The Geopolitics Of Cheap Energy

Oil prices have fallen again: they are now at $29 a barrel for West Texas Intermediate crude and a similar price for Brent, their lowest since 2003. Natural gas, coal, and other commodity prices have also been dropping of late, in most cases. So: what will be the geopolitical consequences of cheap energy in general and of cheap oil in particular, all other things being theoretically held equal?

One geopolitical consequence of cheap energy is the weakening, possibly, of four potential great powers: Russia, Brazil, China, and Mexico. While the media has understood the Russian and Brazilian half of this list - their economies are both estimated to have shrunk by 1-3 percent druring 2015, after all, which is difficult to miss - it has largely failed to register the Chinese and Mexican half. This is because it views China as being a leading oil, energy, and natural resource importer rather than as a resource exporter like Russia or Brazil, and because it views Mexico as merely a source of drugs, migrants, resorts, and cheap goods rather than as a potential great power.

China

China may be the world’s largest energy importer, but it is has also become its second largest energy producer, and as such only relies on energy imports for an estimated 15% of its total energy consumption, in contrast to 94% in Japan, 83% in South Korea, 33% in India, 40% in Thailand, and 43% in the Philippines. In 2014 imports of oil were equal in value to just around 2.4 % of China’s GDP, according to the Wall Street Journal, compared to 3.6% in Japan, 6.9% in Korea, 5.3% in India, 5.4% in Thailand, 4% in the Philippines, and 3.3% in Indonesia. South Korea and Japan also imported more than two and four times more liquified natural gas, respectively - the prices of which tend to track oil prices more closely than conventional natural gas prices do - than China did. China’s LNG imports barely even surpassed India’s or Taiwan’s. China’s imports of natural gas in general, meanwhile, were less than half as large as Japan’s and only around 20% percent greater than South Korea’s.

China, furthermore, tends to import energy from the most commercially uncompetitive, politically fragile, or American-hated oil-exporting states, such as Venezuela, Iran, Russia, Iraq, Angola, and other African states like Congo and South Sudan. In contrast, Japan and South Korea get their crude from places that will, perhaps, be better at weathering today’s low prices, namely from Kuwait, Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia. Similarly, China gets much of its natural gas from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Myanmar, whereas Japan imports gas from Australia and Qatar and South Korea imports gas from Qatar and Indonesia. China’s top source for imports of high-grade anthracite coal, and its third largest source for imports of coal in general, is North Korea. China has, in addition, invested capital all over the world in areas hurt by falling energy and other commodity prices, including in South America, Africa, Central Asia, Canada, and the Pacific.

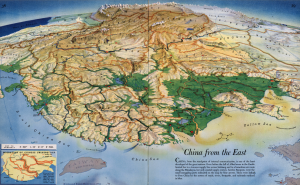

Another mistake the media makes is looking at China as if it were a country, rather than what it really is: both a country and a continent. Continents have internal, deeply-rooted regional divisions, and China is no exception. Its main divide is between areas south of the Yangtze River, which tend to be highly mountainous, sub-tropical, and dependent upon importing fossil fuels, and areas north of the Yangtze, which tend to be flat, more temperate, and rich in fossil fuels.

Northern China, stretching over 1000 km from Beijing southward to Shanghai on the Yangtze, is the country’s political heartland. It is densely populated and home to most of China’s natively Mandarin-speaking, ethnically-Han citizens. When compared to southern China, the north has historically been somewhat insulated from foreigners like the Europeans, Americans and even Japanese. Beijing’s nearest port is roughly 5000 km away from Singapore and the Strait of Malacca; Hong Kong, in contrast, is only around 2500 km from Singapore and Malacca. Beijing is rougly 2600 km from Tokyo by ship, whereas Shanghai is just 1900 km from Tokyo and Taipei is just 2100 km from Tokyo. Japan’s Ryukyu island chain and the Kuroshio ocean currents historically allowed for easy transport from Japan to Taiwan and the rest of China’s southeastern coast; the Japanese controlled Taiwan for more than three and a half decades before they first ventured into other areas of China in a serious way during the 1930s. Even today, Japan accounts for a larger share of Taiwan’s imports of goods than do either China or the United States.

