Class Action Investor Lawsuit Raises Facebook IPO Valuation Issues

Might a company be sued for pricing its initial public offering too high? Lawsuits filed in 2013 charge that Facebook (FB) set its IPO valuation too high. That headline resurfaced in December 2015 when U.S. District Judge Robert Sweet ruled that he would allow the cases to proceed as class-action lawsuits.

Reuters reports that the plaintiffs are retail and institutional investors who claim they lost money buying Facebook shares at inflated prices. They say their decision to invest was influenced by Facebook’s projected earnings from the mobile device market. Those were later lowered and so, plaintiffs say they overpaid for their stock.

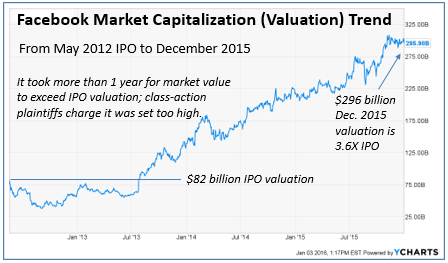

In its May 2012 IPO, Facebook gave itself an $82 billion valuation; that figure calculated by multiplying the shares outstanding by the $38 share price. As the chart below shows, the valuation fell significantly in the secondary market and took more than a year to recover. It climbed thereafter, ending 2015 at $296 billion. [Note: The share price closed 2015 at $105, 2.8X the IPO price. The valuation increased 3.6X because additional shares were issued after the IPO.]

From a long-term perspective, one might wonder what the problem is, given that it has climbed nicely. But these lawsuits were filed when the market price was below or near the IPO price, when the plaintiffs felt they had paid too much for their stake.

Two mirroring questions emerge from a lawsuit over IPO valuation. How should a company set one? How might investors assess it?

Valuation is important. Yet, remarkably, it isn’t a required disclosure in an offering document. Investors must calculate it. Unfortunately, many don’t know how to, feel uncomfortable doing so or just forget to.

So, central to this lawsuit is something that is both important and undisclosed. That’s ironic.

Did Facebook fix its valuation too high? That implies there is a “right price”—an unlikely argument. A stock’s intrinsic value has been the holy grail for capital market theoreticians for more than a century—they are still looking. The question also suggests that Facebook breached a duty to investors by setting it “too high”—it had no such obligation.

According to their attorney’s website, the plaintiffs don’t say that Facebook got the number wrong. Rather, they claim that the company wasn’t fair and forthright with information it knew investors used to assess it. They say Facebook presented projections during its IPO roadshow that it lowered the day after the IPO. Also, that analysts at its underwriters—Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs—cut their earnings estimates during the roadshow and only disclosed it to select clients.

The case is Facebook Inc IPO Securities and Derivative Litigation, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, No. 12-md-02389 and you can read the plaintiff’s brief here.

My guess is that Facebook will settle the case to get rid of the distraction. I also imagine that “Morgan, Morgan and Goldman” will contribute to the pot; it is bad for business if their best IPO customers are disgruntled and there are unicorns in the stable that want to go public!

However, should the case go to trial, the focus will be on whether the disclosure was wrongful, not whether the valuation was excessive. Key questions will be what did Facebook executives know about their projections and when did they know it? Were they uniformly transparent when they felt the need to lower them?

So, this case is unlikely to shed light on how companies should set their valuation or how investors might assess one. Too bad in a way, the arguments would be interesting! On the other hand, few want courts to decide those questions…and neither, I’ll bet, would Judge Sweet.

The fact is that no one knows how to reliably value a venture stage company. That, in part, is why IPO issuers routinely state that their valuation is set arbitrarily and warn that it may drop after the offering.

To price an offering, broker-dealers estimate what the stock will trade at in the secondary market, then recommend a price that is 15 to 20 percent less. This rewards their best customers with an IPO pop; they can sell to hoi polloi investors eager to get shares. These investors are valuation savvy; hence their input is critical when the valuation for a Wall Street IPO is set.

Sometimes the desired outcome doesn’t happen. There is no pop or it is small or the price falls below the IPO price, as Facebook’s did (e.g., Ali Baba Group [BABA], Groupon [GRPN]). No one has a crystal ball for the market and a company may be unable to forecast earnings accurately.

One thing is predictable, however. Many venture-stage issuers will raise capital using a public offering in the years ahead. JOBS Act reforms like Reg. A+ and equity crowdfunding offerings will expand the ranks of such companies and few will have a phalanx of stock analysts who evaluate their valuation. As a result, more IPO investors will feel they overpaid.

Unicorns present valuation challenges. So do horses and ponies; companies with smaller valuations. Is a fresh-out-of-the-oven start-up overvalued at $50 million but not at $40 million? At $25 million? At $5 million? Getting the answer right is a big determinant of whether an investor makes money.

One way to make valuations easier to assess is to have better data. The entire capital ecosystem would benefit if two comparisons could readily be made.

- The valuation of comparable companies, be they private or public.

- The valuation trend line for the issuer—from seed round to IPO.

Third party data aggregators could provide this data inexpensively if securities regulators require that all offering documents disclose the valuation.

Real estate websites show the benefit of such information for home buyers and sellers. Comparable benefits are possible in the capital markets.

Better context would encourage informed democracy in the capital markets because, again, no one really knows how to value a venture-stage company. Better context would also promote democracy in capital markets. Issuers and sophisticated investors know the second data point and do all they can to acquire the first one through their networks.

