made any sense to someone who was offered the entire company at a vastly-reduced price?”

Risk and Return

One of the great “insights” of MPT is that higher returns are correlated with higher risk. As you take on more risk, you expect to be compensated with a higher return. Intuitively this seems to make sense. The flaw with this argument however is that it treats risk and return as two separate variables. The fact is that over a long enough time frame, risk becomes a component of return. Put another way, if you’re constantly taking risks, then sooner or later your returns are going to suffer

“greater risk does not guarantee greater return. To the contrary, risk erodes return by causing losses…By itself risk does not create incremental return; only price can do that” Seth Klarman, “Margin of Safety”

If you want to maximize returns, in fact you need to minimize risk. As Benjamin Graham described over 80 years ago, the best protection against a loss is to ensure that you have a “Margin of Safety”. This is defined as the difference between what you pay for a stock and your estimate of its intrinsic value. It’s purpose is to absorb the impact of uncertainty.

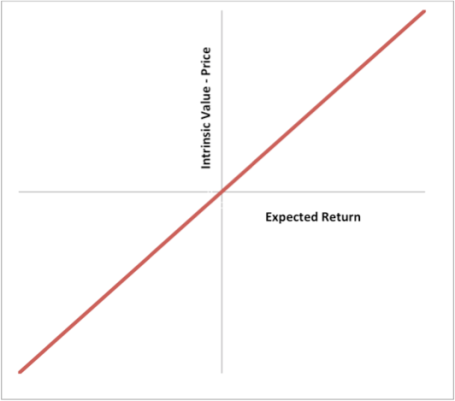

Consider the following chart. If there were no uncertainty to an investment, then the expected return of a stock would simply be equal to the intrinsic value less the market price paid (the “Margin of Safety”). (Of course this situation would not last long as the market would soon snap up all these risk-free opportunities).

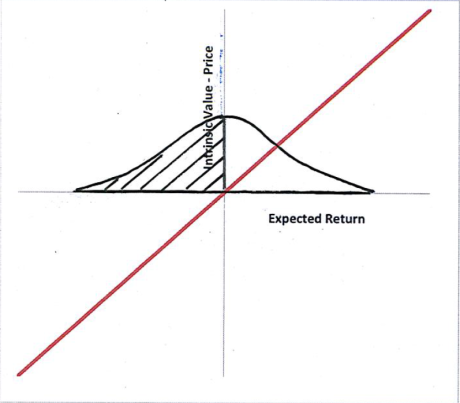

In reality of course, when we make an investment our estimates are subject to extreme uncertainty and we understand that there are a wide range of different outcomes.

Your average investor tends to invest on the basis of only one outcome (which of course is positive). They drastically underestimate the uncertainty involved in this outcome and fail to build in a sufficient margin of safety. These investment decisions can be represented by the chart below. While the investor is focused on the outcomes to the right of the chart, they fail to consider all the (equally possible) negative outcomes to the left (denoted by the shaded area).

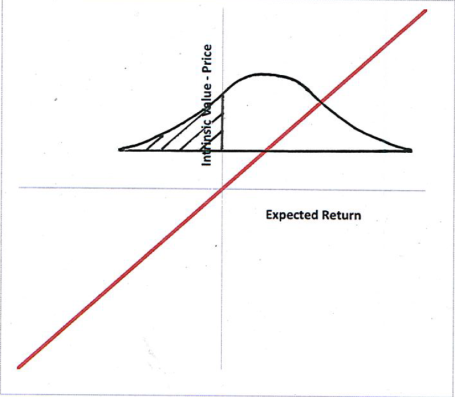

Great investors make decisions that can be represented by the next chart. They understand that there are a wide range of outcomes, both positive and negative. Therefore they build in a significant “margin of safety”. Of course that margin will not be sufficient in all cases to prevent a loss, and the investor knows that. But, the investor has reduced the number of circumstances in which they are likely to lose (the shaded area is smaller). Over the long haul they will gain more often than they lose.

“Our goal is not to outperform all the time – that’s not possible. We want to outperform over time” John Paulson

Learning from your mistakes

This brings us to learning from your mistakes. Most investors don’t understand the role of randomness, so they end up learning the wrong lessons. They assume they have made a good investment when the outcome is positive, then they beat themselves up when the outcome in negative. In his excellent book, “The Most Important Thing”, Howard Marks explains how good investors should divorce the quality of the decision from the outcome.