Southern China has often depended on foreign trade, since much of its population lives in areas that are sandwiched narrowly between Pacific harbours on one side and coastal subtropical mountain ranges on the other. In northern and central China, in contrast, most people live in interior areas rather than directly the along the Pacific coast. These people in the interior generally did not engage in as much foreign trade, as in the past moving goods between the interior and coast was often limited by the fact that northern China’s chief river, the Huang-he, was generally unnavigable and prone to flooding northern China’s flat river plains, destroying or damaging roads and bridges in the process. In southern and central China, by comparison, even people living far inland could engage with the coast by way of the commercially navigable Yangtze and Pearl Rivers, which meet the Pacific at the points where Shanghai and Hong Kong are located.

Northern China, however, was most directly exposed to the land-based Mongol and Manchu invaders who ruled over the Chinese for most of the past half-millenium or so prior to the overthrow of the Manchu Qing Emperor in 1912. Today the north continues to retain the political capital, Beijing, and a disproportionally large majority of Chinese leaders were born in north China — including Beijing-born Xi Jinping and Shandong-born Wang Qishan — in spite of the fact that many of the Chinese political revolutionaries, including Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Sun Yat Sen, Zhang Guotao, Chang Kai-Shek, and famed writer Lu Xun, hailed from southern or south-central China.

Today, out of China’s seven Standing Comittee top leaders, only seventh-ranked Zhang Gaoli was born in southern China, whereas five of the seven were born in northern China and one, Premier Li Keqiang, was born in central China. Zhang Gaoli may in fact be the first person born outside of northern or central China in thirty years to have made it to the Standing Committee. He is also the only person currently in the 25-member Politburo born outside of northern or central China. Among the 11-man Central Military Commission, meanwhile, seven were born in northern China, while two were born in north-central China and two in south-central China. Out of the 205 active members of the Party Central Committee, fewer than 15 were born south of central China.

Indeed, the southern half of China, stetching from islands in Taiwan, Hainan, Hong Kong, Xiamen, and Macau in the east to the plateaus of Yunnan, Sichuan, and Tibet in the west, is politically peripheral. It is home to a majority of China’s 120 million or so non-Han citizens (most of whom are not Tibetan or Uyghur, though those two groups recieve almost all of the West’s attention), China’s 200-400 million speakers of languages other than Mandarin, China’s tens of millions of speakers of dialects of Mandarin that are relatively dissimilar to the Beijing-based standardized version of Madarin, most of China’s 50-100 million recent adopters of Christianity, and most of China’s millions of family members of the enormous worldwide Chinese diaspora.

Southern China is physically closer to Southeast Asia (a region with a huge Chinese minority population) and most of the populous areas of Japan, and further away from sparsely populated Mongolia or Siberia, than northern China is. The south’s Fujian province, in particular, is linguistically and economically close to Taiwan, while the south’s Guangdong province is close to Hong Kong. A large share of China’s GDP comes from the coastal areas of China from around Shanghai south to Guangdong, particularly if you include Taiwan as part of the country. Guangdong alone accounts for an estimated 10% of mainland China’s GDP and over 25% of its exports. This creates a somewhat unbalanced dynamic: China’s political periphery is also its economic centre.

As it happens, northern China’s produces almost all of China’s fossil fuels (particulary in and around Shanxi province, 300 km or so inland from Beijing, where a large share of China’s coal is mined), whereas southern and central China, especially if you include the neighbouring economy of Taiwan as being part of China, account for most of China’s imports of energy. Taiwan, in fact, may be more dependent on oil imports than any other significant economy in the world. Falling energy prices may weaken the Chinese political heartland relative to its periphery, in that case. Whether or not this will generate any political instability going forward remains to be seen.

If (a big if) energy prices remain low for a sustained period, then the question of China’s future dependence on imported energy also becomes relevant, as does the question of the future dependence on imported energy of China’s most important neighbours. In that case, how dependent on energy imports will countries like China, Japan, and India be in a decade or two from now?

While it is impossible to know what the future will be like, it is not difficult to imagine that China will remain less dependent on energy imports than India and/or Japan during the years or decades ahead, as a result of India’s still-emerging economy and Japan’s still-roboticizing economy.

