The Magic’s Gone

For the magic trick to work, it has to be credible. The audience has to be given something concrete upon which they will suspend their disbelief. Quantitative Easing was just such a trick, though only the public held onto any basis for success. You still hear it all the time, how QE was “money printing”. That was the trick.

It doesn’t work if there is the slightest doubt. We know as late as 2013 even policymakers had them, the Dallas Fed President’s hushed “monetary head fake”. That actually makes it sound better than it was, that officials were doing the faking rather than being in the group who fell for it.

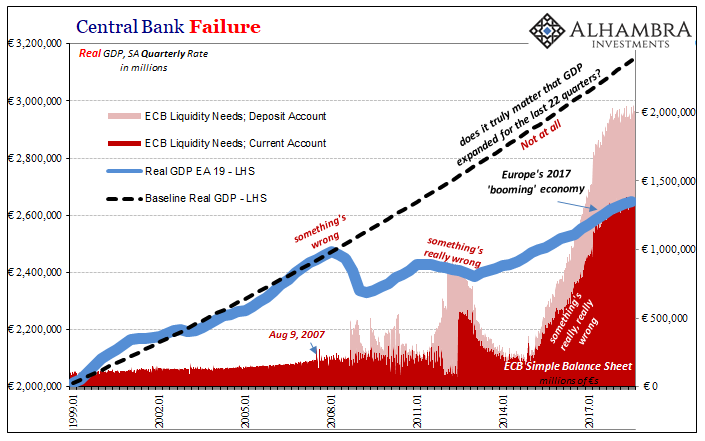

No, QE didn’t work. Not in the slightest. Even as a technical matter it was a pure failure. Proponents say that it lowered interest rates at the very least, no matter what might’ve been the results further down the line. Again, nonsense. Everywhere QE was instituted bond rates had already fallen often quite substantially long before whichever central bank booked its first purchase.

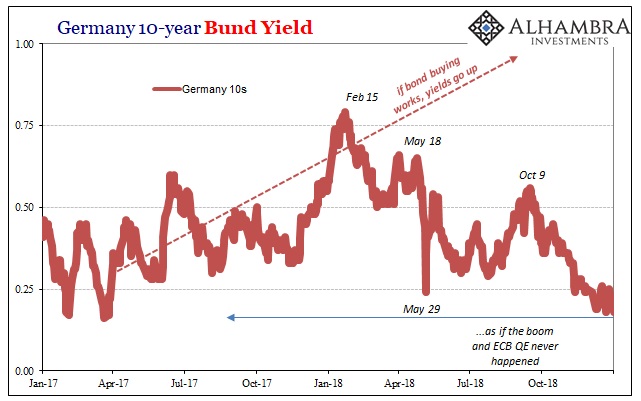

In Germany, for example, the 10-year bund yield was near 3.60% in April 2011 and heading higher. By the time the ECB was forced into rate cuts later that year, it was already under 2.00% for the first time. When QE was begun about three and a half years later, the benchmark 10s were near zero without requiring a single transaction against any of the NCB’s accounts (Europe’s PSPP was carried out by National Central Banks).

In early 2019, now as QE has ended the yield for Germany’s 10s is practically zero once again. In trading today, it fell to just 18 bps, almost exactly where it was in April 2015. Mario Draghi says Europe was booming in 2017, yet Germany’s yield trajectory reflects a very, very different economic interpretation.

Notice how the further Europe’s economy falls behind its pre-crisis baseline, the lower interest rates tend to stay no matter what or how much “stimulus.” This is no magic trick, nor is it a coincidence.

Low yields were only the theoretical first step, however. We are taught how low-interest rates signal stimulus when in fact they declare its very opposite.

According to the ECB, it would buy German bunds, bobls, and schaetzes as well as paper issued by other European sovereigns from European banks. It was a simple asset swap, government bonds in exchange for bank reserves (parked at either a reserve account or on deposit with the ECB). Having given up a yielding asset for a non-yielding one, these banks were expected to do something productive (like loans) with those reserves

Instead, banks used them combined with their own capacities to buy more bunds, bobls, and schaetzes (as well as paper issued by other European sovereigns). They did very little lending. Very little.

Persistently low-interest rates tell us everything we need to know about the true state of any economy. If banks are not convinced of economic growth, therefore the financial opportunity to do something with these bank reserves, then that’s the end of the story as far as the chances for any recovery. Rather than go into risky assets, they continue to favor the most highly liquid instruments even if (especially if) the central bank is buying them, too.

