Monetary Policy Was Even Worse Than We Thought

Image Source: Pexels

In a recent post, I made the following claim:

So why wasn’t the overall inflation rate transitory, as many had predicted? The answer is simple. All of the cumulative inflation since 2019 is demand side, and demand side inflation is permanent. PCE inflation over the past 5 years has exceeded the Fed’s 2% target by a total of nearly 8%. NGDP growth has exceeded 4%/year by a total of roughly 10%. That’s the entire problem—supply shocks have nothing to do with it. If anything, we’ve had enough positive supply shocks (mostly immigration) to hold inflation 2% below the level you would expect from the extreme demand stimulus that was provided. The Fed actually got lucky.

I need to revise that final line to: The Fed actually got very lucky.

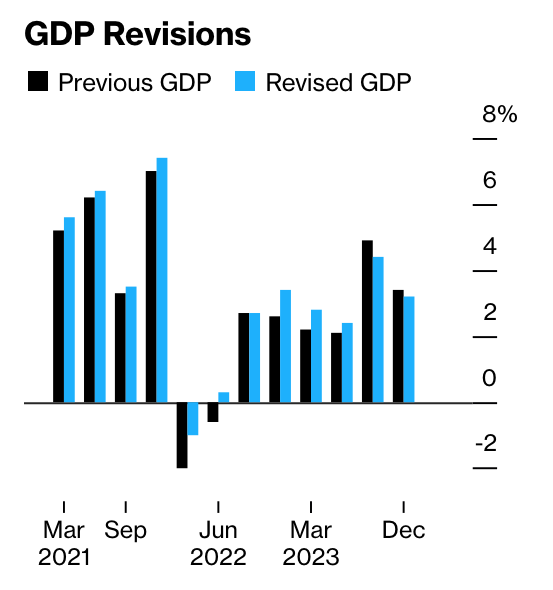

Today, the government announced revised estimates of GDP growth during 2021-23. Bloomberg has a graph showing the data for real output, but NGDP was revised by a similar amount:

A few observations:

In 2022, I had a debate with some commenters as to whether we were in recession. I said we were not, and they pointed to two negative quarters of real GDP growth. I replied that this was not the official NBER criterion and that other data showed a strong economy. The revised data shows that there weren’t even two negative quarters. There was no recession in 2022, by any reasonable criterion.

In my previous post cited above, I mentioned a 10% overshoot of NGDP growth. With the revised data the overshoot was 11.5%, providing evidence that monetary policy was even more excessive than we had thought, and also further confirms that “supply shocks” were not the problem. A strong supply side held excess inflation to roughly 8%, or 3.5% below what one would have expected from monetary policy alone. On the plus side, the economy’s potential may be a bit higher than we had assumed, probably due to more immigration, but perhaps also reflecting an uptick in productivity.

Previously, the data had showed much stronger growth in GDP than in GDI, even though both are conceptually identical. Gross domestic income was revised upward much more sharply than GDP, so that gap is now considerably smaller.

Those previous estimates of GDI growth (yellow bars) never made any sense given the strong growth in employment.

More By This Author:

When Policy Goals ConflictWhy The Experts Are Wrong About Inflation

Carbon Taxes Vs. Regulation