Some Thoughts On European Monetary Policy

In America, it’s not easy to figure out exactly what’s going on with monetary policy. Europe is even more opaque. Indeed we still don’t know the third quarter figures for Eurozone NGDP, and won’t find them out for months. Nonetheless, I’ll take a stab at the question, as well as a few observations on the UK.

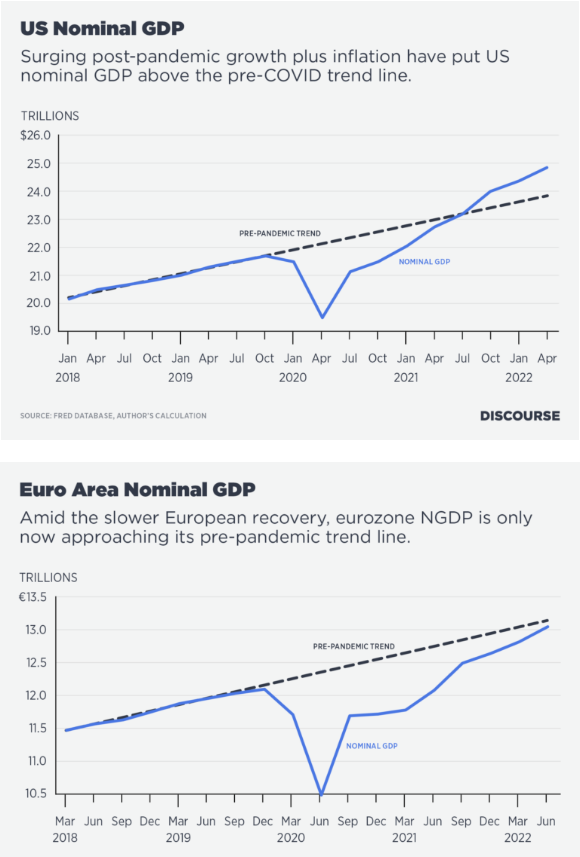

David Beckworth has an excellent Discourse article on inflation, which contains these graphs:

At first glance, it look like the US economy has overheated and the Eurozone economy is back on track. The US is quite overheated, but the Eurozone picture is a bit more complicated, for several reasons:

1. The Eurozone NGDP data is quite dated, and (AFAIK) recent NGDP growth has been quite high.

2. The pre-pandemic trend is not necessarily the optimal policy path. Suppose the Fed favored a NGDP growth target of 2% plus trend RGDP growth (a reasonable idea.) And suppose they noticed that America’s RGDP rose at an annual rate of 2.25% between 2009:Q4 and 2019:Q4. They then decided to target NGDP growth at 4.25%. Unfortunately, that policy would not succeed in the Fed’s objective of ensuring 2% long run inflation, as they’ve overestimated trend growth. The unemployment rate was 10% in late 2009, and fell to 3.5% in late 2019. They would have estimated trend growth over the expansion phase of the cycle, not the entire cycle. The actual trend RGDP growth rate in America is now about 1.5%, and lower still in Europe and Japan.

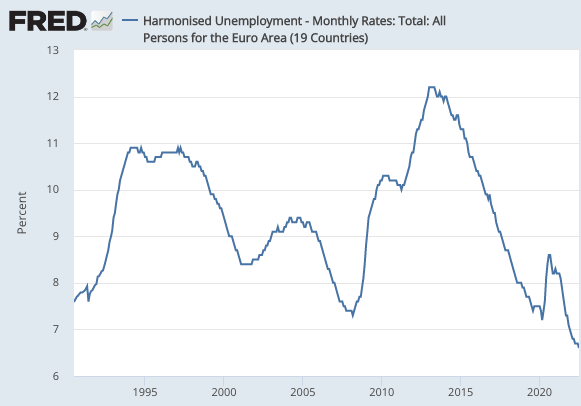

Notice that Eurozone unemployment had been falling rapidly prior to Covid, reaching a record low of 7.2% in March 2020. During the recent recovery, it’s fallen even lower:

So the Eurozone trend RGDP growth rate is also lower then its pre-Covid trend.

When people say something cannot go on forever, they are often wrong. The US trade account deficit can go on forever, or for at least as long as our multinationals earn big profits overseas. But a falling unemployment rate really cannot go on forever. So the trend rate of Eurozone NGDP growth might overstate the optimal rate by at least a little bit.

On the other hand, I see two pieces of evidence pointing the other way, against the view that the Eurozone is overheating:

1. Even if David’s graph incorporates a trend line for NGDP with slightly above average RGDP growth, the Eurozone has also been mostly undershooting its 2% inflation target. So perhaps that trend line is about right.