China is not likely to be a major adopter of energy-intensive robots, in per capita terms, because China has a far larger cheap labour force than any country in the world apart from India. Japan, in contrast, will likely help lead the robot revolution, as its labour force is expensive and aging rapidly. This could make Japan even more dependent on importing energy, as machines that are both highly mobile and capable of sophisticated computation require an enormous amount of energy to run — and indeed, one of their main advantages over human labour is that they can and frequently will be tasked to run 24-7, without even taking any time off for holidays or sick days.

China is not certain to increase its energy imports nearly as much as less-developed economies like India, meanwhile, as the Chinese inudstrial sector is facing challenges as a result of its past generation of energy-intensive growth. China faces rising labour costs in its cities, a pollution problem, crowded transportation infrastructure, a US that is concerned with Chinese industrial power, and countries throughout the world afraid of China’s world-leading carbon emissions. In addition, China is located much further away from the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea oil and gas fields than the Indians and other South Asians are, and so might have difficulty accessing them in a pinch.

China may also have to face industrial competition from resource-rich or capital-rich economies such as Australia, Norway, Canada, Qatar, Texas, and maybe even Hong Kong, which will perhaps be able to use energy-intensive robots of various kinds to build up their manufacturing sectors in spite of their small labour forces. This could make China’s industrial growth rate slip, which in turn might reduce China’s resource imports and thus prevent China from becoming the leading beneficiary of low energy and commodity prices.

Such a shift will be especially likely if the United States or European economies decide to enact tariffs on goods coming from places that generate power by using coal in inefficient ways, a prospect that has become increasingly likely as a result of America’s triple-alliance between environmentalists opposed to coal consumption, shale gas producers competing with coal, and energy companies trying to pioneer more expensive but cleaner ways of consuming coal. China may then have to focus on growing its service sectors instead of its energy-intensive industrial sectors.

Japan, lastly, might benefit from Russia’s energy-related woes more than China will. This is not only because the Chinese have to a certain extent often looked to Russia as an ally against the West, but also because the areas of Russia that China is close to are mostly irrelevant to China:

they are landlocked, Siberian, and for the most part located far from China’s population centres. Pacific Russia, in contrast, located next to the Sea of Japan on the East Asian side of Russia’s Pacific mountain ranges, has a far more liveable climate than the continental Siberian interior, is home to a number of useful medium-sized port cities, and accounts for much of the oil and nearly all of the Russian natural gas exports to Asia — led by energy-rich Sakhalin Island, which is just 40 km away from Japan and was partly owned and inhabited by the Japanese prior to the Second World War.

Russia is, in fact, may even better prepared to fight another border war with China like it did in 1969, which might not be too different than the many other wars Russia has fought around its borders both prior to and since then, than it would be to face off against Japan again within its far-eastern, mountainous, archipelagic and peninsular Pacific region, as it did both in 1905 and during World War Two. Of course this does not mean Japan will attack Russia — though it has certainly toyed with the idea of making more forceful moves in the Southern Kuril Islands, which both countries claim as their own. Even the unspoken possibility of conflict, however, may help grant the Japanese leverage over Russia in negotiations relating to commercial or political issues.

Mexico

Mexico is much more than just America’s messy basement. It has the world’s 11th largest population,14th largest GDP, and, because it is in the New World, its population is in many ways much more internally unified than those of most other large countries are. It also has important ties to the rest of the Spanish-speaking world, to the Latin-based world in general, and to the 35 million or so Mexicans in the United States in particular, most of whom live in states adjacent to the Mexican border. Mexico is the clear potential leader in the Spanish-speaking world: its population is bigger than those of Colombia, Argentina, and Venezuela combined, and its economy is about to surpass Spain’s. If you include illegal transactions, Mexico already has the largest economy in the Spanish world by far. Along with (or perhaps instead of) Portuguese-speaking Brazil, Mexico could potentially help Latin America to become one of the most prominent regions in the world during the decades ahead.

Mexico may not be a major beneficiary of low energy prices, for three general reasons. First, it is a net oil-exporting economy: oil exports accounted for an estimated 2.7% of Mexico’s GDP in 2014, and Mexico had been hoping to increase its oil and gas production since Mexico’s President enacted widely-touted reforms in the country’s energy sector in 2014. Mexico is also often a relatively high-cost oil producer, and so may be forced to cede market share to more price-competitive producers in other countries.