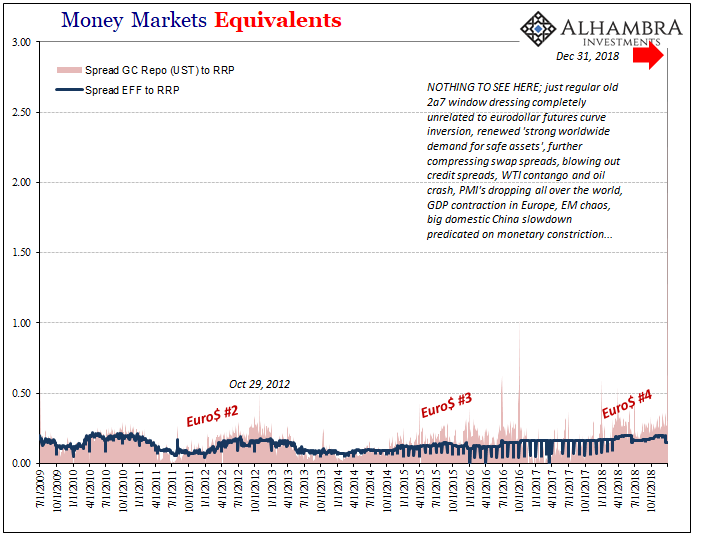

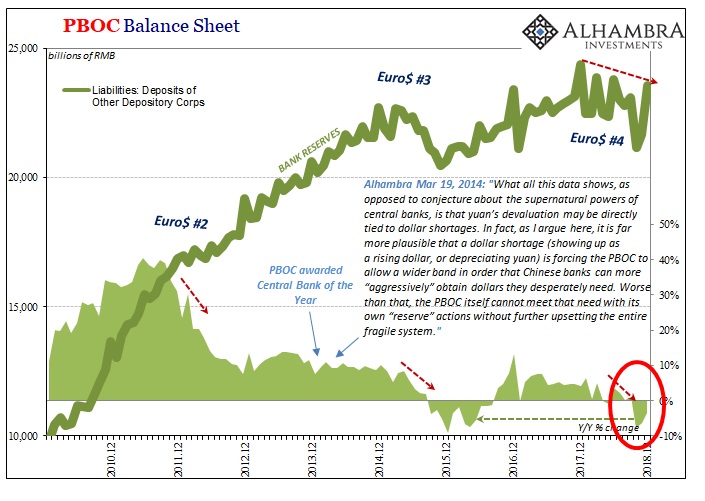

The reason is simple; banks know what central banks don’t. The monetary system globally remains hugely risky even after eleven years and so many central bank attempts I’ve lost count (they are on QE 24 just in Japan, for instance). Liquidity preferences rule every consideration because financial institutions know from recent experience what matters is being able to survive when one of these monetary events strikes – because it always does.

Even at its best in 2017, no one was really buying the boom schtick. The media ate it up actively cheering for technocratic competence to be proven, wanting and needing it to be true. Europe’s economy, like Japan’s and America’s, was doomed (eurodollar system) from the beginning and the bond market knew it.

Now comes the data to demonstrate once again they really don’t know what they are doing. It starts in market doubt that becomes validated by more and more economic statistics.

According to IHS Markit, France’s composite PMI (which includes both manufacturing and services industries) for January was 48.7, well below the 50 dividing line supposedly marking the difference between growth and contraction. That’s just the Yellow Vests, some will say; only they are reversing cause and effect.

French protests sure don’t explain Germany, the composite PMI in France’s neighbor was up slightly to 52.1, being held down by the manufacturing sector. Markit’s index for that segment dropped below 50 for the first time in 50 months.

As a result, the composite for all Europe came in under 51.0 for the first time in five and a half years. The last time the index was at or near 50.7 as it is in January 2019 was the last time Europe was coming out of full-scale recession.

This trend isn’t contained within European misfortunes. I particularly liked the bluntness, for once, with which Markit’s commentary spoke of Japan’s manufacturing sector.

Flash Japan Manufacturing PMI® falls to 50.0 in January (52.6 – December), ending longest expansionary run for over a decade… Production scaled back for first time since July 2016, while confidence lowest in over six years.

The US composite ticked up slightly, registering 54.5 in January up from 54.4 in December. That may seem to indicate US strength or the American economy as the cleanest dirty shirt. There is no decoupling, however, only variances in time before the global downturn strikes everywhere.

We already know what’s going on in China.

The inverted UST curve and eurodollar futures, like Germany’s 10s, suggest the matter has been settled. Sour, not soar. Central bankers will be surprised and shocked if only because more than anyone they fooled themselves with their third-rate magic trick. Recovery is only possible once the media and the public stop buying tickets to see it.

Here we go again. Eurodollar #4 turning into Worldwide Downturn #4.

Disclosure: This material has been distributed for informational purposes only. It is the opinion of the author and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any ...

more