The Bank Of Canada Engineers A Recession By Curtailing Credit

The one sure-fire way to engineer a slow down is to restrict credit expansion, and that is precisely what the Bank of Canada is doing. While interest rates are one major sign of credit conditions, a far more important measure concerns the availability of credit to businesses and households. Credit conditions can be measured from both the personal and business loan side of a bank’s ledger. But first, we need to look at the total expansion of credit, best measured in terms of the growth in the money supply.

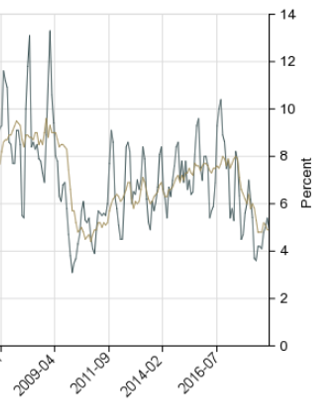

A conventional measure of the money supply is M 2, -----cash in circulation, demand and savings deposits and money market mutual funds (Figure 1). Money supply growth has dropped significantly starting in 2017 and continuing to this day. Beginning in 2009 the growth rate accelerated from about 5% annually, reaching a recent high of just over 10% annually in 2017. Since then, the rate of growth has slowed and is now approaching the low rate that existed as we came out of the 2008 financial crisis. When the money supply grows at 5% yearly this indicates that nominal output---- real growth plus inflation--- will not exceed 5%. M2 is a broad measure, so we need to examine different types of loans to see how credit has been restricted.

Figure 1 Money Supply Growth- M2

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Bank of Canada

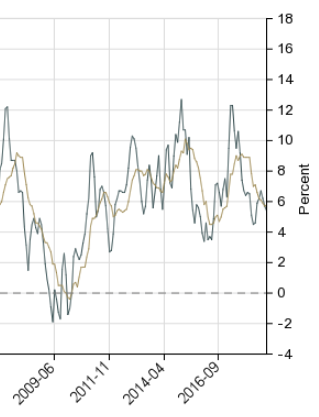

The growth in business credit has basically mirrored the slow down in money supply (Figure 2). Surveys by the Bank of Canada reveal that approval rates for new loans were down in 2018 Q4, citing an unwillingness on the part of banks to underwrite deals because of concerns over collateral and general economic conditions. Granted, the corporate sector can turn to the bond market for financing, the commercial banks continue to play a major role in providing funding for business expansion.

Figure 2 Business Loan Growth

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Bank of Canada

The most dramatic downward adjustment has been in the residential mortgage market. Mortgage growth in Canada rose by a mere 3 % in 2018, the slowest pace in 17 years, and half the growth rate from two years ago. Surveys by the Bank of Canada cited higher interest rates as the main reason for the fall-off in demand. Commercial banks, which provide 75% of all mortgages, have, as a matter of commercial policy, pulled in their horns. At the same time, the Federal government introduced a series of mortgage stress tests resulting in fewer clients qualifying for new mortgages. The impact of these credit restrictions was almost immediate as home prices started to decline and house construction activity dropped sharply.

Since the Canadian bond yields tumbled in recent weeks, we can expect lower mortgage rates contribute to some pick up in household credit over time. However, it is an entirely different matter whether lenders will actually advance credit, even as rates fall. The great monetarist, Milton Friedman, argued, counter-intuitively, that low interest rates can be a sign of a tight financial market. Low rates signify weak economic growth and bankers are reluctant to advance credit in recessionary times, regardless of the prevailing interest rates.

So, the question, prof, is whether this will turn into a soft landing or hard landing. Maybe Canada has more success than the USA, I don't know.

We have lots of safety nets such as universal health care that can soften the blow.My sense is that housing will hold well because we are accepting 400k immigrants who need housing in 2019.