Mexico has admitedly been benefiting from cheap gas prices brought on by Texas’s shale boom. Mexican imports of US gas have nearly tripled since 2009, which has benefited the industrial sector in northern and north-central Mexico. This gas import growth might slow going forward, however, as America’s LNG export facilities may soon be coming online, LNG import facilities in both Europe and China are expected to be opened soon, and the Panama Canal expansion which will be finised this year may allow LNG ships to traverse the canal from Texas to Asia for the first time. As LNG allows US gas to be sold worldwide, Mexico’s import growth of US gas might slow down. In any event, Mexico is the 19th largest natural gas producer in the world, so even with increasing imports from the US it will not soon become a significant net importer of natural gas.

Second, Mexico’s has ties - both existing ties and potential future ties - to other countries in Latin America, a region that is highly economically dependent on exports of energy and other natural resources. Most of the South American economy is already in or flirting closely with recession as a result of the commodity crash, which on the whole is probably not a good thing for Mexico.

Third, Mexico has ties to the southwestern United States, in the areas of America that were part of Mexico prior to the 1830s-1850s, most notably California and Texas where around 25 million Hispanic-Americans live today. Like Mexico itself, this part of the US is dependent on energy exports, led by Texas (a major producer of oil, gas, coal, wind power, solar power, and refined petroleum products: Texas produces approximately one-fifth of US energy and one-third of US crude oil) but also including the surrounding energy-producing states of Oklahoma, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Louisiana, Arkansas and the federally-administered oil-and-gas producing waters in the Gulf of Mexico. Nearly all of the states with a high share of Mexican-Americans are either energy-exporting states or else, in the case of California, New York, Florida, and Arizona, have the lowest per capita energy consumption apart from any states other than Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.

Even California’s energy imports do not balance out Texas’s energy exports, because California is itself the US’s third largest oil-producing state, tenth largest energy-producing state, and has the fourth lowest per capita energy consumption; its energy imports are not as large as one might expect given the enormous size of the Californian economy. They might even shrink in the future, if the Monterrey basin shale resources are developed. California is also the largest agricultural producer in the United States (Texas is fourth), a big sector that can be hit by falling commodity prices as well.

In the future, meanwhile, somewhat similar to China, Mexico’s industrial growth may not be as strong as most people expect, which could cause it to become less dependent on energy and other commodity imports relative to other countries. Mexico is currently a major industrial economy, the result of its large and cheap labour force and proximity to US consumers. As labour and other prices in northern and to a lesser extent central Mexico are becoming more expensive due to economic growth in these areas, however, Mexico’s industrial growth rate may slow.Tthis is because central and especially southern Mexico are separated from the US by vast areas of mountainous deserts or jungles, making the north-south roads and pipelines through Mexico expensive to build, use, and maintain, as well as potentially vulnerable to groups like the drug cartels, indigenous peoples, or local governments. Southern Mexico resembles Central America more than it resembles northern Mexico.

Mexico may increasingly also have to face industrial competition from Cuba, which is the only other sizeable Hispanic country close to the United States; from Venezuela, if it too can finally mend fences with America and leverage its energy resources to industrialize; or from Canada and the US, if they try to use robots and other technologies to re-industrialize. If, finally, domestic politics lead the US to try to make the Mexican border more of a barrier, Mexico might have to industrialize less and stick more to the many other sectors of the diverse Mexican economy, which are less resource-intensive.

Europe

There is a fourfold division in Europe, where energy and commodity imports are concerned. First is between mainland Europe, which is a major importer of energy and oil, and the regions surrounding mainland Europe (namely Scandinavia, the North Sea, the former Soviet Union, the Middle East, North Africa, western Africa, and the Americas), which are energy and commodity producers. Even the United States has now become such a big energy producer that its energy imports account for only around 15% of its overall energy consumption, a very low share in comparison to an estimated 62% in Germany, 71% in Spain, 77% in Italy, 46% in France, and 43% in Britain.