“The correctness of a decision can’t be judged from the outcome. Nevertheless that’s how people assess it. A good decision is one that’s optimal at the time it’s made, when the future is by definition unknown. Thus, correct decisions are often unsuccessful, and vice versa” Howard Marks, “The Most Important Thing”

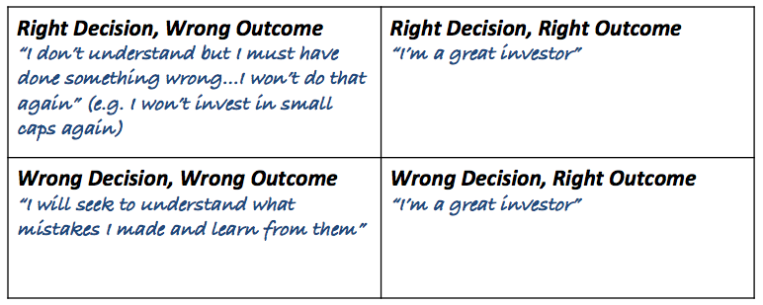

The table below shows how a poor investor reacts to various scenarios (essentially summarizing much of what Marks lays out in his book).

We see that in two of the scenarios the investor’s reaction is actually harmful. Where they have made the right decision but achieved the wrong outcome, they end up learning the wrong lesson. And when they made the wrong decision, but were bailed out by luck, they fail to learn any lessons at all.

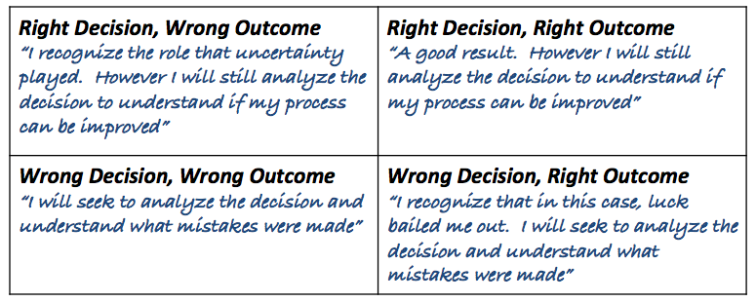

A good investor will react to the various scenarios as set out in the next table:

This is harder than it looks because we need to be honest with ourselves about the process that we went through to select an investment. George Soros used to keep an investment diary so that he could go back after the event and understand his original reasons for investment.

“I kept a diary in which I recorded the thoughts that went into my financial decisions on a real-time basis…The experiment was a roaring success in financial terms – my fund never did better. It also produced a surprising result: I came out of the experiment with quite different expectations about the future” George Soros, Alchemy of Finance

The way that we set up StockViews, it was intended to fulfill this function: A real-time diary of all your investment decisions. That way, you can look back after the event and it forces you to be honest with yourself about why an investment was made (it’s also harder to cheat yourself when the record is public!).

“Only by cross-referencing our decisions and the reasons for those decisions with the outcomes, can we hope to understand when we are lucky and when we have used genuine skill, and more importantly, where we are making persistent and recurrent mistakes” James Montier, “The Little Book of Behavioral Investing”

Opportunity in Risk

Equating risk to volatility is enduringly popular because it satisfies our need to put a number on it. However adopting Wall Street’s definition of risk will make you a worse investor, since you will fail to understand the true nature of risk and how to cope with it.

The reality is that risk cannot be measured exactly. But that doesn’t mean we can’t have an appreciation of it as a concept and factor it into our investments. You won’t always always avoid a negative outcome, but it will allow you to make sense of things that others can’t. And therein lies the opportunity – you see risk where others see none and you see opportunity where others only see risk.

“When everyone believes something is risky, their unwillingness to buy usually reduces its price to the point where it’s not risk at all. Broadly negative opinion can make it the least risky thing, since all the optimism has been driven out of its price.” Howard Marks, “The Most Important Thing”

Disclosure: None

Right.... it's time to look at investing like navigation... maps are used to plot a course, but continuous adjustments to the real environment are made. When the map is mistaken for reality, you get LTCM, or some such. Being honest with yourself can seem painful, until you seriously consider the alternative...

The funny thing is the rates you get on many investments doesn't even cover risk making them all terrible. I fully agree with the author that investors are being badly misled about the risk they are indulging in, but I can't blame them. In a programmed economy with socialistic tendencies it is virtually impossible to read market signs. That is why they always eventually crash in the most disasterous ways.

I completely agree with your article. Risk is the 'effect of uncertainty on objectives'. In this definition, uncertainties include events (which may or may not happen) and uncertainties caused by ambiguity or a lack of information. It also includes both negative and positive impacts on objectives. Many definitions of risk exist in common usage, however this definition was developed by an international committee representing over 30 countries and is based on the input of several thousand subject matter experts.