The utility of these two data points is obvious. The question is whether to make it easier and less expensive for anyone to acquire.

Until better data is ubiquitous, valuation will be presented as a black art, more mysterious than it need be. The driver behind any evaluation of a given number is easy to understand. I refer to it as The Next Guy Theory; an investor will pay what he thinks the Next Guy will pay, less a discount. There is variation in how try to discern that, just as there is variety in how pundits try to project winners in sports or politics. No one does this reliably well, in all industry sectors.

The Facebook plaintiffs claim that the company’s short-term projections for the mobile market set their willingness to invest. In effect, they say “we would not have invested at the IPO price had we had a better forecast.”

I’m skeptical, it rings of sophistry. The rise in Facebook’s valuation suggest it was correct on projecting success even if its timing was off. I think there was a collective misread of what the Next Guy would pay. Or maybe, the market has one now!

The point is that better valuation data will improve market forces by providing everyone with what the valuation savvy use to assess one. It will reduce froth, which is good for capitalism.

Another solution is to make valuation less important at the time of investment. That is, to use capital structures that are flexible with respect to how the rewards of ownership are eventually distributed.

Venture capitalists do this when they invest in a private company by securing deal terms that provide price protection (e.g., price ratchets, liquidation preferences). If subsequent events indicate that their buy-in valuation was too high, their stake is retroactively increased (i.e., their buy-in valuation is reduced).

The Fairshare Model, the subject of a book I’m writing, adapts this concept to an IPO. The Fairshare Model is a performance-based capital structure for companies that raise venture capital via a public offering. No company has used it but some will, once enough investors express interest in it.

A company that uses the Fairshare Model has two classes of stock—one trades, one doesn’t, both vote.

Pre-IPO and IPO investors get the tradable stock, known as Investor Stock. For value already delivered, employees get it as well.

For their future performance, employees get the non-tradable stock, called Performance Stock.

Based on criteria set by the company and described in its offering document, Performance Stock converts to Investor Stock. The conversion rules change if both classes of stock agree to the change. The measurements could be the market price of Investor Stock, financial performance (e.g., sales, profit), operating milestones (e.g., product release, clinical trial results) and/or social impact.

The Fairshare Model provides a way to minimize valuation risk because it creates incentive to offer IPO investors a low valuation. If a rise in the price of Investor Stock drives conversions, Performance Stockholders will want to set the IPO valuation low because it helps to assure conversions.

The Fairshare Model can also reduce failure risk because it can help companies attract and manage human capital. In addition to pay, benefits and stock options on its Investor Stock, a company can offer employees an interest in its Performance Stock. It pays off when they, as a team, meet the conversion criteria.

The essence of the Fairshare Model is that it balances and aligns the interests of employees and investors—labor and capital. That is good for capitalism too!

In conclusion, harm from valuation risk is certain to rise as the JOBS Act reforms like , but lawsuits are an ineffective response. We need better valuation data and deal structures that reduce valuation risk.

The Fairshare Model will be published about five months after 750 people pre-order a copy from Inkshares, a new styl

more

e publisher that decides what projects to back based on reader support (i.e., rewards based crowdfunding; a discounted price on a signed copy in exchange for a pre-order)..

e publisher that decides what projects to back based on reader support (i.e., rewards based crowdfunding; a discounted price on a signed copy in exchange for a pre-order)..

They have a credible argument and it is not the first time investment banks have screwed people over an IPO. The issue over the fact the stock price has risen is not the point. The point is the misinformation and/or rigging in the IPO. Sadly, most IPOs aren't friendly or tailored to small investors but to big investors who get the upper hand. It's a dirty business and I'm glad people are exposing it and hopefully reforming it with lawsuits.

Your cynical comment led me to wonder, did anyone with knowledge of the forthcoming reduction in ST projections short the stock? Less cynically, the desire to head off short sellers may be why FB lowered its guidance so quickly.

In any case, the point is that no one knows how to evaluate venture-stage deals. Better valuation data and IPO deal structures that are valuation-elastic, like those VCs get, are promising solutions.

One thing that would help is the barring of companies from pushing non-GAAP results onto investors to sell their company. This is especially prevalent with tech companies and should be an outrage to accountants and regulators. It's akin to someone selling tin pots labeled Costco tin pot and then covering up the label and saying they're from Saudi Arabia and 1 in 10 have genies inside.

There is little to no regulation to protect investors these days. Buyers beware. This may be why direct investment in stocks have plummeted to all time lows.

There are many non-GAAP figures that can be relevant to a business.. Please provide an example of what you consider to be an inappropriate use of one.

Meanwhile, I'll give you a GAAP figure that is expensive to generate and doesn't provide useful information to any reader of a financial statement that I can think of--stock compensation expense. Theoretically, I don't see why it makes sense to report shareholder dilution an income statement matter. Practically speaking, everyone I can think of adjusts it off in their analysis--evidence that it is not useful. Dilution is relevant but the way GAAP handles this is not helpful.

I share your desire to see stronger investor protections but I believe better valuation data will be more beneficial than a change in accounting standards..

If you invest in other countries you will see the adverse effect of heavy stock dilution in closely held companies. It has an effect when abused and that's why disclosure decreases the effect so you don't need to overly concern yourself with US stocks.

Well said.

This is an example of how the best underwriters let the fact that there was great demand for the shares cloud their judgement.

Agreed!