Second is between countries which use the Euro as their currency - Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Greece, Slovakia, etc. - which tend to be significant importers of oil or other commodites, and countries that do not use the Euro - Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Britain, Denmark, Poland, Romania, Czech Republic, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, etc. - which tend to produce a decent amount of oil, energy, or other commodities — or else, like Switzerland, have economies that are not energy-intensive and so may not benefit as much from cheap energy. (Switzerland, the 20th largest economy in the world, also relies on imports for just 52% of its energy, according to the World Bank, which is a lower share than in all but four of the 19 countries within the Eurozone). Admitedly there are a few exceptions to this rule: most notably Turkey, which imports a lot of energy but does not use the Euro, and Estonia and to a lesser extent the Netherlands, which produce a decent amount of energy domestically yet do use the Euro. Still, even the Netherlands is a major net importer of crude oil.

The third division is between countries that are in the European Union and European countries that are not in the European Union. This division is similar to the Eurozone one, except that states like Britain, Denmark, Poland, Romania, and Sweden — all of which are mid-sized energy or commodity producers - are in the European Union but do not use the Euro, which leave the continent’s major commodity and enegy producers of Norway, Russia, and Ukraine as more prominent outsiders. Turkey, meanwhile, is, unlike Russia, Switzerland, Norway, or Ukraine, a member of the quite important European Customs Union, though like them it is not part of the EU.

Finally, and in some ways most pertinently, there is a division between northern Europe and southern Europe. The further north you go, the less dependent the Europeans are on energy imports. Scandinavia and Russia are the furthest north: they are major energy and commodity producers. (Even the three Baltic states, which are generally assumed to be among the smaller countries in Europe, actually own far more land per capita - and especially forested land, which is crucial for feeding Europe’s sizeable wood-fuel industry - than any European countries to the south of them do).

These are followed by countries like Britain, the Netherlands, Romania, Ireland, the German economies, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Belgium, and northern France, which have economies that are also not too dependent on energy imports. (Like Switzerland, both Ireland and northern France have economies that are not at all energy-intensive, when compared to others).

In southern Europe, finally, there are the economies of Spain, Portugal, Greece, Italy, France-sans-Paris, Turkey, Cyprus, and Malta, which are highly dependent on imports of oil, natural gas, and energy in general. (While nearby Algeria remains a large energy-exporting state and Libya has energy-export potential, Morocco, Israel, Lebanon, and Jordan are highly dependent on energy imports and Egypt and Tunisia are both more or less energy neutral). Perhaps not incidentally, most of southern Europe has experienced an economic depression during the past eight years.

The biggest exception within southern Europe, meanwhile, is Italy, which produces more oil than France, Greece, Turkey, and Spain combined, slightly more oil than even Germany produces. This may in fact partly help to explain why Italy has been suffering a great deal of late, whereas the Spanish, Portuguese, and possibly even Greek economies might finally be on the mend. Even Italy is the world’s third largest gas importer, however, so as with Spain, Portugal, Turkey, and Greece, the Italians depend on imports from abroad to supply more than 70% of the energy they consume.

Turkey

Turkey is in the most interesting position of all when it comes to energy and geopolitics. It, along with its nearest European neighbours Greece, are significant net energy importers; Turkey has a relatively energy-intensive economy and energy imports account for three-quarters of its energy consumption, while in Greece energy imports account for 60% of energy consumption. Oil imports in Turkey and Greece were estimated to be equal in value to 3.2% and 4.5% percent of GDP in 2014, respectively, both figures quite a bit higher than in most other countries within Europe.

Surrounding Turkey and Greece, however, is a ring of leading energy-producing regions: the Middle East, Russia, Ukraine, the Caspian Sea-Central Asia region, and North Africa. Even Turkey’s closest Western neighbours of note, namely Italy, Romania, and Austria, are not necessarily going to benefit much from cheap oil or cheap energy. Italy produces nearly three times as much oil as Turkey does, Romania produces nearly twice as much oil as Turkey and depends on energy imports for just 22% of its energy consumption, and Austria has the lowest oil-imports-as-a-percent-of-GDP of any country in the Eurozone. Even Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt have made major new energy discoveries of late, of natural gas within the Eastern Mediterranean.

In past years, Turkey has already seen many of its neighbours fall to shambles to one extent or another — first the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Lebanon, Algeria, and the Caucuses in the 1990s, now Iraq, Syria, Ukraine, Greece, Georgia, and Libya, among others. Further troubles in the regions surrounding Turkey, then, perhaps brought on by the falling price of energy, could create a serious power vaccum for the Turks to consider filling.

