The Canadian Housing Market Enters A Transitional Phase

A cornerstone of the Bank of Canada’s work is the assessment of the main risks to financial stability. The Bank regularly analyzes the resilience of the Canadian financial system to shocks; it takes a close look at interaction between household debt and housing prices and the efforts of the government to mitigate those risks. The Canadian housing market continues to be one area that the Bank has singled out as a risk to the financial system in the recent past. Its Financial System Review (FSR), issued this week, reveals that the housing industry has entered a new phase, one in which mortgage demand and housing prices have slowed dramatically and are in transition towards a more balanced market.

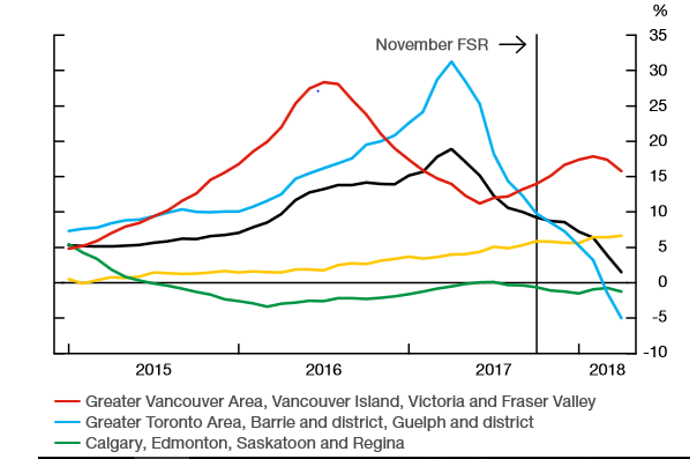

Figure 1 traces the annual increases in house price in the major cities in Canada. The acceleration in housing prices in The Greater Vancouver Area (GVA) peaked in 2016 and in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) in 2017. While the nation, as a whole, and the GTA and GVA in particular, are experiencing growth in household formations, the big change in housing demand originates in the new rules affecting the Canadian mortgage industry.

Figure 1 Canadian Housing Prices Have Peaked

Source: Bank of Canada, FSR, June 2018

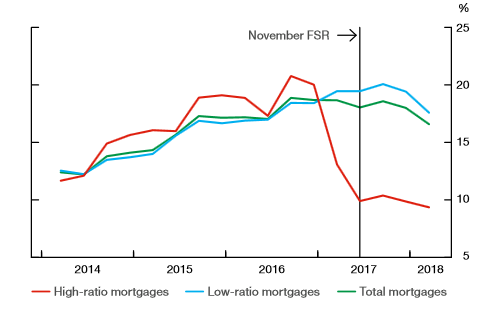

In 2016-17 the Federal government introduced a series of mortgage rules that have altered the landscape of home buying. Tightened mortgage underwriting standards have reduced the maximum size of loans that borrowers can obtain at a given level of income. Changes to mortgage insurance rules made all high-ratio mortgages (those with a loan-to-value ratio above 80 per cent) subject to a mortgage interest rate stress test. This requirement cut in half the proportion of new high-ratio borrowers who take on mortgage debt in excess of 450 per cent of their gross income (Figure 2). Overall, the share of these highly indebted households in new mortgage lending stopped rising and began their descent in late 2017. The 2016 and 2018 regulatory changes have also led to a reduction in the proportion of new low-ratio mortgages. The upshot of all these changes has been both negative with respect to curbing credit growth and positive with respect to improving the quality of new mortgage lending as buyers are required to provide more equity towards their purchases. One side effect of these changes has been the growth of less-regulated private mortgage lenders, such as mortgage investment companies. In the GTA, private lending now accounts for 8 per cent of new mortgages, since many borrowers, who are turned down by the commercial banks, are forced to seek out alternative lenders.

Figure 2 Mortgage Lending Ratios

Source: Bank of Canada, FSR, June 2018

From a macroprudential viewpoint, the combination of slower growth in home prices and improved quality of mortgage lending should go a long way to strengthening financial stability. It now appears that the housing market is engineered for a soft landing which, if maintained, will ease the industry into a more balanced situation.

As long as there are shadow banks, it is business as usual. If they falter, we know what could happen by looking at the USA last decade.

Canada has a very small shadow bank---only about 10% of the mortgage market. The big six banks own 75% of all mortgages ( the balance is held by regulated credit unions, second tier banks).