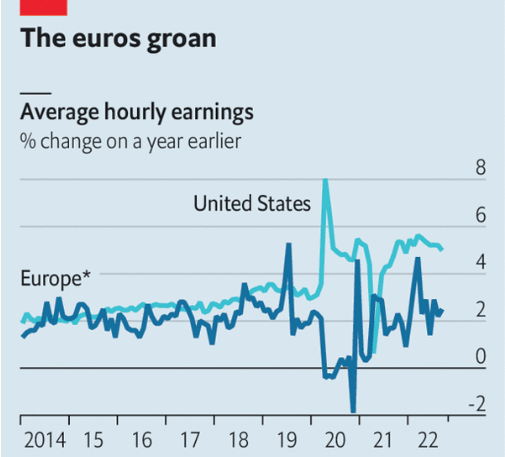

2. There’s little evidence thus far of demand-side overheating in the Eurozone wage date:

On the other, other hand, there are composition effects to consider, as well as lags. The Economist warns us that Eurozone wage inflation may be about to take off:

So far, European pay has increased little. Unlike in America, six in ten workers have collective-bargaining agreements, which tend to run for a year or more—meaning it takes time for economic conditions to influence their pay. Trade-union negotiators have limited demands, aware that a wage-price spiral would come back to haunt them. But negotiators’ patience is beginning to wear thin. Germany’s public-sector unions will enter forthcoming negotiations seeking a raise of 10.5%.

The problem for bosses is that the labour market remains exceptionally tight. The share of firms reporting that staff shortages are limiting their production is near record highs in both the manufacturing and service sectors. One reason is the enormous backlog of orders from the pandemic. Manufacturing firms have on average more than five months of work on their order books, according to a recent survey, up from four before covid struck. Add to that the cohort of workers retiring each year in ageing countries such as Italy and Germany, and a recipe is in place for a tight labour market throughout 2023.

All of this means the peak in inflation is probably some way off.

So I remain agnostic on the wage question. I’m quite willing to accept the view of Eurozone doves that the inflation problem has been almost entirely supply-side up through mid-2022. I’m less sure of the situation now and going forward, and indeed am puzzled as to why the Economist predicts tight Eurozone labor markets in late 2023. I thought all the experts were telling us that a Eurozone recession was inevitable in 2023? The situation remains confusing, at least to me.

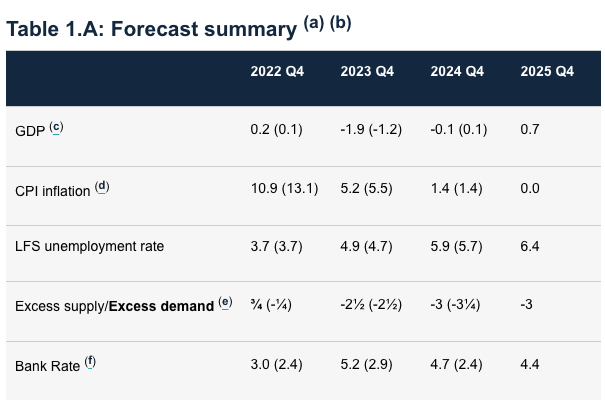

The situation in the UK is equally perplexing. Here’s a table from the BoE:

By adding GDP growth and CPI inflation, we get a very crude estimate of expected NGDP growth, which slows from 11.1% in 2022 to 0.7% in 2025. The average growth rate over that 4-year period (about 4.1%) is relatively high compared to the roughly 3% to 3.5% (post-Brexit) trend NGDP growth required in the long run for the BoE to hit its 2% inflation target. On the other hand, much of the fast growth in 2022 is a recovery from the Covid slump.

The British case raises a number of tricky questions. Is NGDP level targeting even appropriate? If so, where should we draw the trend line? If you look at RGDP growth and unemployment, 2023-24 looks like a recession. So why are forward markets forecasting a Bank Rate of 4.7% in late 2024? I’m genuinely puzzled.

I suspect that over the next few years I’ll revise some of my assumptions about how the macroeconomy works. One casualty might be Okun’s Law, which has performed very poorly in the US during 2022. Another might be my assumption about secular trends in interest rates, TIPS markets, and the Phillips Curve. Right now, US forward markets are forecasting high interest rates in 2023 and 2024. They are also forecasting PCE inflation falling back close to 2%. Larry Summers says that that sort of fall in inflation cannot happen without a recession. His claim seems plausible, but then why are fed futures so high in 2024? Wouldn’t interest rates fall sharply in a recession? And if the answer is that markets don’t trust the Fed to bring inflation down, then why don’t the TIPS spreads reflect this?

Over the next few years, at least one of our major assumptions about how the macroeconomy works is likely to need revision. A few years back, Tyler Cowen spoke of a Great Stagnation. I wonder if the world isn’t about to enter an even greater stagnation. Very low RGDP growth, and yet a surprisingly low unemployment rate. We will see.

More By This Author:

The Doves Were Wrong

Lessons From The Russian Gas Debacle

The Real Problem In Britain