Turkey’s close-to-home rivals the Kurds, meanwhile, are also potential losers in a cheap energy environment: they produce a lot of oil in Iraqi Kurdistan, abut a number of hydropower facilities located within Turkey’s mountainous Kurdish regions where the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers form, and possess ties in some cases to energy-rich Iran (as a result of the Kurdish population in Iran as well as the fact that Persians tend to be ethno-linguistically closer to most Kurdish groups than most Kurds are to either Turks or Arabs) or to energy-rich Iraq (as a result of the sizeable Kurdish population that lives in Iraq).

India

India, like China, is both a major energy producer, the seventh largest in the world, and a major energy consumer, the third largest in the world. In India, however, oil imports were equal to 5.3% of GDP in 2014, compared to just 2.4% in China, while energy imports accounted for 33% of Indian energy consumption, compared to just 15% for China. And whereas in China the areas that benefit the most from cheap energy are located outside of the Chinese political heartland, in India the country’s political core territories — which are centred around India’s largest state by far, namely Uttar Pradesh (population 200 million), as well as parts of its neighbouring states like Bihar (India’s third most largest state), Madhya Pradesh (5th largest), Rajasthan (7th largest), and Delhi (India’s capital city, population 17 million) — may benefit among the most in India from falling oil and energy prices. Some of the other areas within India, on the other hand, such as parts of both Western India (which produces 75% of the oil produced onshore in India, and which has economic ties to the nearby energy-rich Persian Gulf) and Eastern India (which is where most India’s coal and other commodities are produced), might not benefit in the same way.

India’s geopolitical dream is of a prosperous, peaceful Indian Ocean basin in which it, by virtue of its size, diversity, and central location, would be far and away the most prominent and powerful country. In order to accomplish this India must have better relations with Pakistan, a country that has been backed by the United States as well as by fellow Muslim states like Saudi Arabia. With the Saudis and other Sunni Muslim countries hurt by cheap oil and energy prices, and with India’s traditional allies against Pakistan, namely the Russians and Iranians, hurt by cheap energy too, both India and Pakistan might perhaps be forced to rely more heavily on the Americans. If, then, the Americans decide to prioritize Indian-Pakistan peace-making as a way to maintain stability in South Asia and help to contain forces like China, Russia, and pan-Islamism, there may be some cause to be hopeful. Don't be too sure though: there are plenty of reasons why India, Pakistan, and the United States might each find it difficult to pursue Indian-Pakistani or Hindu-Muslim reconciliation.

Within the wider Indian Ocean region, stretching 6000 km from Madagascar to Indonesia and 6000 km from Sri Lanka to Kerguelen, there is also some scope for careful optimism. In East Africa, from around Ethiopia south through the Great Lakes, most economies are not dependent on energy exports in the way that western African countries like Angola, Nigeria, Algeria, Congo, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea are. Even South Africa, the world’s sixth largest coal exporter, is not nearly as dependent on energy exports as Nigeria, Angola, or Algeria are, and is a net importer of crude oil. Oman and Yemen, similarly, the two Arab countries with coastlines directly along the Indian Ocean, are not nearly as dependent on energy exports as other Arab countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Kuwait are. They, especially Yemen, may also be leading importers of food.

In the eastern Indian Ocean, the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and especially Java (combined population: 195 million) tend to be energy-importing areas, in contrast to Indonesia’s Pacific islands like Kalimantan and - 3500 km to the east of the Indian Ocean - West Papua, which account for most of Indonesia’s energy-production as Sumatra’s aging oil fields are declining. In Indonesia’s neighbour Malaysia, similarly, most oil production comes from around the Pacific Island of Borneo, an island Malaysia shares with Indonesia (and Brunei), rather than from the Malay Peninsula on the edge of the Indian Ocean where most of Malaysia’s population lives. Singapore, moreover, which is located roughly in between western Malaysia and western Indonesia, is the world’s 13th or 14th largest oil importer (it is roughly tied with Thailand, which is also located along the outer edge of the Indian Ocean); in spite of its small size Singapore now imports nearly twice as much crude oil as Indonesia and Malaysia combined export to the world.

Disclosure: None.